The Church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Aqrah

The Ancient Church of the East church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus (Mar Sarkis & Bakhos) is located at 36°43’27.4″N 43°52’25.7″E and at 632 metres altitude in the lower part of the city of Aqrah.

The region of Aqrah, also known as the Margā province, was home to the largest monasteries of the Church of the East. All of which have now disappeared.

The church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus, in the lower part of the city of Aqrah, is a relatively new building of no particular architectural interest. It is a two-storey rectangular building made of reinforced concrete.

The property of the Ancient Church of the East, the church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Aqrah is also open to Chaldean Christians.

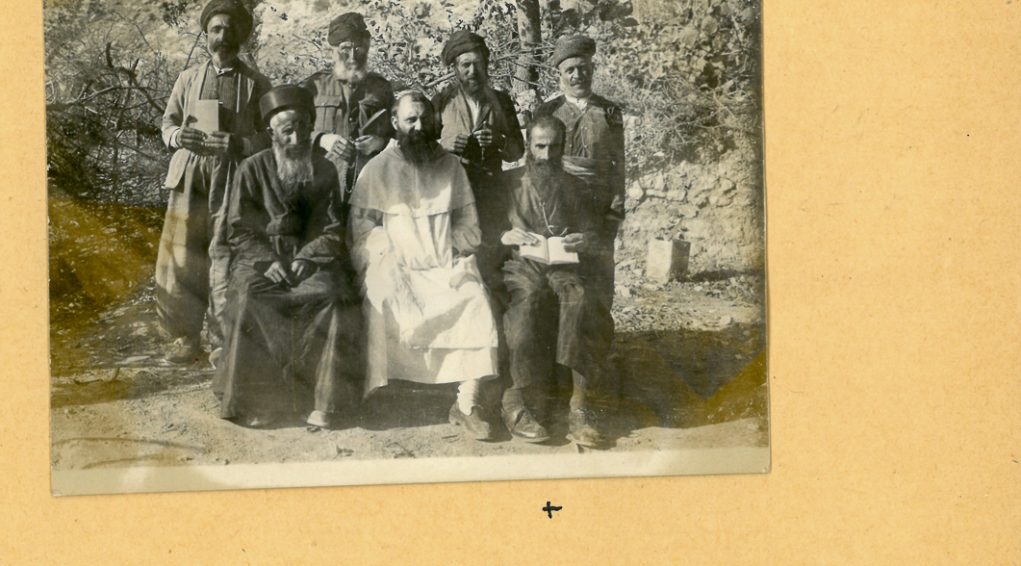

Pic : In front of the entrance gate to the Assyrian church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Aqrah. July 2017 © Pascal Maguesyan / MESOPOTAMIA

Location

The church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus is located at 36°43’27.4″N 43°52’25.7″E and at 632 metres altitude in the lower part of the city of Aqrah.

Aqrah[1], to the west of Great Zab backs onto the mountain range of Chindar which borders Iraqi Kurdistan. The city is also 96 km to the east of Dohuk-Nohadra and 80 km north of Erbil.

Aqrah is an extremely ancient city, built on the terraces in the cliff face which overlooks the ancient citadel destroyed in 1840. There are also numerous gardens and waterfalls, as well as ancient traditional houses built of stone and earth.

_______

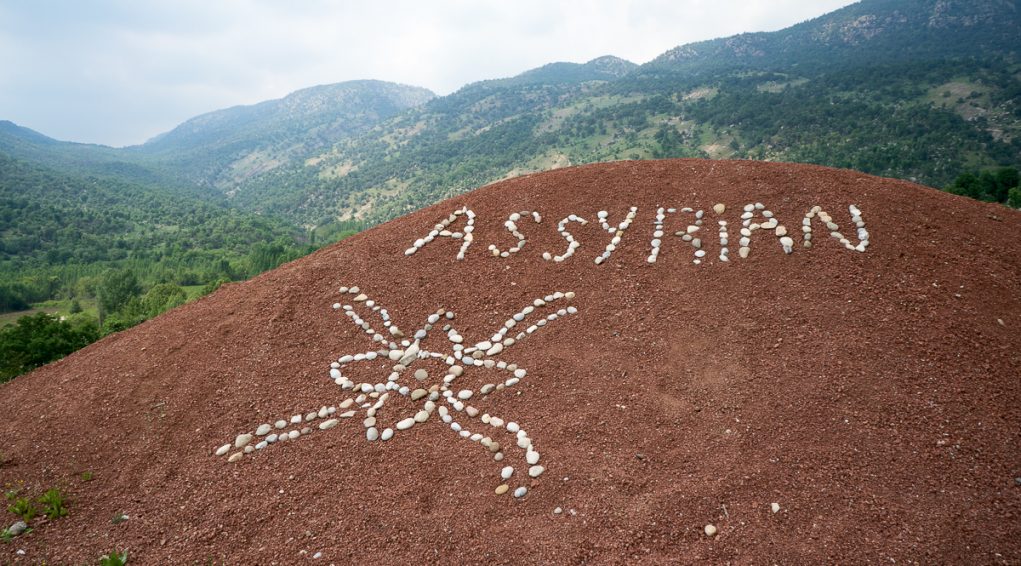

The names of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East

The Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East is known by several names. Here we will simply mention the “Church of the East” in opposition to the Church of the West; “Church of Assyria” and “Church of Meopotamia” which identify its members with these ancient civilisations; “Church of Persia”, as it was under the eponymous Empire that the Eastern Christians structured their geopolitical space and that so many were martyred; and the “Nestorian Church” as it was established by consent with the Christology of the patriarch of Constantinople Nestorius deposed at the Council of Ephesus in 431.

The official denomination Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East is the most complete. Founded and legitimised by the apostle Thomas, the church is proud of its roots in ancient times and places an emphasis on its missionary work.

The name “Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East” was the result of a division dating from 1964 based on the choice of calendar: Gregorian or Julian. The vast majority of Assyrians chose to use the Gregorian calendar, in communion with the other Christians in the region. Those who remained faithful to the Julian calendar formed the Ancient Holy Apostolic Catholic Church of the East. This separation did not alter the sense of belonging to one and the same Church.

Origins of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East

According to the tradition, the origin of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East goes back to the apostles and disciples like Thomas, Addai (some assert that Addai is also the disciple Thaddeus, also known as Jude) and Mari. The tradition also recounts that Thomas “stopped in Seleucia-Ctesiphon during his journey to India.” [1]

The new religion would have been preached specifically to local Jewish communities. “It is not known which communities were evangelised, but it is reasonable to assume that the first converts were members of the Jewish community which was predominant throughout Mesopotamia, and even beyond the Tigris, since the deportation of Babylon under Nabuchodonosor. Most likely the greatest efforts to convert people were focused on these Jewish communities, as it already was the case in all cities of the Roman Empire.”[2]

It was really from the 4th century on that the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East started structuring itself in Seleucia-Ctesiphon and almost simultaneously the Persian King Shapur II ushered in an era of anti-Christian persecution, resulting in large numbers of martyrs who are still worshipped centuries later.

In the 5th century, the conflict between the Roman Empire and the Persian Empire, along with Christological disputes between schools of theology, widened the gap between the Churches of the West and the East. After having rejected the conclusions of the Council of Ephesus (431) and welcomed in the patriarch Nestorius, the Church of the East confirmed its break with Rome and Constantinople and asserted its autocephalous nature. This was the second act in the birth of the Church of the East, after it was founded by Saint Thomas.

_______

[1]In Histoire de l’Église de l’Orient, Raymond le Coz, Éditions du Cerf, 1995, p.21

[2]InHistoire de l’Église de l’Orient, Raymond le Coz, Éditions du Cerf, 1995, p.22

Monastic influence and achievements

Throughout the centuries, the high plateaus and mountains of Mesopotamia (south-east of Turkey and Iraqi Kurdistan), formerly difficult to access, were a place where the Church of the East flourished and found refuge. The region of Margā (north of Iraq, the region of Aqrah), was home to some of the most influential monasteries of the Church of the East, such as the Rabban Bar ‘Idtā monastery, as well as the Mar Ya’qōb de Bet‘Ābe (Beth’ Abhé)[1]the history of which was written by the illustrious 4th century monk and bishop Thomas de Marga, and which we know was built at the end of the 6th century at the latest. Thanks to the The Book of Governorsby Thomas of Marga there is a rich vein of historic documentation on the Church of the East between the 6th and 9th centuries[2]. In the 9th century there were more than twenty monasteries in the province of Marga. At the start of the 17th century, only four monasteries were mentioned in the region of Aqrah, with around sixty Church of the East Christian villages.

The Syriac-Orthodox church also laid roots in these mountains to the north of Mesopotamia in the 4th and 5th centuries. It developed a vast network of monasteries around the Mar Matta monastery on mount Maqlūb, which is said to have been home to thousands of monks and was known as the “Mountains of Thousands”.

_______

[1]This monastery is next to Aqrah.At the end of the 19th century, the geographer Vital Cuinet saw only a few ruins. See “La Turquie d’Asie. Géographie administrative. Statistique descriptive et raisonnée de chaque province de l’Asie-mineure », second tome. Ernest Leroux publisher, Paris, 1891, p.844-845.

[2]In “The ecclesiastical organisation of the church of the east, 1318 – 1913”, David Wilmshurst, Éditions Peeters (Louvain), 2000, p.155

Fragments of history: the Assyrians from the 16th to the 21st century

In the 16th century, the schism within the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East, engendered the Chaldean Church (in communion with Rome) and caused a major upheaval The majority of Christians in the Apostle Assyrian Church of the East progressively turned to the Chaldean Catholic Church, The consequences of this schism were such that the great Church of the East of the first centuries became “at the end of the Middle Ages, a mere Church-nation”[1], isolated in the mountainous border regions of the Persian (north-west Iran) and Ottoman (extreme south-east of Turkey and north of Iraq) Empires.

Under the Ottoman domination through the 19th century, Kurdish tribes pillaged Christian villages, killing and kidnapping the inhabitants. In 1843 – 1847 the massacres committed were truly horrendous: “The Kurdish Emir of Bohtan Béder-Khan butchered the Assyrians and Chaldeans in the province of Van. Over 10,000 men were massacred, thousands of women and young girls kidnapped and forced to convert to Islam, all the Assyrians and Chaldeans possessions and villages were burned to the ground.[2]”In 1894-1896 the nature of the massacres of the Christians (Armenians, Assyrians, Chaldeans and Syriacs) changed. These were organised at the highest levels of the empire by Sultan Abdul Hamid II, known as the Red Sultan, who sent out his hamidiyéto attack Christian locations. This genocide left the Christian communities almost wiped out of existence.

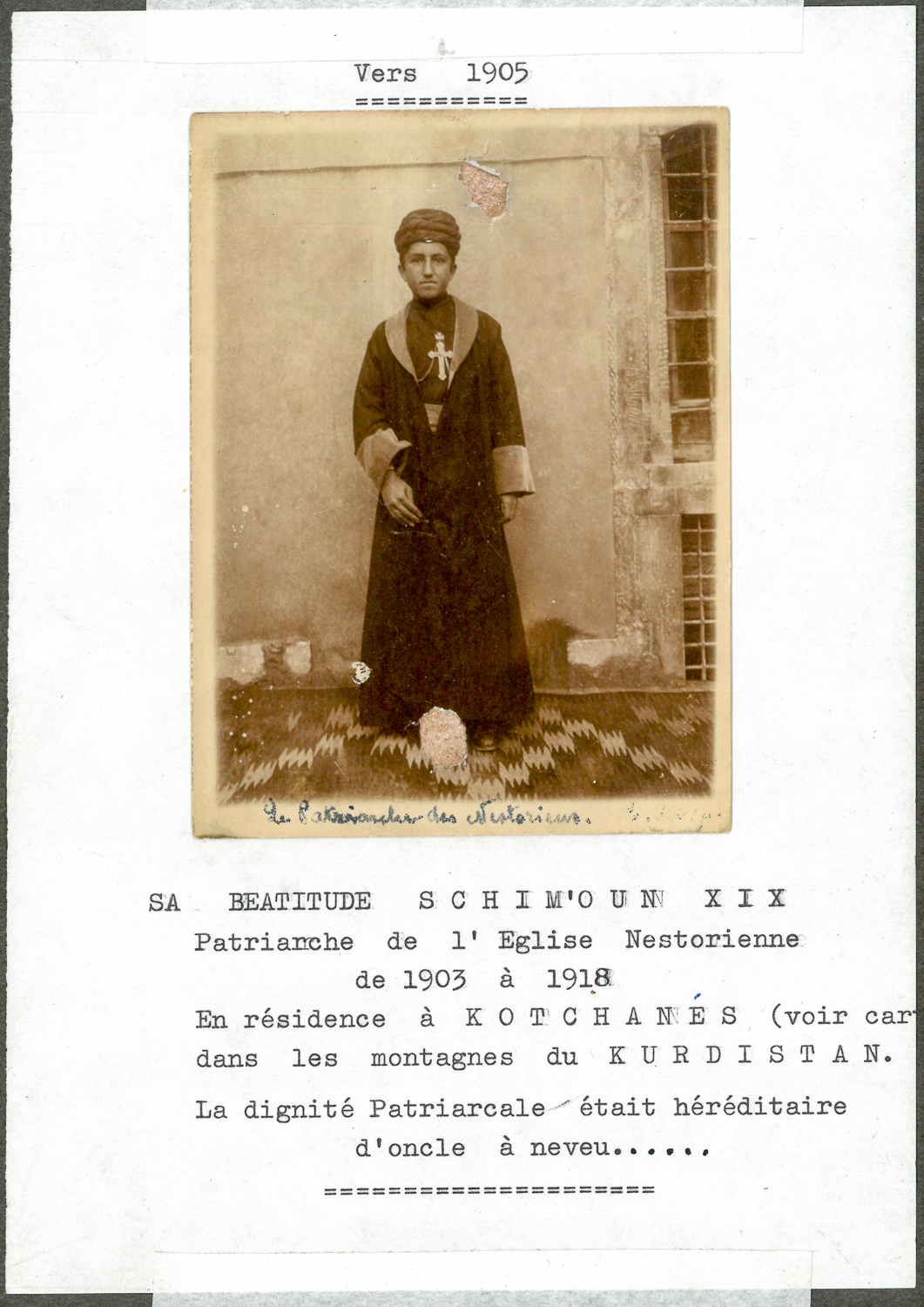

When the nationalist Young-Turkrevolution overthrew the Sultan in 1908, Christians in the Empire were filled with the desperate hope of a change in fortunes. This was illusory. As of 1909, the Adana massacres constituted the prelude to the systematic, planned destruction of the Christian communities, carried out under the cover of the First World War from 1915 – 1917. From the very start of the war, in the autumn of 1914, Turkish and Kurdish troops entered into Persia and massacred the Assyrian and Chaldean communities in the Ourmiah district. In April 1915, when the genocide of the Armenians began in the eastern provinces of the Ottoman Empire, 150,000 Assyrian survivors grouped together in the Hakkari mountains (extreme south-east of Turkey) from the vilayetof Van around the patriarchal seat of Kotchanes[3](since 1662), residence of the Catholicos Mar Schemoun “member of the family of the same name, guarantor of the traditions and nepotism exercised within it since 1450”[4]. The Hakkari Assyrians resisted their Turkish and Kurdish attackers ferociously, but were forced into exodus into Persia. “They crossed the high mountains towards Salamas in Iran on 7 – 8 October 1915. The survivors, 50,000 out of 100,000 arrived exhausted[5]. They were taken in by the Russian army and their compatriots (…) But the local population was against them and their compatriots living there were ruined.” From 1915 to 1917, the massacres of the Armenians, Syriacs, Chaldeans and Assyrians continued and intensified, spreading to all the towns and villages in the Ottoman provinces of Van, Bitlis, Mamuretulaziz, Erzeroum, Diyabakir et Aleppo. These horrific massacres led to a mass exodus which killed even more people as they headed for the deserts of Syria and Mesopotamia. During the summer of 1918, abandoned by their Russian protectors “around eighty thousand Assyrians and Chaldeans, with their cattle and their belongings[6]”once again took to the road from Ourmiah, towards Hamadan in Persia, before finally arriving in Mesopotamia in Bakouba (50 km north-east of Baghdad). Half of the displaced population perished during this further ordeal.

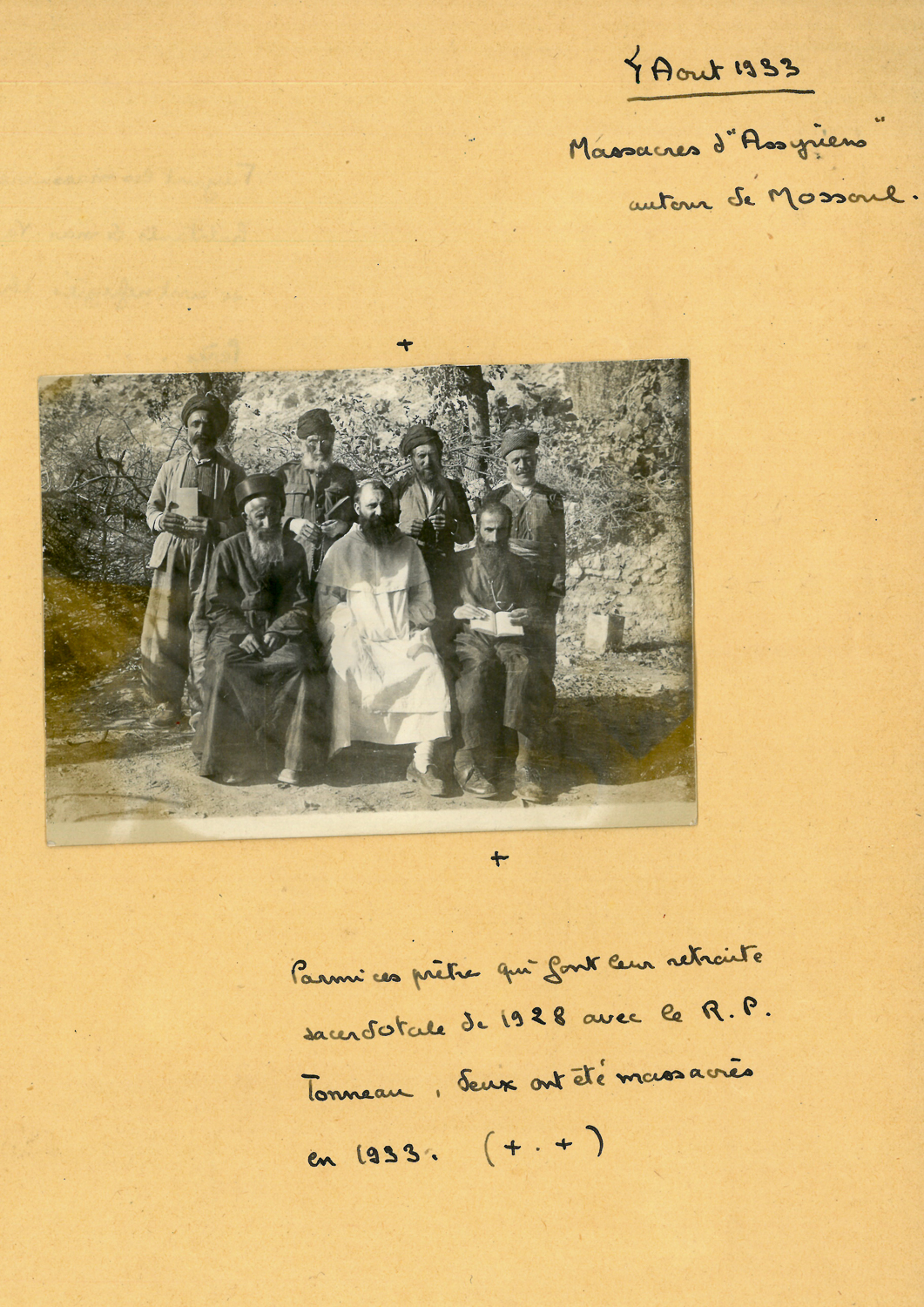

In Mesopotamia under British rule, the Assyrians were used as combat troops, the Assyrian Levies,who helped to maintain order whilst hoping this would see them awarded political favours for the Assyrian Chaldean nation. “Rather than a State, the still-born treaty of Sèvres signed on 10 August 1920, signed between Turkey and associated allied powers, only afforded the Assyrian-Chaldeans guarantees and protection as part of a future autonomous Kurdistan. The treaty never came into force.”[7]The 6,500 Assyrians commanded by General Agha Petros could only count on themselves and attempted to take back Hakkari in October 1920 but this degenerated into a punitive and ultimately fruitless expedition. In 1923, the Lausanne treaty killed off the Assyrians and Armenians illusions of autonomous rule, simultaneously ruling out any chance of return. When the British mandate came to an end and Iraq became independent on 3 October 1932, the Iraqi authorities wanted to disperse the Assyrian Chaldeans. The Assyrians refused and entered into resistance. A thousand of them took up arms and travelled to Syria which was under French rule at this time, in July 1933, with a view to negotiating the collective, long-term settlement of their community. When they returned to Iraq at the beginning of August, via the village of Feshkhabour to collect their families, the Assyrian fighters were shot down by King Faisal’s troops but they managed to defeat the Iraqi forces. This affront caused Iraqi troops to take their revenge against the Assyrian-Chaldaen villagers of Simele, close to Dohuk. The massacre began on 8 August 1933, with help from the Kurdish tribes. Three thousand men, women and children had been killed by 11th August. “The Arab officers and soldiers who committed these crimes were promoted and received a triumphant welcome in Mosul and Baghdad; their leaders, the Kurdish Colonel Baker Sedqi, was made a General.”[8]

The rest of the 20th century was not much better for the Assyrian-Chaldeans. During the Second World War, new Assyrian combat units contributed to the British war effort against an Iraqi government supported by Nazi Germany. They obtained no diplomatic rewards.

As of 1961, and up until 2003, the successive civil wars opposing Kurdish separatists and the Baghdad government had an appalling effect on the Assyrian-Chaldean Christian communities in the north of the country: killings, blackmail, destruction of heritage, forced population displacements, forced Arabisation, gas attacks etc.

In 2003, end of the tyrannical regime of Saddam Hussein, marked the start of a chaotic period of Islamism and organised crime, during which criminal groups such as Al-Quaeda and ISIS persecuted Christian communities. Against all expectations, in the Kurdish mountains, the Assyrians and other Christians of Iraq benefited from a historic period of respite, thanks to the benevolence of the Kurdish regional government which implemented policy favouring the reinstallation of native-speaking Christian communities. The Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East can finally look to the future.

_______

[1]In “Du génocide à la diaspora : les assyro-chaldéens au XXesiècle”, Joseph Alichoran, Article published in the review Istina, 1994, N°4, October-December, p.4

[2]Eugène Griselle in “Qui s’en souviendra ? 1915 :le génocide assyro-chaldéo-syriaque.”, Joseph Yacoub, Les éditions du Cerf,, p.128

[3]In 1988, nothing remained of this patriarcate other than the patriarchal church Mar Shallita, built in 1689 and in poor condition. What remains in 2018? Source Joseph Alichoran.

[4]In “Du génocide à la diaspora : les assyro-chaldéens au XXesiècle”, Joseph Alichoran, Article published in the review Istina, 1994, N°4, October-December, p.5

[5]In “Qui s’en souviendra ? 1915 :le génocide assyro-chaldéo-syriaque.”, Joseph Yacoub, Les éditions du Cerf,, p.128

[6]In “Du génocide à la diaspora : les assyro-chaldéens au XXe siècle”, Joseph Alichoran, Article published in the review Istina, 1994, N°4, October-December, p.22

[7]In “Du génocide à la diaspora : les assyro-chaldéens au XXesiècle”, Joseph Alichoran, Article published in the review Istina, 1994, N°4, October-December, p.24

[8]In “Du génocide à la diaspora : les assyro-chaldéens au XXesiècle”, Joseph Alichoran, Article published in the review Istina, 1994, N°4, October-December, p.29

Assyrian Christian demographics in Iraq

At the end of the 19th century and on the eve of the First World War, the Assyrian nation was estimated at one million people in Iraq, Iran and Turkey. In 1957, there were 750,000 to 1 million in Iraq. At the start of the 1970s, this figure fell to 300,000. In 2017, there were less than 40,000. This demographic collapse is the consequence of a series of historic disasters.

The main Assyrian populations in Iraq are found in Dohuk-Nohadra where there are 2,000 families. Around Dohuk-Nohadra, in the districts of Barwar, Semel, Zakho and Amadia, there are 1,500 families spread across 55 villages. In total, the province of Dohuk-Nohadra is home to around 20,000 Assyrians.[1]

Four major monasteries of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East remain: Mar Odicho’ in Dere, Mar Qayouma in Kani Massi Doure, Mar Gewarguis in Kani Massi Iyed and Mar Mouche in Kani Massi Tchelek.

_______

[1]Source: Khoury Philippos, archpriest of the Mar Narsaï church in Dohuk-Nohadra part of the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East.

Christian demographics of Aqrah

At the end of the 19th century, from 1890-1891, there were 4,700 inhabitants in Aqrah, including 4,150 Muslims, 300 Israelites[1]and 250 Christians (Chaldeans and Jacobites[2]). The Chaldeans had small school of 15 pupils: “The schools in the mountains are the most basic facilities you can imagine. The schoolhouse is the church. The children sit along the wall, on mats and the teacher stands in the middle.”[3] The Syriac-Orthodox had no school and no priest.

Beyond the city limits, in the cazaof Aqrah, there were 81 villages for 11,000 inhabitants: 10,150 Muslim Kurds, 550 Chaldean and Syriac-Catholic Christians and 300 Israelites.

In 1913, the demographics had hardly changed. In Aqrah there was still a Christian community of 250 people (mainly Chaldean), with two priests, a church and a school[4]. This statistic was the same in 1961[5]before the start of the war between the Kurds and the government in Baghdad. The Christians in Aqrah, temporarily left the city in 1963 under the fire of the invading Arab forces. They were joined in the 1980s by Assyrian Christian families from the high plateaus of Nahla, whose 7 villages were destroyed and burned by Saddam Hussein. Sixty-five Assyrian families from the Nahla valley were still living in Aqrah[6]in 2017, compared to 250 in 1988.

At the start of the 21st century, a new Christian community formed in Aqrah made up of the displaced people from the Nineveh plain who arrived in August 2014, fleeing the ISIS offensive. Of the 500 – 600 displaced families, only 100 remained in July 2017. This figure will no doubt have continued to decrease as families return to their homes, freed and rehabilitated.

_______

[1]Israelite was the name used to designate Jews at this time.

[2]The Jacobites are part of the Syriac-Orthodox church.

[3]See “La Turquie d’Asie. Géographie administrative. Statistique descriptive et raisonnée de chaque province de l’Asie-mineure », second tome, Vital Cuinet. Ernest Leroux publisher, Paris, 1891, p.843.

[4]In L’Église chaldéenne catholique, autrefois et aujourd’hui,Abbé Joseph Tfinkdji, 1913, Extract from the Annuaire Pontifical Catholique from 1914, p. 51

[5]In “Assyrie Chrétienne”, vol II, Imprimerie catholique de Beyrtouth, J.M.Fiey, 1965, p.266

[6]Data collected on 22 July 2017 in Aqrah by the Mesopotamia team.

History and description of the church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Aqrah

The church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus, in the lower part of the city of Aqrah, is a relatively new building of no particular architectural interest. It is a two-storey rectangular building made of reinforced concrete. On the ground floor is a large community hall. The actual church on the first floor also resembles a large hall. Charmless and unadorned, it has a royal door composed of the three accesses to the sanctuary. There are no inscriptions or engravings. From the exterior, the only distinguishing feature is the bell tower on the roof. In front of the building, a garden has been created with a fountain in the middle and a cave dedicated to the Virgin Mary in the corner. The space is closed off by a perimeter wall with an entrance porch mounted with a small wooden cross.

The property of the Ancient Church of the East, the church of Saints Sergius and Bacchus in Aqrah is also open to Chaldean Christians.

Testimony

Benjamin Yalda Icho, 64 years old, is originally from the Assyrian village of Hizanke in the Nahla valley. Driven out of his village which was burned to the ground by Saddam Hussein’s forces in 1988, he was forced to settle in Aqrah with his family, where he still lives today: “There used to be 23 Assyrian Christian villages in the Nahla valley. Only seven remain: upper and lower Hizanke, upper and lower Chole, Belmande, Khelélane, Kchkava, Meroke, Chamra-Badke.”

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute