The al-Tahira Syriac-Catholic church in Mosul

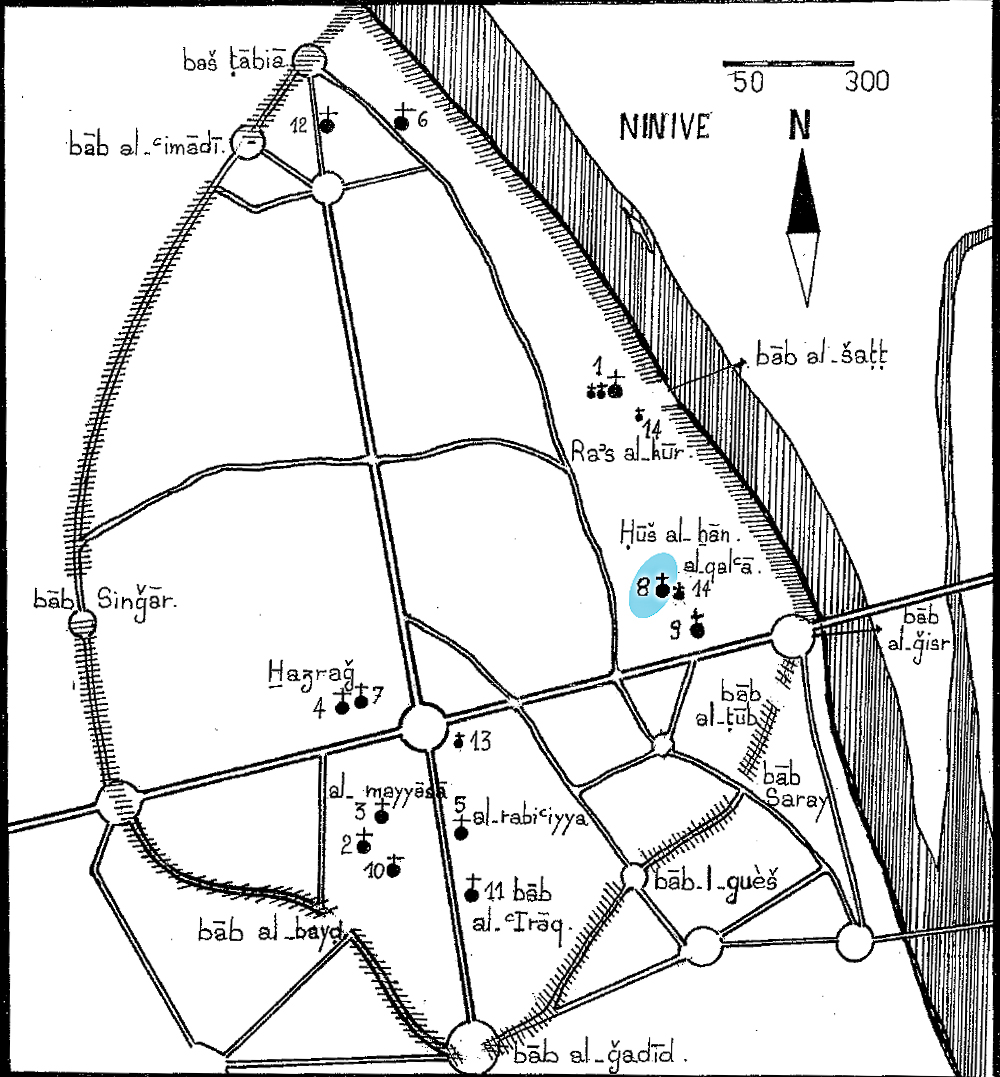

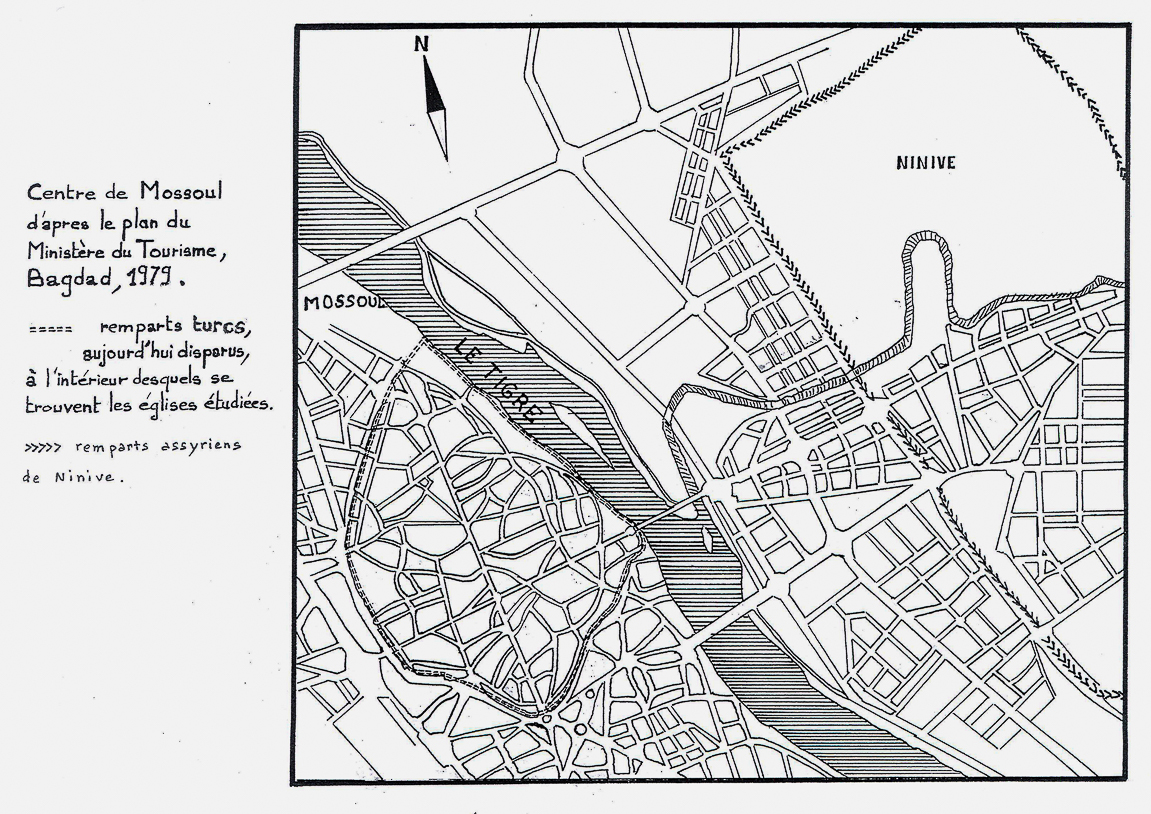

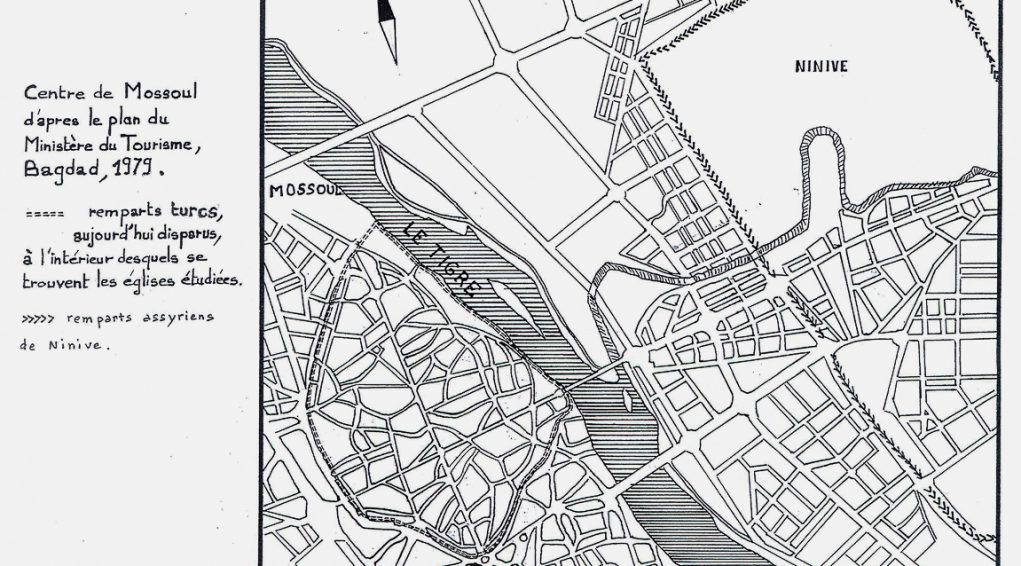

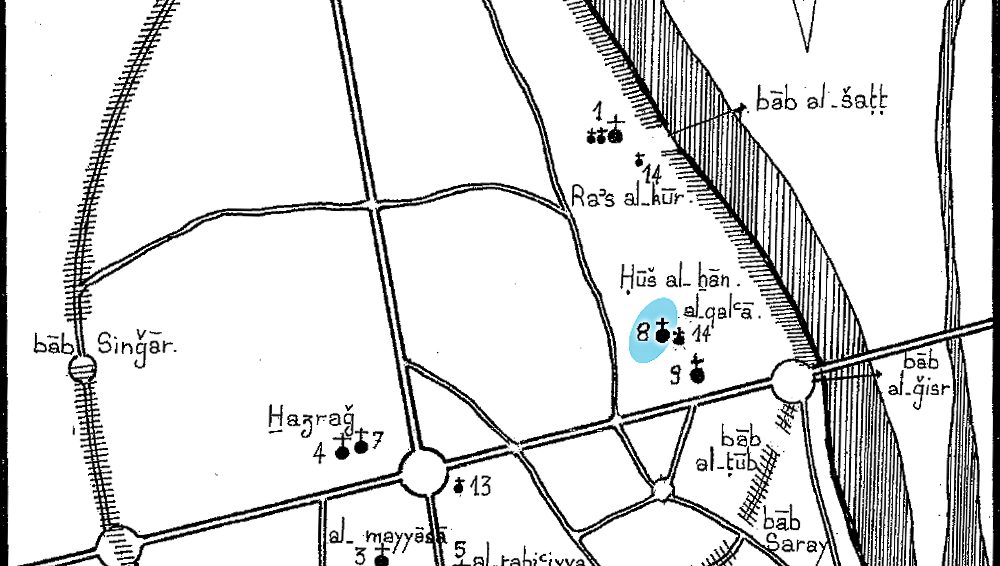

The al-Tahira Syriac-Catholic church is located at 36°20’40.4″N 43°07’57.5″E and 237 metres altitude, in the old city of Mosul, formerly designated by the Ottoman city walls on the west bank of the Tigris river, opposite ancient Nineveh.

The (ancient) al-Tāhirā Syriac-Catholic church of Mosul is mentioned for the first time in a colophon from 1672. Its restoration in 1744, authorised by an Ottoman firman, was no doubt an entirely unexpected opportunity to extensively renovate, almost rebuild, the church and this is apparent in the building’s architectural style. However, the church’s location in the oldest neighbourhood of Mosul, and the fact that it is partially buried, suggest that the church’s foundations are probably very ancient, perhaps dating as far back as the 7th century.

| Plan of the Syriac-Catholic Al-Tahira church (ancient) in Mosul 1: Altar. 8: Baptistery. 11: Doors. 13: oratory © in “Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815.” Fr.Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p., Mossoul-Ninive, 1983, p.117, A. |

Name

The al-Tāhirā Syriac-Catholic church in Mosul goes by several names: Tāhirā of the Syrians for its denominational identity, the interior Tāhirā as opposed to the exterior Tāhirā (Syriac-Orthodox) located in the far north of the old city of Mosul, and finally ancient Tāhirā as opposed to the new Syriac-Catholic al-Tāhirā church.

Location

The (ancient) al-Tahira Syriac-Catholic church is located at 36°20’40.4″N 43°07’57.5″E and 237 metres altitude, in the Qala district, close to the crossroads between the Nabi Guorguis road and the road to Nineveh, in the heart of the old city of Mosul, formerly designated by the Ottoman city walls on the west bank of the Tigris river, opposite ancient Nineveh, and 400 kilometres to the north of Baghdad.

It stands at the centre of a square around which there are several Christian buildings: the new al-Tāhirā Syriac-Catholic cathedral, the al-Tāhirā Syriac-Orthodox cathedral, the Armenian Apostolic church and finally the Syriac-Catholic seat of the archdiocese.

At the origin of the Syriac-Catholic church

Syriac tradition attributes the evangelization of Mesopotamia to the apostle Thomas and his disciples Addai and Mari, however,“it seems that the introduction of Christianity in fact only dates back to the beginning of the 2nd century and that it was conducted under the influence of Judaeo-Christian missionaries from Palestine[1]. This Mesopotamian Christianity started organizing itself in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, on the banks of the Tigris River, 30 kilometres south of Baghdad, where tradition tells us that Saint Thomas made a halt on his way towards India. And it is right here, on a hill of the Koghe district, that the first patriarchal church of the Church of Mesopotamia was built and its Catholicate established. This Syriac-language-based primitive Christianity still forms the shared foundation of the local Iraqi churches and their communities, which perpetuate and pass on this Christian heritage.

This common foundation progressively broke up into a multitude of different churches over the period stretching from the Council of Nicaea in the 4th century up into the 20th century, often due to geopolitical, rather than religious, considerations.

Indeed, the first ecumenical Council of Nicaea in 325, convened by the Roman Emperor Constantine I, was held without the Persian bishops, except for Jacob of Nisibis, as “it was out of the question to the other bishops, in times of never-ending or nearly never-ending war, to go and sit in an assembly held in an enemy country, convened – and what’s more presided over – by the Roman Emperor[2]”. It must be said that from the time of Constantine’s conversion to Christianity on, the Sassanid Emperor Shapur II’s attitude to Persian Christians turned from tolerance to mistrust. This mistrust eventually turned into hostility, churches were destroyed and the clergy persecuted. “The aim of the persecution was not to annihilate the Christians but to lead them to apostasy, once the hierarchy of the church had been wiped out.[3]”

A century later, in 431, the Council of Ephesus sentenced the Patriarch of Constantinople Nestorius, who professed the two distinct natures of Christ (hypostasis): one divine, as the son of God, and one human, as the son of Mary. This Christological thesis was considered heretical and Nestorius was removed from office. Spurred on by geopolitical rivalries between the Roman Empire and the Persian Sassanian Empire, the Church of the East turned to Nestorianism from the second half of the 5th century onwards, and spread throughout Mesopotamia, Persia and up into India.

Twenty years later, in 451, the Council of Chalcedon was the staging for a new Christological controversy. The Syriac, Egyptian, Ethiopian and Armenian Churches were blamed for professing monophysite theory i.e. that within the person of Jesus Christ, his human nature was absorbed into his divine nature, and that Christ has only one divine nature. This controversial doctrine led to a further split and the churches concerned became autocephalous, with a view to preserving their own geopolitical interests.

In the 6th century, Saint Jacob Baradaeus, a Syriac monk, reorganised the Syriac church. After his episcopal ordination, he embarked on a lengthy journey visiting all the Syriac regions to ordain large numbers of bishops, priests and deacons. It is in his honour that the Syriac church is characterised as “Jacobite”.

There was a schism in the Orthodox church in the 18th century, in 1783, which gave rise to the Syriac-Catholic church in full communion with Rome.

_______

[1]In “Vie et mort des chrétiens d’Orient. Des origines à nos jours”, Jean-Pierre Valogne, Fayard, March 1994, p.737

[2]In Histoire de l’Église de l’Orient, Raymond le Coz, published by Éditions du Cerf, 1995, p.31.

[3]In Histoire de l’Église de l’Orient, Raymond le Coz, published by Éditions du Cerf, 1995, p.33.

Fragments of the Christian history of Mosul

This chapter is largely based on the work of Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux o.p. who lived in Iraq for 14 years from 1969 to 1983 as part of the Dominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia, based in Mosul. See, two books by Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux, in particular: « Va à Ninive ! Un dialogue avec l’Irak », Éditions du Cerf, October 2000; and « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Éditions La Thune, Marseille, July 2015.

Mosul “remains a Christian metropolis,”[1] as attested by its history, and its ancient and modern heritage, which persists despite recent catastrophic events.

Although the first archdiocese is attested to in 554,[2] it is also important to take into account the Paleo-Christian apostolic tradition. “Three churches are proud to be founded on houses where apostles are said to have stayed. The Sham’ûn al-Safa’ church, built during the Atabeg period in the 12th – 13th centuries, is said to be built where Saint Peter stayed during his visit to Babylonia and the Mar Theodoros church is connected to the visit of the apostle Bartholomew. As for the apostle Saint Thomas, the house where he was shown hospitality on his journey to India, became a church.”[3] The church in question is the Syriac-Orthodox church Mar Touma described herein.

The first church attested to in Nineveh (modern-day Mosul-East) dates back to the year 570. It is the Mar Isha’ya church which is even mentioned in the “Chronicle of Seert”. This confirms a pre-existing Christian community. In the 7th century the Syriac-Orthodox Mar Touma church was also known of. From the 7th century onwards, the Mar Gabriel monastery was the seat of one of the Church of the East’s most important schools of theology and liturgy. The al-Tāhirā Chaldean church was built on the site of this monastery in the 18th century.[4]

Over the centuries, through successive councils and conflicts, a multitude of churches of different denominations, including the Armenian and Latin churches, were formed.

Of these various fragments of history, the Muslim conquest must be cited as one of the most important. Mosul fell in 641 and the Christian members of its population became dhimmis, with (limited) rights and (stringent) obligations based on their religious identity. This status remained in force up until the 19th century and was abolished in the Ottoman Empire in 1855. Despite this abolition, Christians (and Jews) still remain defined by their dhimmi status which governs denominational relations in public life and attitudes in almost all Muslim countries. It is still legally enforced (in Iran).

In the 7th and 13th centuries, at the height of the Seljuq period, the Atabeg dynasties imposed their rule throughout Iraqi Mesopotamia and made Mosul a centre of power. At this time, Syriac-Orthodox Christians persecuted in Tikrit fled to the Nineveh plain and Mosul, where they established their community and founded the Mar Ahûdêmmêh (Hûdéni) church. “At the end of the 20th century due to below-ground flooding throughout the neighbourhood, the Mar Hûdéni church located well below ground level was flooded and had to be abandoned”. A new church was built right on top of the old one. Thankfully, the royal door in the Atabeg style, described by Father Fiey as a “jewel of 13th century Christian sculpture”, was transported to the new church and given pride of place. [5]

Following on from the Atabeg, the Mongol Houlagou Khan, took Mosul but spared the city from destruction and from the massacres committed in Baghdad in 1258, thanks to the “cunning governor of the city, Lû’lû’, of Armenian origin.”[6] The following century was nonetheless a tragic one. “Christian persecutions peaked under Tamerlan, whose armies ravaged the Middle East in the first years of the 14th century and exterminated the Christian populations. No other eastern Christian church underwent anything close to this type of eradication, the community in Iraq is well placed to claim the first prize in martyrdom.”[7]

In 1516, Mosul fell into the hands of the Ottoman Turks for the first time, but it was not until the following century that they established a dominant presence in Iraqi Mesopotamia that was to last for four centuries after the conquest of Baghdad in 1638 by the sultan Murad IV.

In the 16th century Mosul was a major centre of Christian influence. It was here that the schism of the Church of the East took place, with the election of Yohannan Sulaqa as the first patriarch of the Chaldean church. Abbot of Rabban Hormizd Monastery in Alqosh, he took the name Yohannan/John VIII and travelled to Rome to profess the Catholic faith. On 20th April 1553 Pope Julius III named him patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic church marking “its official birth.”[8] After Diyarbakır (in the south-east of modern-day Turkey) and before Baghdad (in 1950), the seat of the Chaldean church was established in Mosul in 1830, with the election of Jean VIII Hormez as the metropolitan of Mosul.

In 1743, the Christians of Mosul played an active role in defending the city during the 42-day siege laid by the Persian Nâdir Shâh who had already looted and ransacked the plain of Nineveh. Victorious and grateful, the pasha of Mosul, Husayn Djalîlî “obtained a firman from Constantinople favourable to the churches of Mosul[9].” In 1744, the two al Tāhirā churches were built in Mosul, one for the Chaldeans, one for the Syriac-Catholics. The churches damaged by bombs were also restored.

The 17th century marked the opening of the Latin missions to Iraqi Mesopotamia. The Capuchin Friars open their first house in Mosul in 1636. The Dominicans of the Province of Rome arrived in 1750, followed by those from the Province of France in 1859. Under their impulsion, the large Latin church Our Lady of the Hour, was built “in the Byzantine style, between 1866 and 1873.” [10] This is the church to which the empress Eugénie de Montijot, wife of Napoleon III, donated the famous clock which was placed in the first clock tower ever built in Iraq. For almost three centuries, members of the Dominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia, have been actors, experts and vital witnesses to the history of Christianity in Iraq and the dangers facing Christians in the Middle-East.

A turning point came in 1915-1918 with the genocide of the Armenians, Assyrians and Chaldeans in the Ottoman Empire. Large numbers of survivors came to live in Iraqi Mesopotamia, specifically in Mosul where there were pre-existing Christian communities. During this period, in January 1916 over the course of just two nights, 15,000 Armenian deportees living in Mosul and the surrounding area were exterminated, tied together in groups of ten and thrown into the Tigris river. Already, well before this carnage, on 10th June 1915, the German consul to Mosul, Holstein, telegraphed his Ambassador, reporting telling scenes: “614 Armenians (men, women and children) expulsed from Diarbekyr and transported to Mosul, were all killed en route, as they were transported by raft (on the Tigris). The kelek arrived empty yesterday. For a few days now the river has been carrying corpses and human limbs (…)” [11]

The fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003 and the rise of Islamic fundamentalism and associated criminal activity, had a considerable impact on the demographic collapse of Christian communities in Iraq, particularly in Mosul. On 1st August 2004, simultaneous attacks against five churches in Mosul and Baghdad triggered the mass exodus of the Christians of Mosul to protected areas in the Nineveh plain, Iraqi Kurdistan and overseas. The next few years in Mosul were truly harrowing. The targeted kidnapping and murders of Christians exacerbated the exodus. On 6th January 2008, Epiphany, and 9th January, criminal attacks targeted several Christian buildings in Mosul and Kirkuk.

It was in this climate of terror that Monsignor Paulos Faraj Rahho, the Chaldean archbishop of Mosul was kidnapped. “On 13th February 2008, as he welcomed a delegation from Pax Christi, in the church in Karemlash, right next to Mosul, the prelate revealed that he had been threatened by a terrorist group several days previously, “Your life or five hundred thousand dollars,” the terrorists told him. “My life is not worth that!” he replied. One month later, on 13th March, Monsignor Rahho was found dead at the entrance to the city.”[12]

From June 2014 to July 2017, Mosul fell into the hands of ISIS fighters. The houses of the 10,000 or so Christians still living in the city were marked with the sign Nazrani (Nazarean, i.e. disciples of Jesus). They were ordered to convert to Islam, pay the djizia (the tax on dhimmi) or die. They fled the city hastily and en masse but had to abandon their Christian heritage which was extensively looted, vandalised and desecrated. The battle of Mosul and the bombing by the international coalition which pulverised the ISIS fighters in a deluge of fire, reduced some of Mosul’s largest Christian (and Muslim) buildings to dust.

_______

[1] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Éditions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p.88

[2] In « Assyrie Chrétienne », vol.II, Jean-Maurice Fiey. Beyrouth, 1965. P. 115-116. See also “Mossoul chrétienne” by Jean-Maurice Fiey.

In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux.[3] Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 89

[4] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 92-93

[5] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 94

[6] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 95

[7] In « Vie et mort des chrétiens d’Orient », Jean-Pierre Valogne, Fayard, March 1994, p.740

[8] In « Histoire de l’Église de l’Orient », Raymond Le Coz, Cerf, September 1995, p. 328

[9] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 97

[10] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 102

[11] In « L’extermination des déportés arméniens ottomans dans les camps de concentration de Syrie-Mésopotamie ». N° spécial de la Revue d’Histoire Arménienne Contemporaine, Tome II, 1998. Raymond H.Kevorkian. p.15

[12] In « Chrétiens d’Orient : ombres et lumières », by Pascal Maguesyan, Éditions Thaddée, September 2013, latest edition 2014, p. 260

History of the (ancient) al Tāhirā Syriac-Catholic church in Mosul, prior to its destruction.

“The first historical record of this church is found in a colophon dating back to 1672[1].”The building therefore existed before the Persians launched their offensive and laid siege to the city in 1743, but it is impossible to date its foundation more accurately. Various elements can be used to date the building, including the stones re-used in the iconostasis which could be from the 12th– 13thcenturies[2]. “The location of this church in the most ancient district of Mosul suggests a particularly ancient building, founded towards the 7th century[3].”

In addition, “there is an inscription indicating that the church was restored in 1744 following the attack by the Persians[4].”The precise nature of this restoration remains unclear, but the Ottoman firman issued on this occasion may have offered an unexpected opportunity to entirely renovate or even practically rebuild the church. This hypothesis is supported by the building’s architecture, “the overall style of thechurch is indeed in the Ğalīlīstyle[5].”

Further restorations were undertaken, firstly the royal door in 1795, then in 1809 as indicated in an inscription on a pillar of the central nave, and in 1821 when work was done on the outside western door of the church.

_______

[1]In « Les églises et monastères du Kurdistan irakienà la veille et au lendemain de l’islam ». Thesis by Narmen Ali Muhamad Amen. Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, University, 2001. P.270-273.

[2]Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p., in « Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815 », Mossoul, Ninive, 1983. P.112 onwards.

[4]In « Les églises et monastères du Kurdistan irakienà la veille et au lendemain de l’islam ». Thesis by Narmen Ali Muhamad Amen. Saint-Quentin-en-Yvelines, University, 2001. P.270-273.

[5]Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p., in « Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815 », Mossoul, Ninive, 1983. P.112 onwards.

Description of the (ancient) al-Tāhirā Syriac-Catholic church, prior to its destruction.

The church is entered via a courtyard that is below ground level. It is therefore situated “almost three metres below the current ground level of the square”and is partially buried, attesting once again to its ancient origins. [1]

The al Tāhirā (the ancient) church presents as an Assyrian basilic of around 18 metres’ long, from the western entrance to the sanctuary to the east and 24 metres’ wide from the Saint James Intercisus chapel to the south to the baptistery to the north. The church is composed of three transepts, separated by four pairs of columns and very thick pillars which support the vault of the building. The sanctuary is accessed via four doors, including the royal door.

From the south to the north of the building, we can distinguish:

A. The chapel of Saint James Intercisus (the Mutilated) whichoccupies the southern part of the building. It is a single-nave chapel of around 12 metres in length, with an altar under a canopy connected to the sanctuary in the main nave by two side doors. In the right-hand corner of the chapel is a niche said to contain the remains of Saint James Intercisus.

The chapel has no access to the exterior. It can only be accessed via the main church or via a small narthex to the south.

Some authors have used the name of the chapel of Saint James Intercisus to designate the building as a whole.

B. The main nave opens onto a sanctuary with a high altar under a canopy. The large royal door which separates the nave from the sanctuary is equipped with a wooden door which is only opened during services[2].

Above the royal door, these two lines are engraved in the marble in Garshuni Arabic: [3] God, who sanctified the Altar of the Ancients made by Moses, the first of the prophets, sanctify, in your mercy, the altar of the faithful, which will become forgiveness for the sins of the sinners. In 1744 the church of the Blessed Virgin Mary, was restored by the attentions of Sire cIsā, as well as those of the priests, deacons and people.May the Lord reward them in the Kingdom of Heaven.

On either side of this royal door, are two dormer windows, above which there are inscriptions in Syriac.

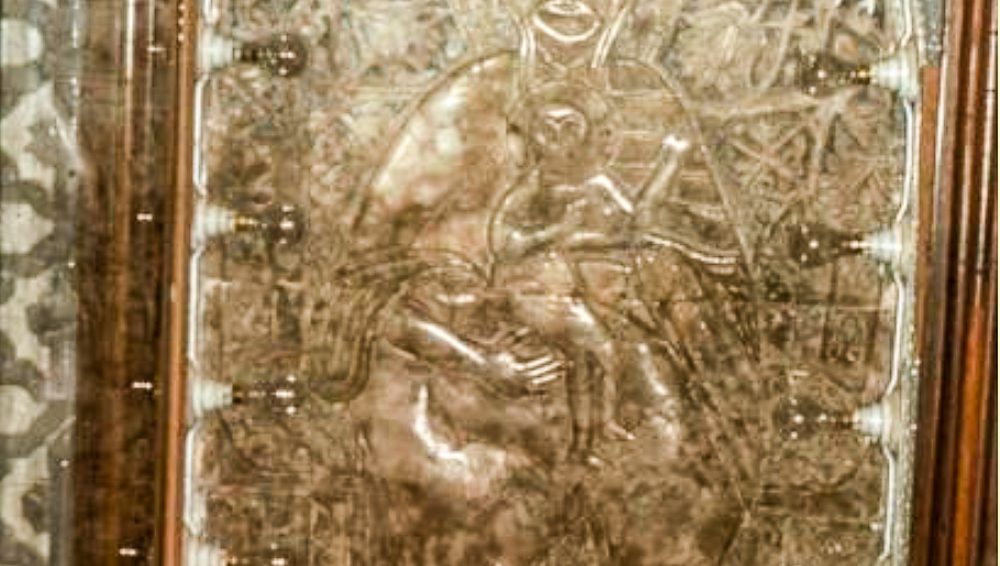

The main nave contains a truly exceptional architectural feature. The two thick columns on the right are“connected by an extraordinary stone iconostasis (…) built in honour of the Virgin Mary, who protected Mosul in 1743.”It shows the mother carrying the child, in a style which is “reminiscent of the most ancient miniatures in Syriac manuscripts.”[4]

C. On either side of the royal door are two side doors accessing the sanctuary. The south door opens onto the diaconicon and the north door opens onto a secondary altar. Above this northern door are two inscriptions in Garshuni Arabic, in the form of two small rosettes.[5]

D. The north side aisleat the far side of the building contains the tombs of priests and bishops and to the east leads into a baptistery fitted with an eight-sided baptismal font with no inscriptions. This side aisle is located under the road which separates the ancient al-Tāhirā church from the new one.

_______

[2]In “Les églises et monastères du Kurdistan irakienà la veille et au lendemain de l’islam”. Thesis by Narmen Ali Muhamad Amen. Saint Quentin en Yvelines University, 2001. P.270-273.

[3]Translations Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p

[4]Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p., in « Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815 », Mossoul, Ninive, 1983. P.112 onwards.

[5]Full inscriptions translated by Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux, o.p., in « Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815 », Mossoul, Ninive, 1983. P.112 onwards.

What remains of the (ancient) al-Tāhirā Syriac-Catholic church?

Bombarded during the mass raids on old Mosul in 2017, the al-Tāhirā (the ancient) church was severely damaged. The roof collapsed, but the royal door and the side doors to the sanctuary remained standing. Unfortunately, at the end of 2018, careless post-war reconstruction work actually worsened the destruction.

The church is currently undergoing restoration. The Syriac-Catholic bishop of Mosul, Monsignor Petros Mouché, has delegated the project management to the French charity Fraternité en Irak, which has already work on the restoration of the Mar Behnam and Sarah martyrion in the Nineveh plain. This is a project of major interest in terms of heritage conservation.

For the Fraternité en Irak architect Guillaum, “some interesting features remain, including at least two of the three arches between the nave and the choir, as well as a number of sculptures. Overall, I think we can rebuild and preserve most of the interesting heritage features which we should be able to find in the rubble.”[1]

_______

[1] Fraternité en Irak plans to rebuild the ancient al-Tahira Syriac-Catholic church in Mosul

What remains of the new Tahira?

The modern al-Tāhirā cathedral, built in the 19th century as an extension to the ancient church was entirely gutted and destroyed during the bombing of Mosul in 2017. At the end of the war only part of the apse was still visible. It would appear that there is nothing of the building to be saved.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute