The Our Lady of the Hour Dominican Latin church in Mosul

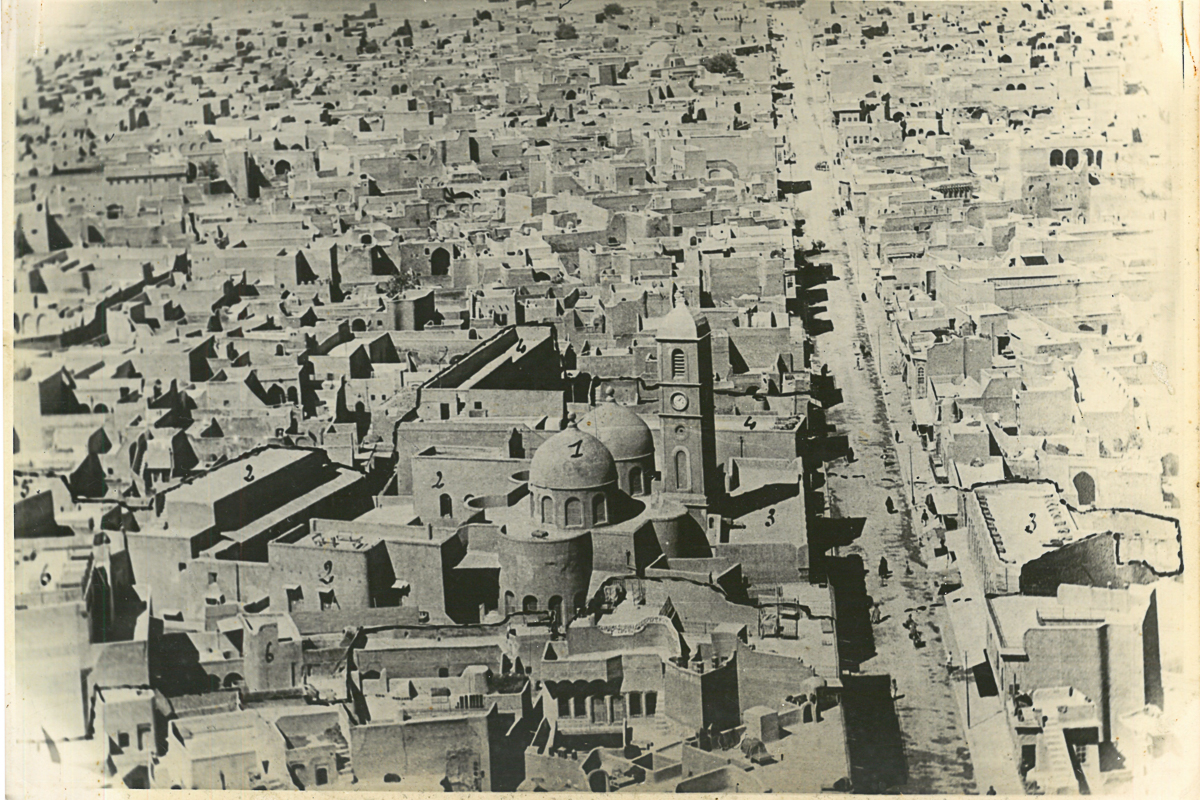

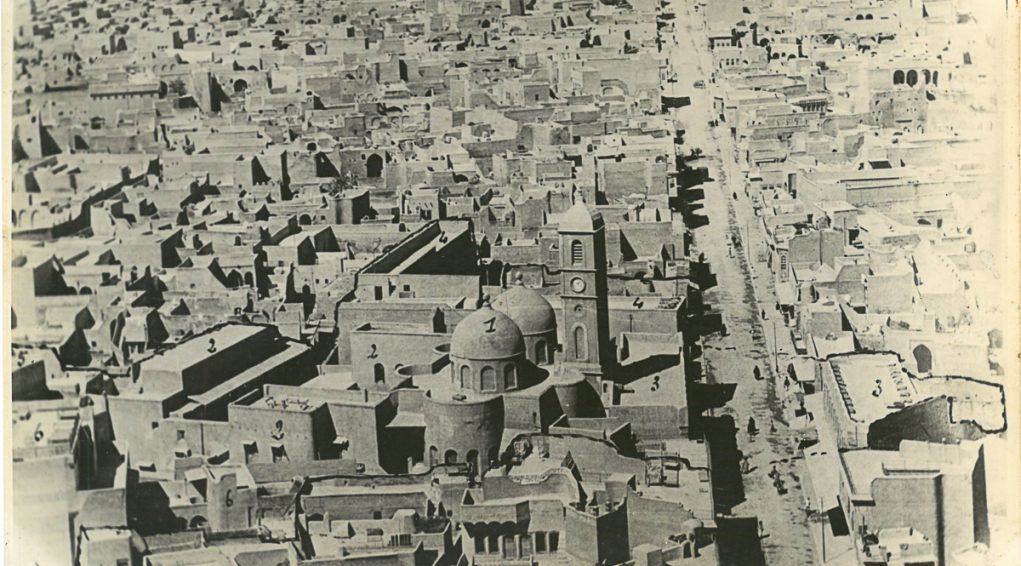

The Our Lady of the Hour Dominican Latin church in Mosul, is located at 36°20’27.19″N 43°7’38.39″E and 230 metres altitude, in the south sector of the old city of Mosul as designated by the Ottoman city walls, at the crossroads between the Al-Farouq and Niniveh roads.

Since 1750, members of theDominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia, have been actors, experts and vital witnesses to the history of Christianity in Iraq and the dangers facing Christians in the Middle-East.

The first Dominican church in Mosul was built by the Italians. This was replaced by the new Latin church built between 1866 and 1873 by the Dominicans of the Province of France. It is an imposing building, both solid and slender, “in the Byzantine style”with a triple nave and five transepts.

The famous clock tour of the church of Our Lady of the Hour is found to the north of the building between two apse chapels. Empress Eugénie de Montijo, wife of Napoleon III, gifted this clock tower, the first in Iraq, in 1876. The clock installed in 1880 was a famous four-dial clock.

The Latin church of Our Lady of the Hour was part of a convent complex restored in the 2000s. The convent was looted and ransacked during the three years Mosul was occupied by the Islamic State group from 2014 – 2017.

Pic : The Our Lady of the Hour Dominican Latin Church in Mosul, ransacked and looted during ISIS’ occupation of Mosul (2014-2017) and damaged during the battle to liberate the city (2017). April 2018 © Pascal Maguesyan / MESOPOTAMIA

Location

The Our Lady of the Hour Dominican Latin church in Mosul, is located at 36°20’27.19″N 43° 7’38.39″E and 230 metres altitude, in the south sector of the old city of Mosul as designated by the Ottoman city walls, at the crossroads between two major roads: the Al-Farouq and Niniveh roads.

Fragments of the Christian history of Mosul

This chapter is largely based on the work of Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux o.p. who lived in Iraq for 14 years from 1968 to 1983 as part of the Dominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia, based in Mosul. See, two books by Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux, in particular: « Va à Ninive ! Un dialogue avec l’Irak », Éditions du Cerf, October 2000; and « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Éditions La Thune, Marseille, July 2015.

_______

Mosul “remains a Christian metropolis,”[1]as attested by its history, and its ancient and modern heritage, which persists despite recent catastrophic events.

Although the first archdiocese is attested to in 554[2], it is also important to take into account the Paleo-Christian apostolic tradition. “Three churches are proud to be founded on houses where apostles are said to have stayed. The Sham’ûn al-Safa’ church, built during the Atabeg period in the 12th – 13th centuries, is said to be built where Saint Peter stayed during his visit to Babylonia and the Mar Theodoros church is connected to the visit of the apostle Bartholomew.As for the apostle Saint Thomas, the house where he was shown hospitality on his journey to India, became a church.”[3]The church in question is the Syriac-Orthodox church Mar Touma described herein.

The first church attested to in Nineveh (modern-day Mosul-East) dates back to the year 570. It is the Mar Isha’ya church which is even mentioned in the “Chronicle of Seert”. This confirms a pre-existing Christian community. In the 7th century the Syriac-Orthodox Mar Touma church was also known of. From the 7th century onwards, the Mar Gabriel monastery was the seat of one of the Church of the East’s most important schools of theology and liturgy. The al-Tāhirā Chaldean church was built on the site of this monastery in the 18th century.[4]

Over the centuries, through successive councils and conflicts, a multitude of churches of different denominations, including the Armenian and Latin churches, were formed.

Of these various fragments of history, the Muslim conquest must be cited as one of the most important. Mosul fell in 641 and the Christian members of its population became dhimmis, with (limited) rights and (stringent) obligations based on their religious identity. This status remained in force up until the 19th century and was abolished in the Ottoman Empire in 1855. Despite this abolition, Christians (and Jews) still remain defined by their dhimmistatus which governs denominational relations in public life and attitudes in almost all Muslim countries. It is still legally enforced (in Iran).

In the 7th and 13th centuries, at the height of the Seljuq period, the Atabeg dynasties imposed their rule throughout Iraqi Mesopotamia and made Mosul a centre of power. At this time, Syriac-Orthodox Christians persecuted in Tikrit fled to the Nineveh plain and Mosul, where they established their community and founded the Mar Ahûdêmmêh (Hûdéni) church. “At the end of the 20th century due to below-ground flooding throughout the neighbourhood, the Mar Hûdéni church located well below ground level was flooded and had to be abandoned”.A new church was built right on top of the old one. Thankfully, the royal door in the Atabeg style, described by Father Fiey as a “jewel of 13th century Christian sculpture”,was transported to the new church and given pride of place. [5]

Following on from the Atabeg, the Mongol Houlagou Khan, took Mosul but spared the city from destruction and from the massacres committed in Baghdad in 1258, thanks to the “cunning governor of the city, Lû’lû’, of Armenian origin.”[6]The following century was nonetheless a tragic one. “Christian persecutions peaked under Tamerlan, whose armies ravaged the Middle East in the first years of the 14th century and exterminated the Christian populations. No other eastern Christian church underwent anything close to this type of eradication, the community in Iraq is well placed to claim the first prize in martyrdom.”[7]

In 1516, Mosul fell into the hands of the Ottoman Turks for the first time, but it was not until the following century that they established a dominant presence in Iraqi Mesopotamia that was to last for four centuries after the conquest of Baghdad in 1638 by the sultan Murad IV.

In the 16th century Mosul was a major centre of Christian influence. It was here that the schism of the Church of the East took place, with the election of Yohannan Sulaqa as the first patriarch of the Chaldean church. Abbot of Rabban Hormizd Monastery in Alqosh, he took the name Yohannan/John VIII and travelled to Rome to profess the Catholic faith. On 20th April 1553 Pope Julius III named him patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic church marking “its official birth.”[8]After Diyarbakır (in the south-east of modern-day Turkey) and before Baghdad (in 1950), the seat of the Chaldean church was established in Mosul in 1830, with the election of Jean VIII Hormez as the metropolitan of Mosul.

In 1743, the Christians of Mosul played an active role in defending the city during the 42-day siege laid by the Persian Nâdir Shâh who had already looted and ransacked the plain of Nineveh. Victorious and grateful, the pasha of Mosul, Husayn Djalîlî “obtained a firman from Constantinople favourable to the churches of Mosul[9].” In 1744, the two al Tāhirā churches were built in Mosul, one for the Chaldeans, one for the Syriac-Catholics. The churches damaged by bombs were also restored.

The 17th century marked the opening of the Latin missions to Iraqi Mesopotamia. The Capuchin Friars open their first house in Mosul in 1636. The Dominicans of the Province of Rome arrived in 1750, followed by those from the Province of France in 1859.

A turning point came in 1915-1918 with the genocide of the Armenians, Assyrians and Chaldeans in the Ottoman Empire. Large numbers of survivors came to live in Iraqi Mesopotamia, specifically in Mosul where there were pre-existing Christian communities. During this period, in January 1916 over the course of just two nights, 15,000 Armenian deportees living in Mosul and the surrounding area were exterminated, tied together in groups of ten and thrown into the Tigris river. Already, well before this carnage, on 10th June 1915, the German consul to Mosul, Holstein, telegraphed his Ambassador, reporting telling scenes: “614 Armenians (men, women and children) expulsed from Diarbekyr and transported to Mosul, were all killed en route, as they were transported by raft (on the Tigris). The kelekarrived empty yesterday. For a few days now the river has been carrying corpses and human limbs (…)” [10]

The fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003 and the rise of Islamic fundamentalism and associated criminal activity, had a considerable impact on the demographic collapse of Christian communities in Iraq, particularly in Mosul. On 1st August 2004, simultaneous attacks against five churches in Mosul and Baghdad triggered the mass exodus of the Christians of Mosul to protected areas in the Nineveh plain, Iraqi Kurdistan and overseas. The next few years in Mosul were truly harrowing. The targeted kidnapping and murders of Christians exacerbated the exodus. On 6th January 2008, Epiphany, and 9th January, criminal attacks targeted several Christian buildings in Mosul and Kirkuk.

It was in this climate of terror that Monsignor Paulos Faraj Rahho, the Chaldean archbishop of Mosul was kidnapped. “On 13th February 2008, as he welcomed a delegation from Pax Christi, in the church in Karemlash, right next to Mosul, the prelate revealed that he had been threatened by a terrorist group several days previously, “Your life or five hundred thousand dollars,” the terrorists told him. “My life is not worth that!” he replied. One month later, on 13th March, Monsignor Rahho was found dead at the entrance to the city.”[11]

From June 2014 to July 2017, Mosul fell into the hands of ISIS fighters. The houses of the 10,000 or so Christians still living in the city were marked with the sign Nazrani(Nazarean, i.e. disciples of Jesus). They were ordered to convert to Islam, pay the djizia(the tax on dhimmi) or die. They fled the city hastily and en massebut had to abandon their Christian heritage which was extensively looted, vandalised and desecrated. The battle of Mosul and the bombing by the international coalition which pulverised the ISIS fighters in a deluge of fire, reduced some of Mosul’s largest Christian (and Muslim) buildings to dust.

_______

[1]In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien »,Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Éditions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p.88

[2]In« Assyrie Chrétienne », vol.II, Jean-Maurice Fiey. Beyrouth, 1965. P. 115-116. See also “Mossoul chrétienne” by Jean-Maurice Fiey.

[3]In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 89

[4]In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien »,Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 92-93

[5]In« Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien »,Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 94

[6]In« Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien »,Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 95

[7]In« Vie et mort des chrétiens d’Orient », Jean-Pierre Valogne, Fayard, March 1994, p.740

[8]In « Histoire de l’Église de l’Orient »,Raymond Le Coz, Cerf, September 1995, p. 328

[9]In« Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien »,Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 97

[10]In « L’extermination des déportés arméniens ottomans dans les camps de concentration de Syrie-Mésopotamie ». N° spécial de la Revue d’Histoire Arménienne Contemporaine, Tome II, 1998. Raymond H.Kevorkian. p.15

[11]In« Chrétiens d’Orient : ombres et lumières »,by Pascal Maguesyan, Éditions Thaddée, September 2013, latest edition 2014, p. 260

History and current presence of the Dominicans in Iraq and in Mosul

This chapter is largely based on the work of Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux o.p. who lived in Iraq for 14 years from 1968 to 1983 as part of the Dominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia, based in Mosul. See, two books by Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux« Va à Ninive ! Un dialogue avec l’Irak », Éditions du Cerf, October 2000; and « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Éditions La Thune, Marseille, July 2015.

_______

The Dominican presence in Mesopotamia constitutes the realisation of the wishes of Saint Dominic (1170-1221) himself, founder of the Order of Preachers (1215). As early as 1235, one of Saint Dominic’s followers Brother Guillaume de Montferrat was sent to the East by Pope Gregory IX. When he arrived in Mesopotamia in 1237, he is said to have gone to Baghdad, to the court of the caliph.

It was in the 18th century that the Order established a lasting presence in the region. The first Fathers of the Dominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia, created by papal decree on 15 December 1749, arrived in Mosul in 1750. Italian members of the Province of Rome, they were sent by Pope Benedict XIV. The first mission superior was Father Domenico Lanza. Respectfully welcomed by the family of the Djalîlî pashas of Mosul, established in their own district during a favourable period for Christians in the Ottoman Empire, the Italian Dominicans laid the foundations for the work accomplished by the Order ever since this time.

After reinstating the Dominican Province of France, thanks to Father Henri Lacordaire, in the period from 1856 to 1858, Pope Pius IX sent eight French Dominicans to Mosul to take over from the Italians. They expanded the schools and in 1862 set up the first print shop in Iraq, which printed numerous books in Arabic, Kurdish and Syriac, including the first bible in Arabic published in Iraq, the Peshitta (the bible in Syriac), as well as the New Testament in West Syriac (…). This remarkable printing press was destroyed by the Ottoman Turks in 1915 during World War I.

In 1878, at the request of Pope Leo XIII, the Dominicans also founded the ecumenical St John seminary for Syriac and Chaldean Catholics. The seminary educated large numbers of lay and consecrated men and women who went on to become great scholars, often using French perfectly fluently.

In 1873, six Dominicans from the community of the Sisters of the Presentation in Tours arrived in Mosul, followed in 1877 by Dominican Sisters of Saint Catherine of Siena. They accomplished their apostolic, educational and medical mission amongst women in particular, notably setting up a hospice, dispensary, orphanage and schools for girls in Mosul.

During the First World War, the French Dominicans witnessed first-hand the genocide of the Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans and Syriacs perpetrated by the Young Turk leaders of the Ottoman Empire. Expelled from Mosul in 1915, they returned in 1919-1920 when the mandate for Mesopotamia was entrusted to the British.

Despite the closure of the Saint John seminary in Mosul in 1976 and the forced departure of the French Dominicans, the Dominicans continue to maintain a presence in Iraq. In 1995, the Dominicans were also given reponsibility for the famous avant-garde review La Pensée Chrétienne, created 31 years previous in Mosul by the community of priests of Christ the King.

Since 2003, the brothers and sisters of the Order of Saint Dominic continued their apostolate against all odds, whilst experiencing the same suffering and catastrophes as the people and country of Iraq.

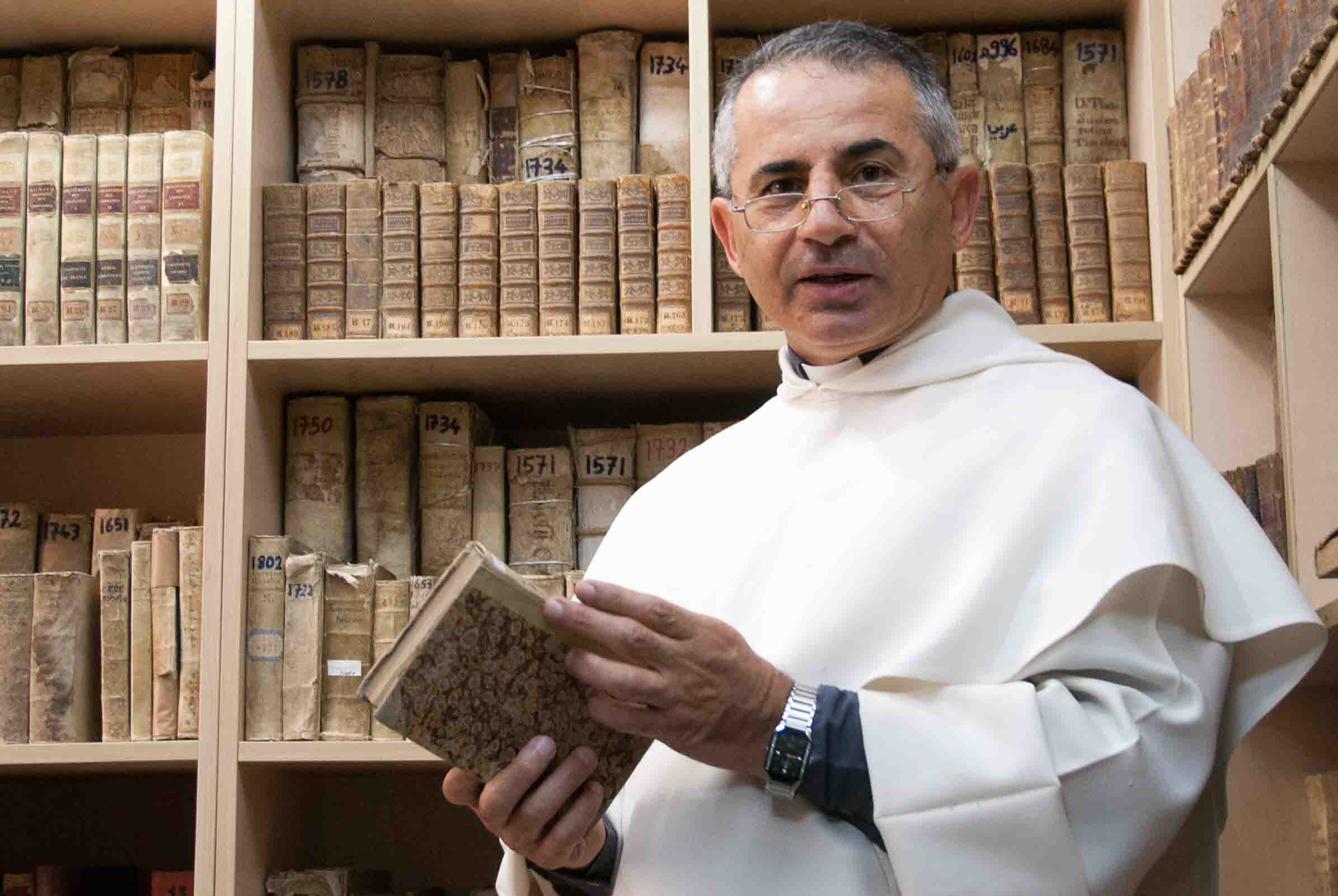

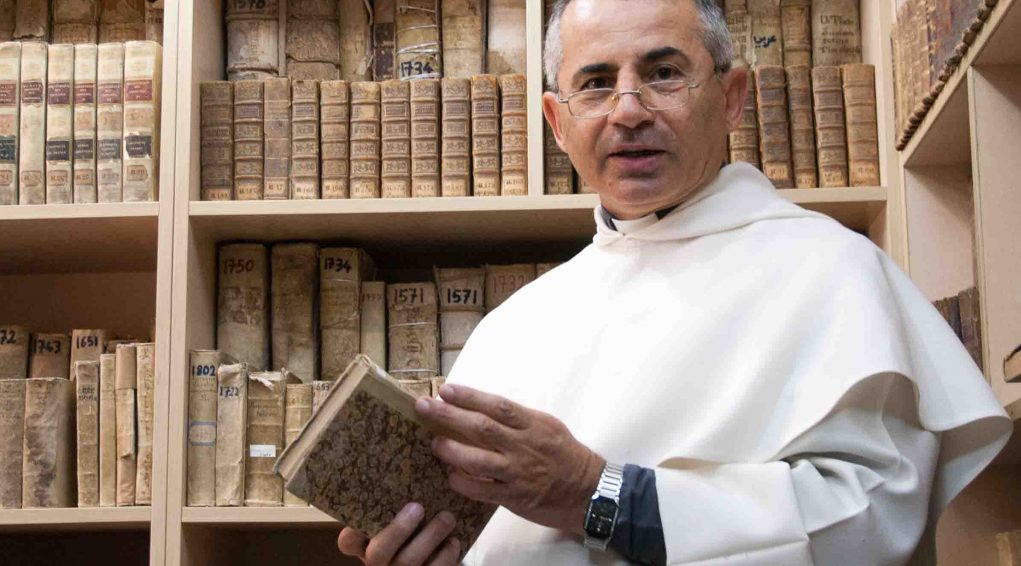

Significant figures emerged from this chaos such as Najeeb Michaeel, appointed Chaldean archbishop of Mosul by Pope Francis on 22nd December 2018.[1]Having founded the Digital Center of Eastern Manuscripts in the 1990s, he moved the centre and its archives, which span the centuries, from Mosul to Qaraqosh, then from Qaraqosh to Erbil, under pressure from criminal and Islamicist groups, often in entirely improbable, and sometimes dramatic, circumstances. We should also highlight the remarkable commitment of Monsignor Thomas Yousif Mirkis, archbishop of Kirkuk. Born in Mosul, this emminent Iraqi theologian, linguist, historian and anthropologist, former superior of the Dominican community, runs a plethora of educational, social and spiritual projects benefitting all denominations.

Finally, it should be noted that the ancient archives of the Dominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia were transferred to Paris to the Saulchoir library, next to the Dominican convent of Saint James. Their Mosul collection recounts in texts and images the incredible missionary adventure in Iraq.

_______

[1]Monsignor Najeeb Michaeel was ordained bishop on 18th January 2019, at Saint Joseph’s cathedral in Baghdad, by the Chaldean patriarch, Louis Raphaël I Sako. The cardinal and archbishop of Lyon Philippe Barbarin, who instigated the twinning of the dioceses of Lyon and Mosul, took part in this episcopal ordination.

History and description of the Our Lady of the Hour Latin church of the Dominicans in Mosul (at the height of its splendour)

The Latin church Our Lady of the Hour goes by several names in Mosul: Kanissat al latine(the Latin church), Kanissat al Dominikâne(the church of the Dominicans), Kanissat al Pawater(the church of the Fathers) and most commonly Kanissat as-Sâa(the clock church). By extension it is also referred to a Deir el-aba (convent of the fathers) and even Umm al-a’joûby (mother of miracles) after the cave of the Virgin Mary found there.

The first Dominican church in Mosul was built by the Italians. This was replaced by the new Latin church built between 1866 and 1873 by the Dominicans of the Province of France. The work was overseen by Fathers Duval and Lion.

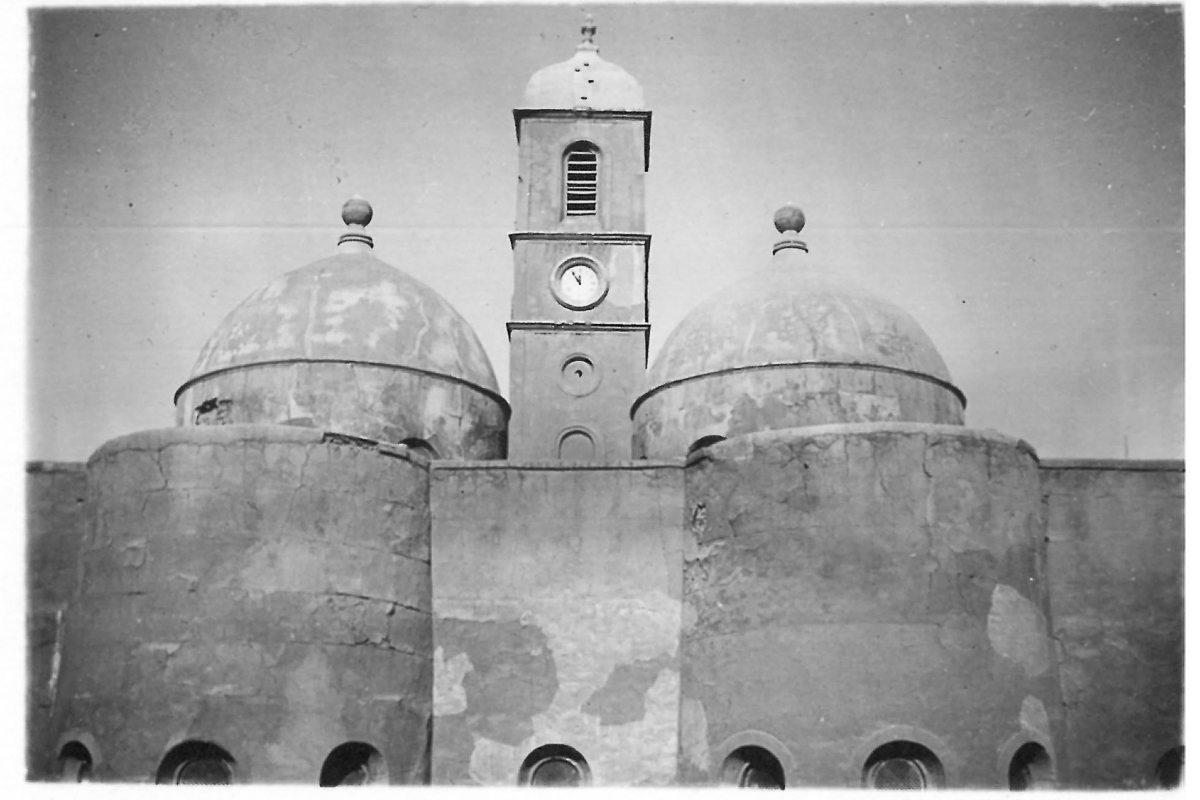

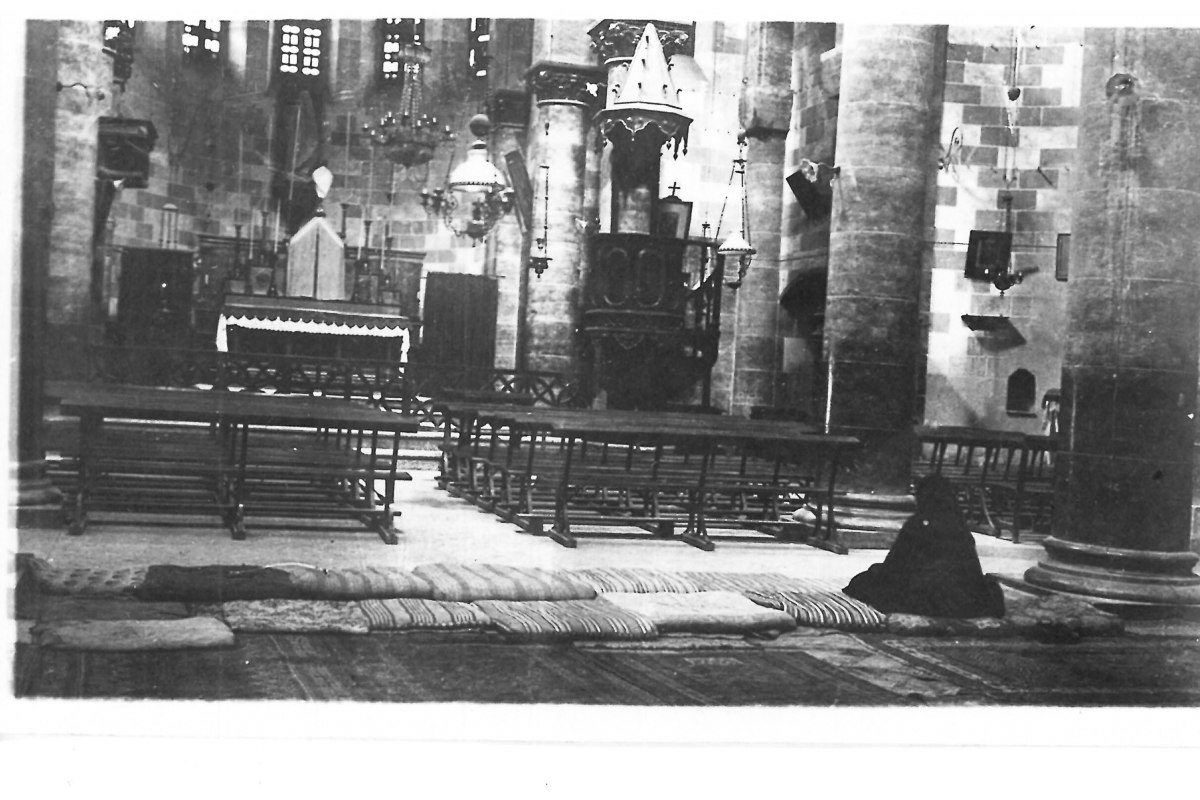

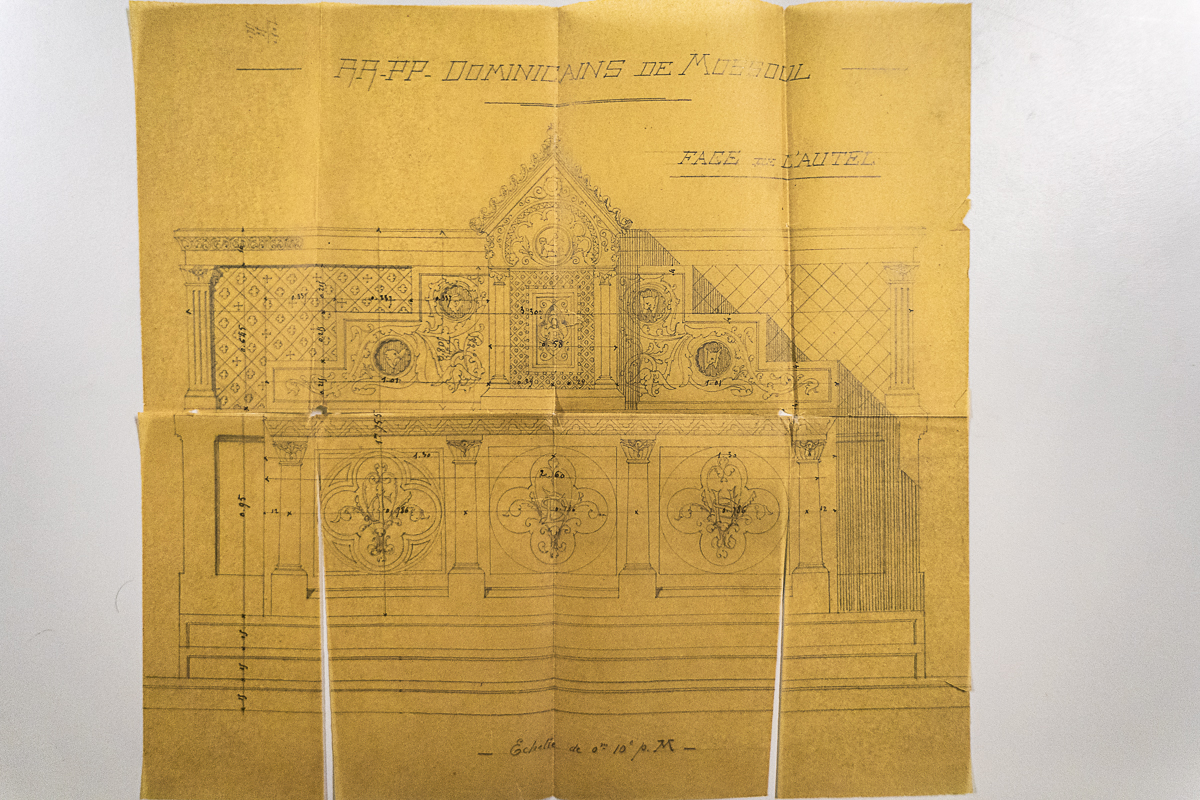

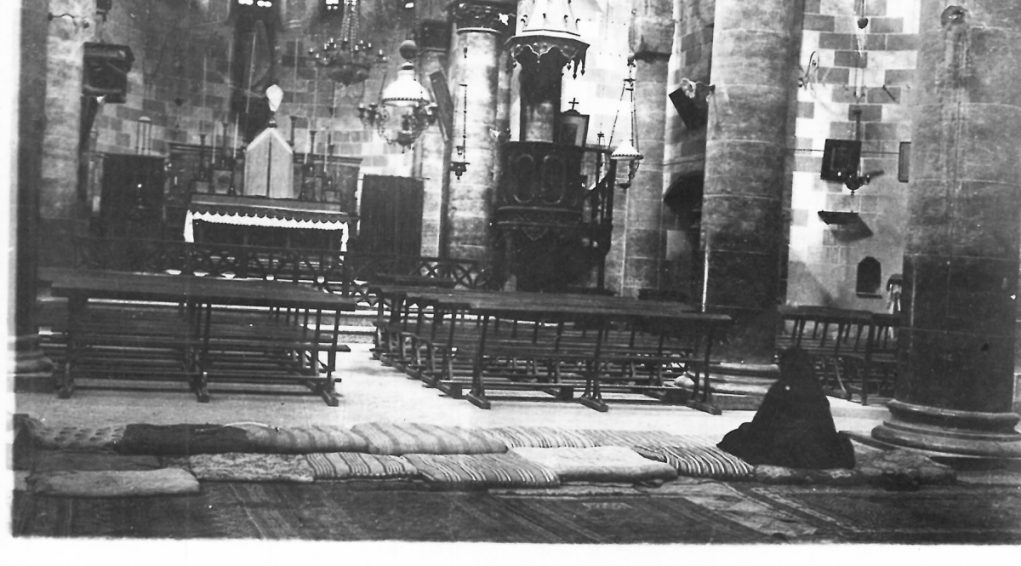

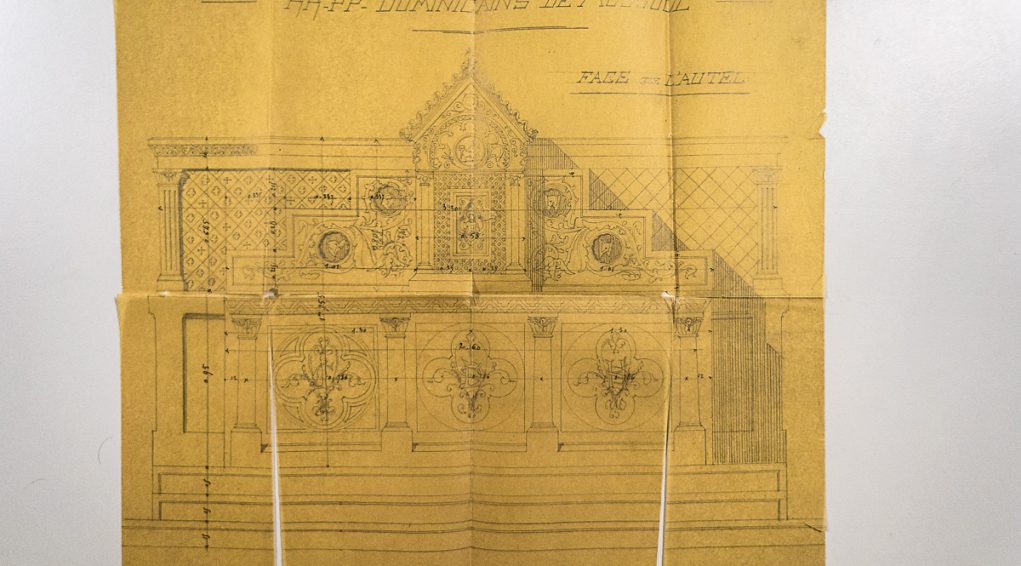

It is an imposing building, both solid and slender, [1]“in the Byzantine style”with a triple nave and five transepts. The structure of the building is supported by four pairs of cylindrical pillars mounted with acanthus-leaf capitals and semi-circular arches. There are two semi-spherical drum domes and windows above the centre of the nave. The sanctuary has no royal door. The high altar is installed in the apse with a semi-dome vault. Opposite the sanctuary, another perfectly symmetrical apse houses a high tribune. To both the north and the south, the walls are formed from four large apse chapels which contain four finely sculpted altars.

The church’s interior is decorated with the magnificent grey marble of Mosul. The exterior is covered with beige and ochre stone facing

This church also has a funeral chamber which contains the tombs of Dominican Fathers, including Fathers Hyacinthe Simon and Jacques Rhétoré, who witnessed all hell break loose on the Christians of the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire in 1915-1916 and recounted this in their writings.

The famous clock tour of the church of Our Lady of the Hour is found to the north of the building between two apse chapels. The Empress Eugénie de Montijo, wife of Napoleon III, gifted this clock tower, the first in Iraq, in 1876. The clock installed in 1880 was a famous four-dial clock financed by the French government at the request of the French consulate in Mosul. This was how the clock came to give the time to the whole city.

In the courtyard of the church is a replica of the rock cave of Lourdes, which contains a large statue of Our Lady of Miracles (Omm al-ajoubi), where women, Christian, Muslim and Yazidi, all come to pray and ask for grace and blessings. The Dominican scholar Jean-Maurice Fiey built this cave, to replace the Chapel of the Virgin Mary which was destroyed when the Farouq road was built.

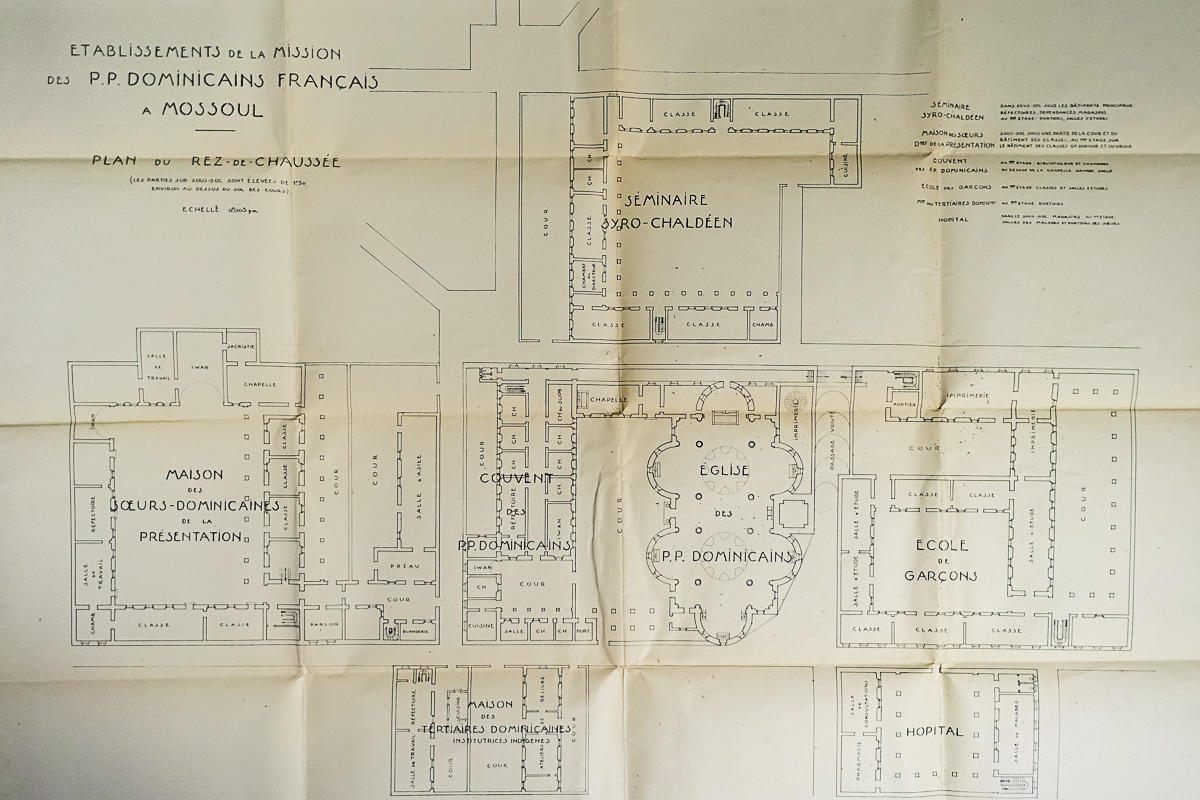

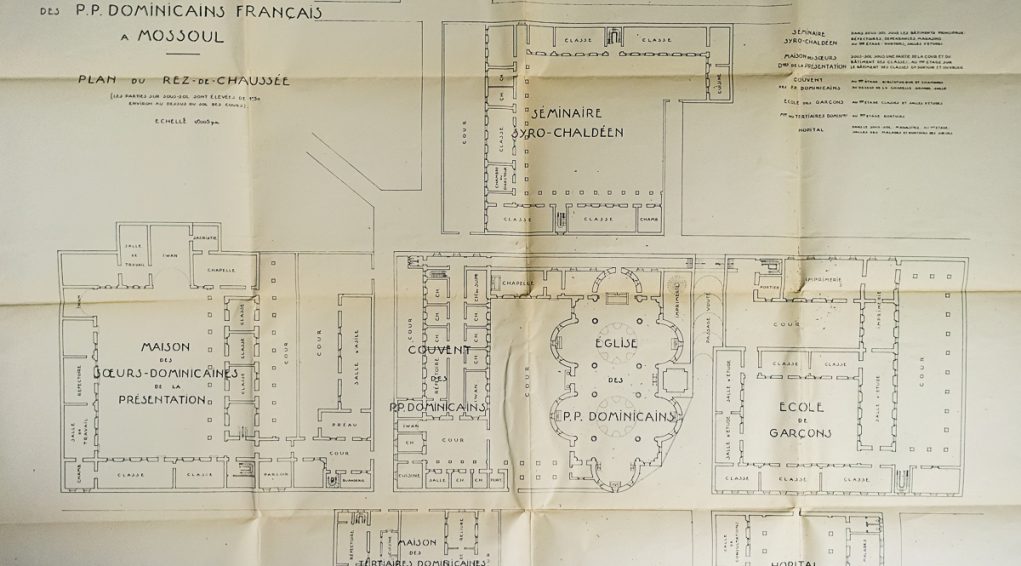

Around the church there is:

To the west: the Syrio-Chaldean seminary composed of study rooms, bedrooms, a refectory and a courtyard.

To the south: the monastery of the Dominican Fathers, on the other side of the church courtyard and the House of the Dominican Sisters of the Presentation. This vast house contains numerous classrooms, a chapel, an iwan, several courtyards and covered areas, a laundry, dormitories and workrooms.

To the east: the house of the Dominican tertiaries and school teachers, which contains a book binding workshop.

To the north: a hospital containing the patient wards, a consultation room, a pharmacy and the Sisters’ dormitories. Closer to the church, is the boys’ school with numerous classrooms, two courtyards and a printshop.

_______

[1]In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 102

Looting and destruction in the period 2014 - 2017

Restored in the 2000s, the convent was looted and ransacked during the three years Mosul was occupied by ISIS from 2014 – 2017.

There is nothing left of the library (see below the first-hand account from Father Michaeel Najeeb), whichis a disaster in heritage terms.

The four dials and mechanism of the clock were stolen from the church of Our Lady of the Hour(see below the first-hand account from Sister Luigina Sako).

Several parts of the church were destroyed with explosives,most notably on 24th April 2016. In the courtyard, the replica of the cave in Lourdes and its statue of the Virgin Mary were blown to smithereens. After the liberation of Mosul, the bodies of fundamentalist fighters laid lifeless in the church.

Mutilated, but still standing, the Dominican Latin church of Our Lady of the Hour in Mosulhas become a beacon of sorrow in an ocean of anguish.

Testimony

Father Michaeel Najeeb[1], Founder and Director of the Digital Center of Eastern Manuscripts[2]“I discovered this passion for ancient texts basically by chance when I wanted to reference the collection in the library of our monastery in Mosul at the end of the 1980s (…) 12th century manuscripts and 16th century incunables with camel-skin covers sat alongside recently-published works because the subject matter was more or less connected. (…) Once, by chance, I noticed a piece of parchment hidden in the binding of a book. It was a 9th century text in Latin which recounted the life of Moses. Sometimes the library bookshelves contained only “ghosts”. These cards inserted in place of the borrowed book, with the title, date borrowed, and date returned, constitute a fabulous testimony, retracing the genealogy of the work: who read it? when? for how long? Studying these cards allowed us to reconstitute the intellectual development of the consecrated men and women here and the debate which animated the monastery. The most ancient date back to 1870 and reveal the breadth and depth of the curiosity of the Dominicans. There are traces of the reading of Muslim scholars, motivated by the same passion as us. They would never have dreamed of destroying this library. Yet this is exactly one of the first things the madmen of ISIS did as soon as they took control of Mosul, when they turned our monastery into a place of torture. Thanks to these ghosts, I understood that dozens of ancient manuscripts had disappeared. I therefore turned myself into a makeshift librarian.”

Sister Luigina Sako, Superior of the Roman house of the Chaldean Sisters of the Daughters of Mary Immaculate:“The chiming of this clock accompanied our childhood, at a time when Mosul was a city where everyone lived together in peace. I remember when we were studying, when we had an important exam, we all, Christians and Muslims together, took messages with our requests for help to the Lourdes cave in the church, a cave our Muslim friends knew and worshipped as the church of Our Lady of Miracles.”[3]

_______

[1]The new Chaldean Archbishop of Mosul since 22ndDecember 2018

[2]In « Sauver les Livres et les hommes », Father Michaeel Najeeb with Romain Gubert, Édition Grasset. p.26-27.

[3]Article first published in the La Croix newspaper, April 2016. Reproduced with the kind permission of the publication.

Progress of restoration work in November 2022 and April 2023

Restoration work on the Our Lady of the Hour Dominican Latin church in Mosul continues.

Work began on January 4, 2021.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute