The Church of Our Lady of the Seeds in Faysh Khabur (Mariam Adra Hafita Al Zorova)

The Church of Our Lady of the Seeds in Faysh Khabur is located at 37°04’27.7″N 42°22’33.3″E and 344 metres’ altitude, in the extreme north-west of Iraq.

There has been a Christian presence in Faysh Khabur for a very long time. One of the most tragic episodes in the history of Faysh Khabur took place on 11th July 1915. This day saw 937 martyrs exterminated by the death squads of the Kurdish Artouche tribe, whose crimes were perpetrated on order of the vali of Diyarbakır Rechid Bey. In Faysh Khabur this history is still fresh in people’s minds.

In February 2018, there were 130 Chaldean families living in Faysh Khabur. The Church of Our Lady of the Seeds in Faysh Khabur was built in 1861. It

was restored in 2005-2007. A primitive church was found during the restoration work, located to the north under the esplanade. Its style and the ceramic objects uncovered date it back to the 7thcentury.

Pic : The Chaldean church of Our Lady of the Seeds in Faysh Khabur. February 2018 © Pascal Maguesyan / MESOPOTAMIA

Location

The Church of Our Lady of the Seeds[1] in Faysh Khabur[2] is located at 37°04’27.7″N 42°22’33.3″E and 344 metres’ altitude. Faysh Khabur is located in the far north-west of Iraq in the Zakho district of the governorate of Dohuk-Nohadra in the autonomous region of Iraqi Kurdistan.

The confluence of the Khabur and the Tigris, 4 kilometres’ north of Faysh Khabur, constitutes a natural border between Iraq and Syria. Opposite the Iranian Faysh Khabur, on the other side of the river is the Syrian town of Khanik.

Faysh Khabur is also located 5 kilometres from the point at which three borders – Syrian, Turkish and Iraqi – converge. However, the Ibrahim Khalil border crossing to Turkey is located 22 kilometres east of Faysh Khabur.

Soothed by the waters of the Tigris and the Khabur where people have lived since ancient times and farmed the land, Faysh Khabur occupies a vital geographic, historic and strategic location.

_______

[1] The church is also known as Our Lady of the Harvest.

[2] Faysh Khabur, or Fēškābūr. The ancient Syriac form is Pēšābūr.

Fragments of Christian history

There has been a Christian presence in Faysh Khabur for a very long time. It is even mentioned in the Chronicle of Seert in a story probably dating from the 7th century at the time of the bishop Ezekiel. [1]

The ancient Christian history of Faysh Khabur is very similar to that of other villages of the area. A pre-existing Jewish presence and early evangelization under the influence of apostles Thomas, Addai (can also be the apostle Jude, also known as Thaddeus in the Gospel) and Mari. Throughout a 4th century full of vocations, the tradition relates many stories of martyrs persecuted by the Persian King Shapur II. Throughout this period, hermitages and primitive sanctuaries developed, in the very same places where Assyrian churches and monasteries were progressively raised. This is how the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East, known as the Church of the East was founded and developed.

Throughout the centuries and until the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the valleys and the mountains which edge this part of Mesopotamia were a place of fulfilment and protection for the Church of the East, on both sides of the modern Iraq-Turkey border where catholic missions flourished from the 17th century onwards with a surge in the 18th century. The 16th century schism in the Church of the East gave birth to the Chaldean church (Catholic, in communion with Rome) which became dominant in Iraqi Mesopotamia. Faysh Khabur also turned to the Chaldean church, but much later in the 19th century.

This community and denominational unity collapsed at the end of the 19th and start of the 20thcentury with the multiplication of raids committed by Kurdish tribes against Christian villages, the genocide of the Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans and Syriacs in the Ottoman empire from 1915 – 1918, and the subsequent break down of the empire.

_______

[1] In Assyrie chrétienne, vol.II, Jean-Maurice Fiey, 1965, p.697

Faysh Khabur, 1915

One of the most tragic episodes in the history of Faysh Khabur took place on 11th July 1915. This day saw 937 martyrs exterminated by the death squads of the Kurdish Artouche tribe, whose crimes were perpetrated on order of the vali of Diyarbakır Rechid Bey. In Faysh Khabur this history is still fresh in people’s minds, “Do you know about the Armenian genocide? It came right to our door. The pasha promised security! First of all, he took all the weapons. He had the children killed. The girls were taken and submitted to Islam (in the neighbouring village on the other side of the Khabur)… We all remember and we will always remember, because it was a collective experience, not an individual incident.” [1] Those who were not killed in Faysh Khabur went into exile. This account has been confirmed by witnesses and travellers from the time, in particular by the Dominican priest Jacques Rhétoré, “the son of Mesttô [Mohamed-Agha Artouchi] Naïf, “like a butcher” crossed the Tigris and attacked Peychabour (Faysh Khabur) by the sword. The mayor of this large village with one thousand two hundred inhabitants, Yaco, and Father Thomas [Chérine] had their throats slit by the son of Mesttô; nine hundred people were massacred, the remaining three hundred fled to Mar Yaco, Alcoche and Mosul, some to the Silopi Kurds.”[2]

_______

[1] Comments by Faès Gorgis, inhabitant and historian of Faysh Khabur, February 2008, in « Chrétiens d’Orient, ombres et lumières », Pascal Maguesyan, Éditions Thaddée, January 2014, p.279-280

[2] In “Les chrétiens aux bêtes”, Jacques Rhétoré, p.321. Study and presentation by Joseph Alichoran. Éditions du cerf (histoire), 2005.

Faysh Khabur, 1933

At the end of the first world war, the Assyrian Christians of Hakkari (Turkey) who survived the genocide of the Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans and Syriacs in the Ottoman Empire and who sought refuge in Mesopotamia under British rule, were used as combat troops, the Assyrian Levies, who helped to maintain order whilst hoping this would see them awarded political favours for the Assyrian Chaldean nation. “Rather than a State, the still-born treaty of Sèvres signed on 10 August 1920, signed between Turkey and associated allied powers, only afforded the Assyrian-Chaldeans guarantees and protection as part of a future autonomous Kurdistan. The treaty never came into force.”[1] The 6,500 Assyrians commanded by General Agha Petros could only count on themselves and attempted to take back Hakkari in October 1920 but this degenerated into a punitive and ultimately fruitless expedition. In 1923, the Lausanne treaty killed off the Assyrians’ and Armenians’ illusions of autonomous rule, simultaneously ruling out any chance of return. When the British mandate came to an end and Iraq became independent on 3rd October 1932, the Iraqi authorities wanted to disperse the Assyrian Chaldeans. The Assyrians refused and entered into resistance. A thousand of them took up arms and travelled to Syria which was under French rule at this time, passing though Faysh Khabur, in July 1933, with a view to negotiating the collective, long-term settlement of their community. When they returned to Iraq at the beginning of August, once again via Faysh Khabur, to collect their families, the Assyrian fighters were shot down by King Fayçal’s troops but they managed to defeat the Iraqi forces. This affront caused Iraqi troops to take their revenge against the Assyrian-Chaldean villagers of Semmel, close to Dohuk. The massacre began on 8th August 1933, with help from the Kurdish tribes. Three thousand men, women and children had been killed by 11th August. “The Arab officers and soldiers who committed these crimes were promoted and received a triumphant welcome in Mosul and Baghdad; their leaders, the Kurdish Colonel Baker Sedqi, was made a General.”[2]

_______

[1] In “Du génocide à la diaspora : les assyro-chaldéens au XXe siècle”, Joseph Alichoran, Article published in the review Istina, 1994, N°4, October-December, p.24

[2] In “Du génocide à la diaspora : les assyro-chaldéens au XXe siècle”, Joseph Alichoran, Article published in the review Istina, 1994, N°4, October-December, p.29

Faysh Khabur, 1961 - 2018

For the rest of the 20th century, Christian people had no respite. From 1961 to 1991, the repeated bombing and fighting between Kurdish separatists and the government in Bagdad led to constant population displacements, from the villages to the major towns and vice versa. This included the Christian communities and had a major impact on Christian heritage. Dozens of Christian villages on the Syrian, Turkish and Iranian borders were bombed and razed to the ground. “The most ancient churches, some over ten centuries old, were destroyed.”[1] In the governorate of Dohuk-Nohadra, where Faysh Khabur is situated, “if we say that if one hundred churches were blown up (the real figure is of course much higher) this would mean at least two hundred inscriptions would be lost.”[2] ISIS may not have reached Iraqi Kurdistan, but “the outcomes of the Saddam era were terrible for the Christian community in Kurdistan. The so-called protector of the Christians of Baghdad and Basra wiped out the Christian community in Kurdistan. Dozens of extremely ancient churches, rare evidence of the origins of Christianity, were destroyed.[3]

In the second half of the 1990s, after the Gulf war and the progressive emergence of an autonomous Kurdistan, the Christians of Kurdistan returned to their home towns and villages. This phenomenon intensified from 2003 onwards, with the fall of Saddam Hussein and the new wave of anti-Christian persecution by criminal and Islamicist groups. This is how the village of Faysh Khabur was repopulated with Chaldean families returning from Baghdad, Mosul and the Nineveh plain. Over 200 houses were built, as well as public facilities, with support from the regional government of Iraqi Kurdistan. The Church of Our Lady of the Seeds and the sanctuary of Saint Georges were restored.

_______

[1] In “Croissance”, 1995, Chris Kutschera. https://www.chris-kutschera.com/chretiens_irak.htm. It should be noted that the Beidar (Bidar) church was renovated and is again used for services.

[2] In “Recueil des inscriptions syriaques”, tome 2, Amir Harrak, Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres, 2010, p.533

[3] In “Le livre noir de Saddam Hussein”, Chris Kutschera, Oh Éditions, 2005, p.398

Evolution of the demographics in Faysh Khabur

In 1913, under the Ottoman Empire at a time when the Iraqi and Syrian states did not exist, Faysh Khabur was the largest village in the Chaldean diocese of Gezirah (Djezireh) with 1,300 inhabitants (Chaldean), two priests and a school[1]. The village was martyred during the genocide in July 1915, the survivors returned after the war, under British rule. During the 1957 census, the population of Faysh Khabur reached 899 inhabitants (Chaldean). Faysh Khabur was evacuated in 1974 in the midst of the Iraqi-Kurdish war, the villagers took refuge in Syria and returned a year later. The village was once again emptied in 1976 and the villagers transferred to Zakho when the Iraqi regime decided to create a strategic border dead zone, whilst undertaking the Arabisation of the whole region[2]. The Arab colonisers abandoned Faysh Khabur in 1991 at the end of the Gulf war and the creation of the autonomous Iraqi Kurdistan. At this point the village was occupied by Kurdish families (Muslim) and in 1998 only one elderly Christian couple remained in Faysh Khabur, the caretakers of the church of the Virgin Mary[3]. The Chaldeans only returned to Faysh Khabur after the fall of the Iraqi regime in 2003. Almost 220 Chaldean families returned to settle in their ancestral village as of 2005 whilst the Kurds left. In February 2018, there were 130 Chaldean families still living in Faysh Khabur[4]. At the same time large numbers of Yazidi families displaced from the Sindjar were living in survival conditions in a camp on the edge of the village.

_______

[1] In “L’Église chaldéenne catholique, autrefois et aujourd’hui” Abbé Joseph Tfinkdji, 1913, Extract from the Annuaire Pontifical Catholique from 1914, p.57

[2] In “Le livre noir de Saddam Hussein”, Chris Kutschera, Oh Éditions, 2005, p.395

[3] In “Recueil des inscriptions syriaques”, tome 2, Amir Harrak, Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres, Tome 1, p.538 + Tome 2 for the photos p.246

[4] Data collected by the MESOPOTAMIA mission on 18th February 2018, from Monsieur Faès Gorgis, Headmaster of the school in Faysh Khabur and historian.

History of the Church of Our Lady of the Seeds in Faysh Khabur

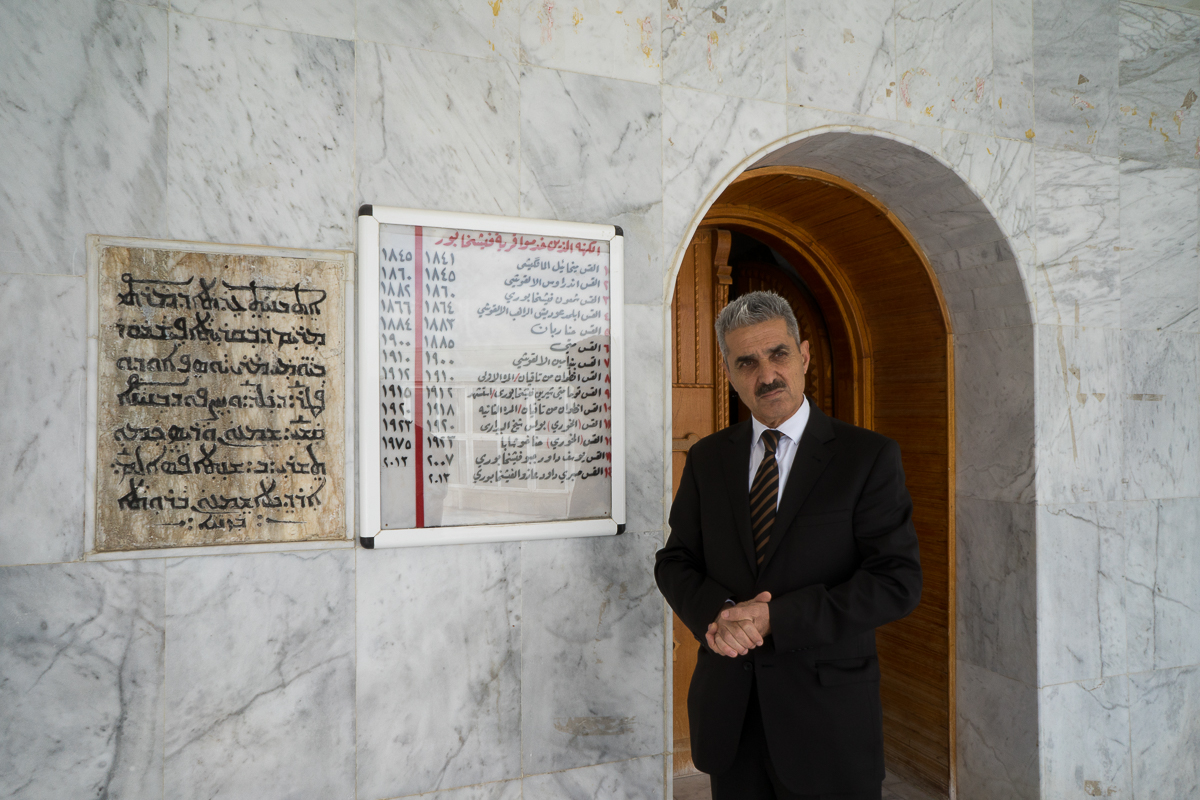

The Church of Our Lady of the Seeds in Faysh Khabur was built in 1861.[1] Two inscriptions testify to this, the most recent being a copy of the first original inscription which has been partially damaged. This 1861 inscription in Syriac Estrangela measuring 40/43 cm, shows that the church of Saint Mary was built in 1861 at the time of the Chaldean Patriarch Joseph VI Audo (1848 – 1878), Father Šem‘ōn and chief Kammo, by the architect Šem‘ōn Barūtā.[2]

The Church of Our Lady of the Seeds in Faysh Khabur underwent more than a mere renovation. It was fully restored in 2005-2007. Today almost none of the initial architecture and original materials used are recognisable.

_______

[1]The priest and linguist Albert Abouna, born in Faysh Khabur, documented the existance of the church of Our Lady of the Seeds.

[2] In “Recueil des inscriptions syriaques”, tome 2, Amir Harrak, Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres, Tome 1, p.538-539 + Tome 2 for the photos p. 246

Description of the Church of Our Lady of the Seeds in Faysh Khabur

Viewed from the outside, standing on a promontory overlooking the Tigris, the church of Our Lady of the Seeds in Faysh Khabur does not look like a religious building. The building is immense, almost cubic, entirely covered in marbled white-grey sandstone tiles and covered by a terrace roof. Only the bell tower in the south-east corner of the building inscribed with a large cross and with its small bell indicates that the building is a church.

The estate of the Church of Our Lady of the Seeds is closed off with a perimeter wall. It is accessed from the east. There are landscaped gardens either side of the central avenue. The esplanade to the north is covered with the same floor tiles as the building’s facade, the roof and the bell tower.

The interior of the church is accessed via the north side-aisle, using two doors under the gallery.

Viewed from the interior, thanks to the arches and pillars, it is possible to distinguish the structure made of jointed cut stones, partly covered in a white coating.

The architectural layout of this basilica church is composed of three naves and four bays. The central nave is mounted with a pointed barrel vault. The side aisles are connected to the central nave with thick pointed arches which support three pairs of freestanding, square-cut pillars.

The sanctuary is separated from the central nave by a large royal door with pointed arch. In the centre stands a grey marble high altar, mounted with a cupola, at the foot of which is a small jar containing the bones of martyrs from 1915. Either side of the high altar, there are side chapels each with their own altar. To the south, in the corner, is a small baptismal font.

A tribune for singers is located above the central nave, aligned with the sanctuary, against the west wall.

During the 2007 reconstruction, “three engraved stone plaques were uncovered. Each of them represents a disproportionate figure produced using the champlevé technique, inserted into a frame, standing, with a small head and long arms in the form of a cross.”[1] This figure could represent the crucified Christ. These plaques are embedded into the north-west wall of the church.

_______

[1] In « Notre Dame des Semences à Fišhabur et ses inscriptions syriaques », Narmen Ali Muhamad Amen, Salah-el-din University, Arbil (Kurdistan), Iraq. Cahiers d’études syriaques. 1. Geuthner, p. 297

Discovery of a primitive church

A primitive church in the form of a crypt, situated to the north of the esplanade, was discovered in 2007 during the restoration work on the Church of Our Lady of the Seeds. Accessed by a straight staircase, it is a single nave church with a series of three vaulted chambers. Its style and the ceramic objects uncovered date it back to the 7th century. Wine jars and bones were also found “Neither I nor my father knew this church existed” explained Faès Gorgis, a resident and historian of Faysh Khabur[1]. “We don’t know where the objects found by the workers are,” the historian explained regretfully. “They were entrusted to Father Youssef Daoud. We don’t know what he did with them.”

The existence of a very old shelter under the rock to the west is also of note, on the same level as the bed of the Tigris. In imitation of the grotto in Lourdes, the shelter was renovated and revamped in 2003 and fitted with an altar for services.

_______

[1] Interview with Faès Gorgis by the Mesopotamia team, 18th February 2018

Other churches in Faysh Khabur

On the outskirts of Faysh Khabur is a ruined church surrounded by a cemetery named Mar Gīwargīs (Saint George) where pilgrims came on 24th April, the day of the commemoration of the 1915 genocide.

A small sanctuary also named after Saint George, is located in the village of Faysh Khabur. Its date of foundation is unknown, however an engraved plaque in Syriac Estrangela indicates that it was renovated and completed in 1964.[1] Further renovation work was undertaken when the Chaldean inhabitants of Faysh Khabur returned to the village in 2005.

_______

[1] In “Recueil des inscriptions syriaques”, tome 2, Amir Harrak, Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres, p.539

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute