The Armenian Apostolic Church Sourp Sarkis in Havresk

The Armenian Apostolic Church Sourp Sarkis is located at 36°53’52.2″N 42°42’37.4″E and 445 metres altitude, in Havresk, a village rebuilt in 2006 for the Armenian community.

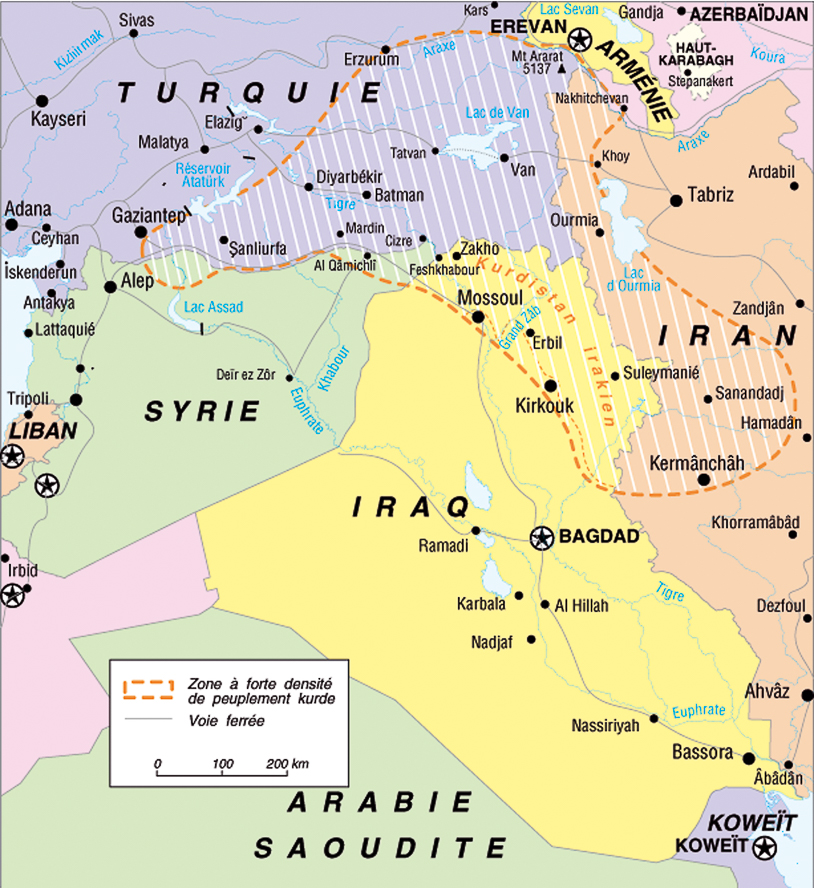

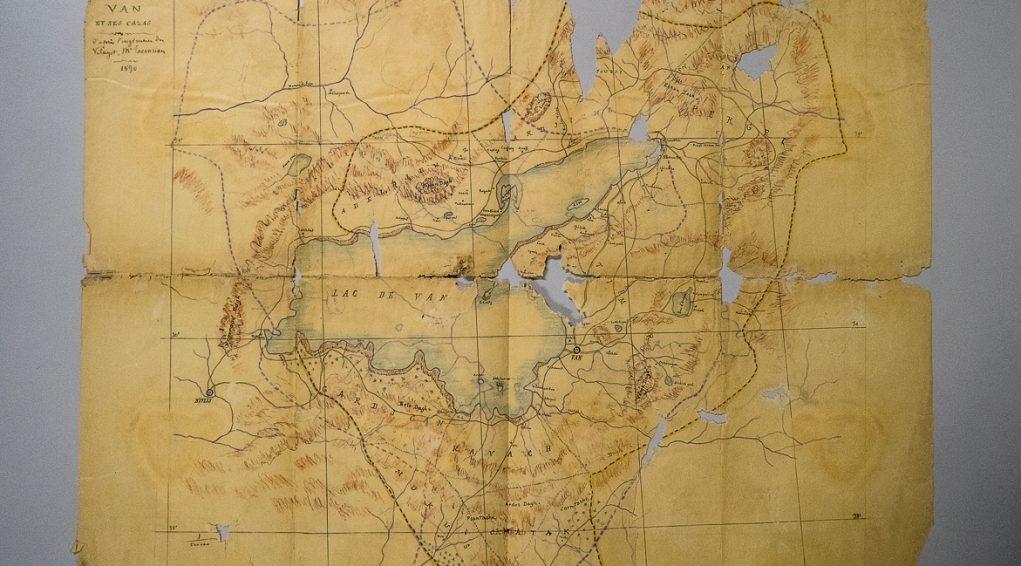

The history of the village of Havresk is directly linked to the genocide of the Armenians in 1915 – 1917. Large numbers of survivors in the Bakouba camp were re-settled close to the Iraqi border in the area around Zakho. Eleven Armenian villages like this were created in the 1920s and 1930s, Havresk, the largest of these, was built in 1927-1928. Five hundred families followed Levon Pacha Shaghoyan, an Armenian general who took part in Van’s resistance against the Turks, to Havresk. Levon Pacha Shaghoyan turned Havresk into a dynamic farming village.

In 1975, after the Kurdish rebels led by Mustafa Barzani were defeated, Saddam Hussein decided to Arabise the entire region. He had Havresk evacuated and destroyed. After the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, the Armenian families from Havresk decided to return in 2006. The new Sourp Sarkis church was built in 2010.

Pic : The Sourp Sarkis Armenian Apostolic Church in Havresk. August 2017 © Pascal Maguesyan / MESOPOTAMIA

Location

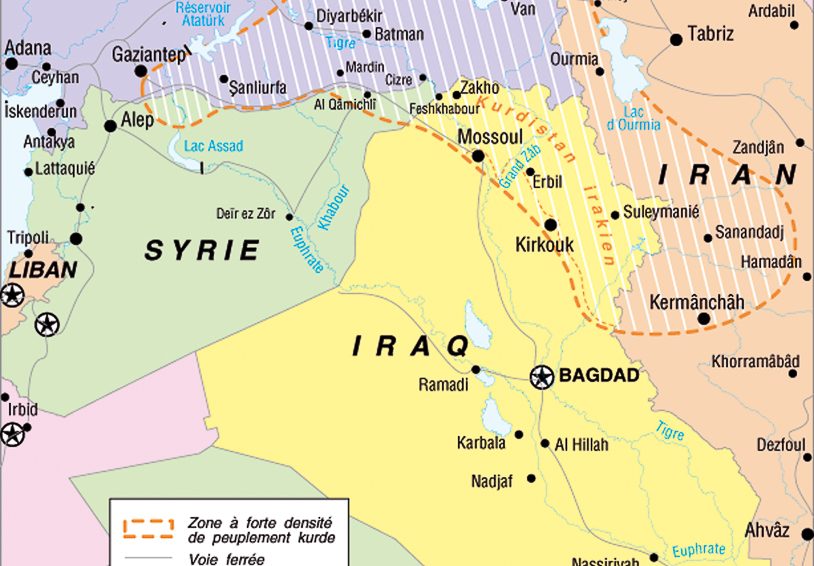

The Armenian Apostolic Church Sourp Sarkis is located at 36°53’52.2″N 42°42’37.4″E and 445 metres altitude, in Havresk, 30 km to the west of Dohuk-Nohadra, 90 km to the north-west of Mosul, 170 km north-west of Erbil and 52 km south-east of the border between Turkey and Syria.

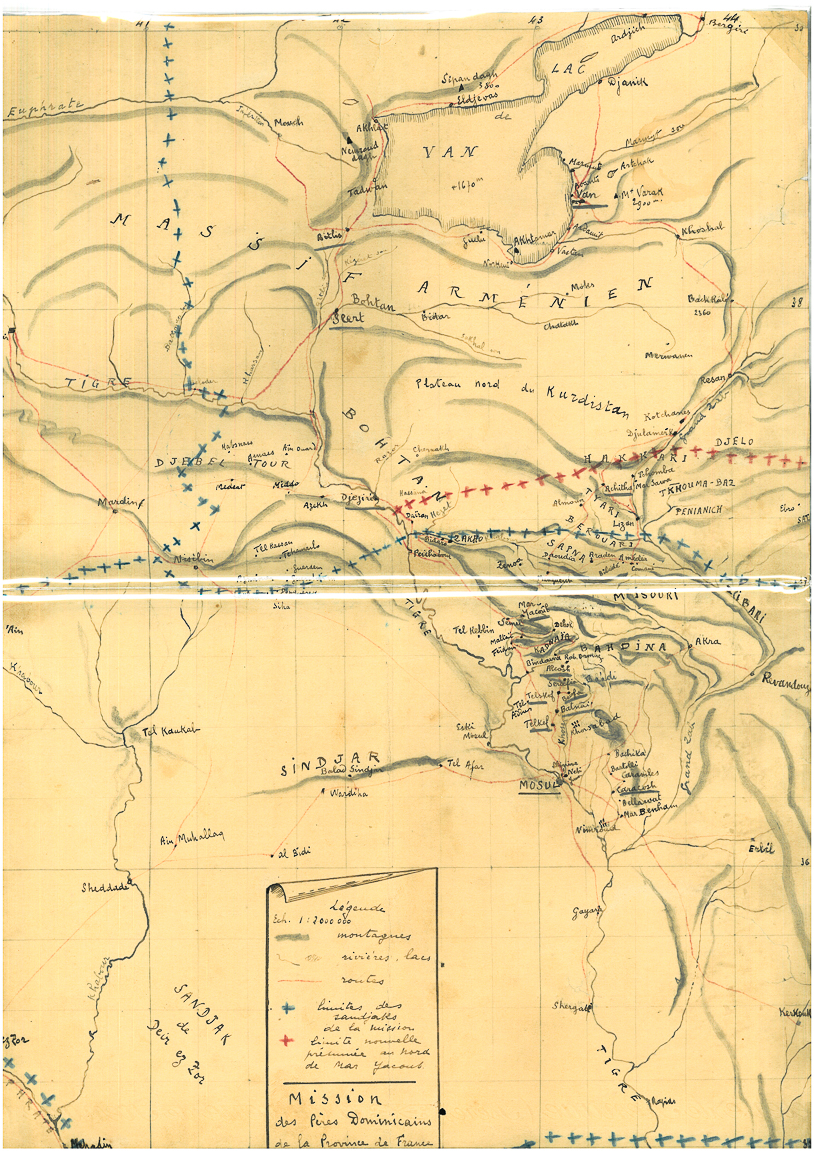

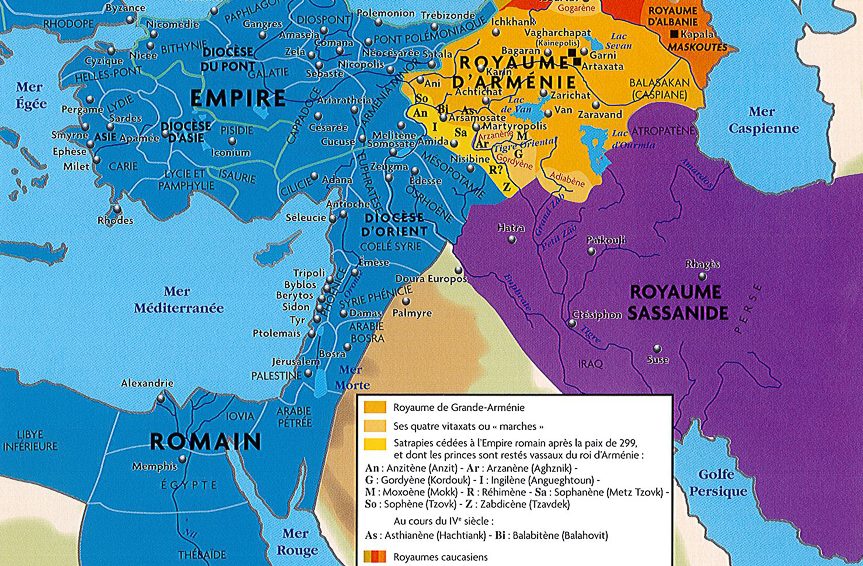

Origins of the Armenian presence in Iraq

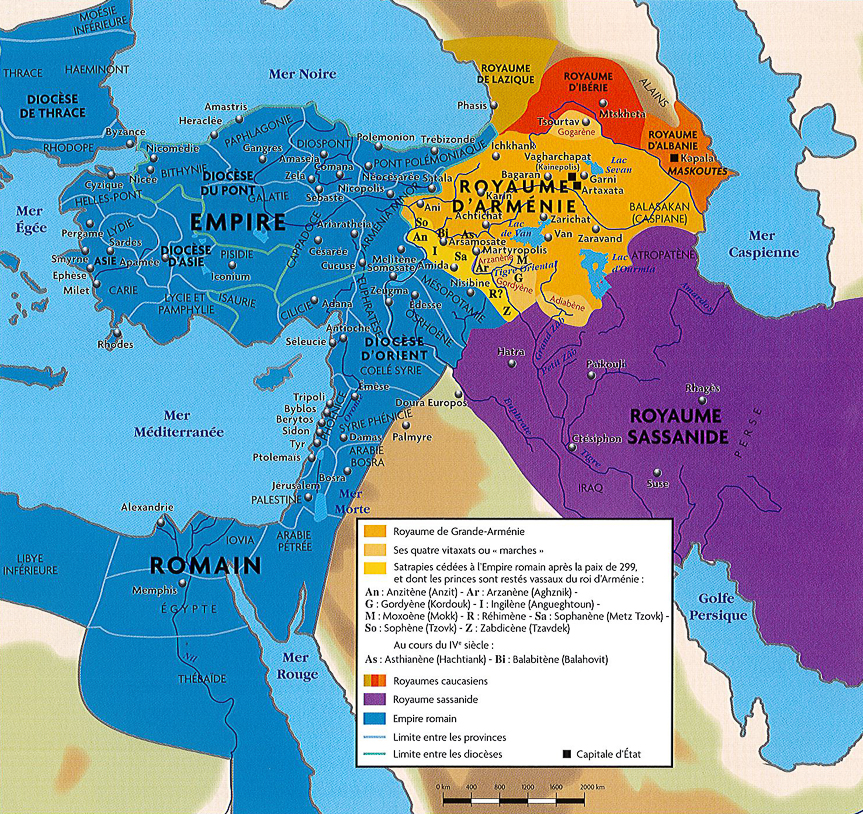

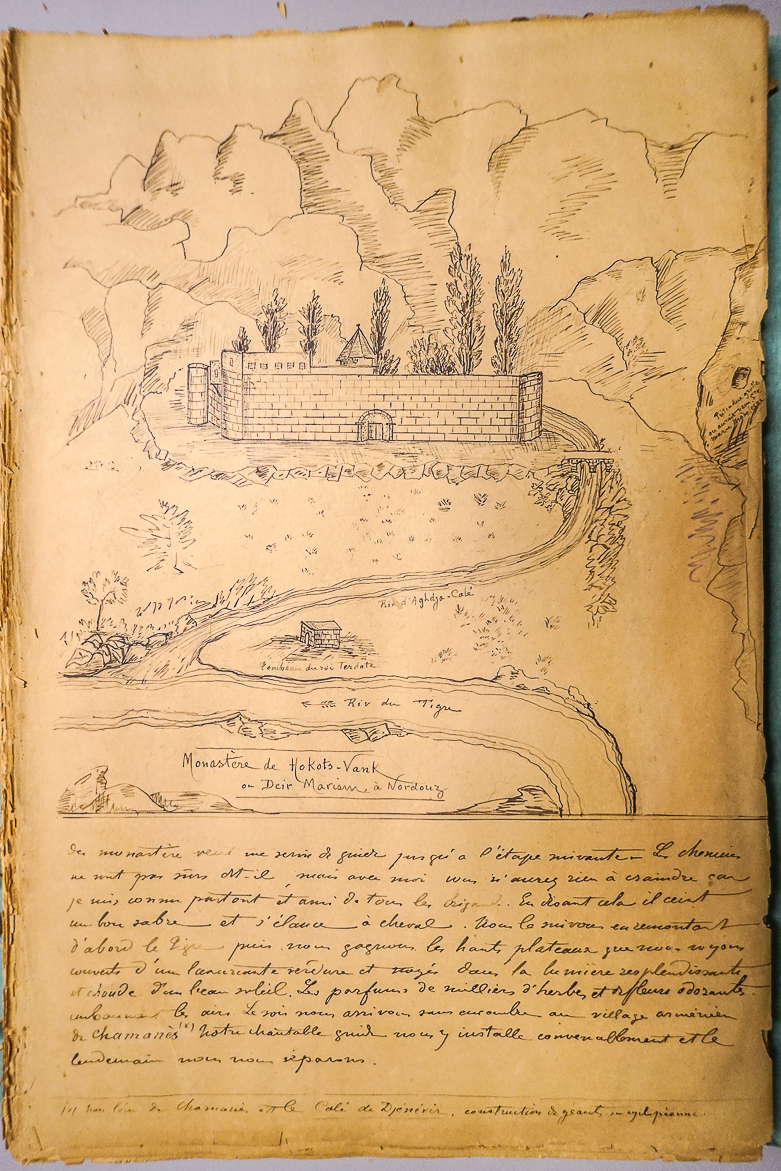

The origins of an Armenian presence in Mesopotamia have come along for centuries since Antiquity. In the 1st century BC, the Adiabene kingdom (with Arbeles/Erbil as “capital city”) was part of the Armenian Kingdom of Tigranes II the Great. At the very beginning of the 4th century, the area of Abadiene, which was then the most southern territory of the kingdom of Armenia, became the very first Christian “state” in History, around 301. “What also seems reliable is that there has been a meeting, around 328-329, between the only two Christian sovereigns in those times: the Roman emperor Constantine I and the Armenian Tiridates III. Constantine I confirmed the role of Tiridates III in the evangelisation of the East. In this way, the Armenian missionaries participated in the evangeliastion of Mesopotamia and the Sassinid kingdom, as recounted by the Greek historian Sozomene, in around 402: “then amongst the neighbouring peoples, the belief progressed and grew in large numbers and I think that the Persians became Christians thanks to the relationships they had with the people of Osroene[1]and Armenia (…)”.[2]

In the 17th century, new Armenian communities settled in Iraqi Mesopotamia after the Persian Shah Abbas I conquered Baghdad in 1623. In the early years of the 17th century, the Persian king forced the Armenian population of Julfa (former Armenian city in the Nakhichevan, on the northern bank of the Aras river) to exile. 12,000 Armenian people were then moved to New Julfa (Nor Djougha), at the gates of Isfahan, to take part in the development of the Safavid-Persian Empire’s new capital city. After Shah Abas died, the Armenians from Persian endured times of troubles. Lots of them moved to Mesopotamia and settled in Basra (south of modern day Iraq), whereas others set off to India.

When the Ottoman Sultan Murad IV regained control over Baghdad in 1638 with the help of Armenian Ottoman soldiers and a new phase started for an Armenian settling in Baghdad. All along the Ottoman domination’s period and until the fall of the Empire at the beginning of the 20th century, the Armenians developed their institutions so much that by the end of the 19th century they were nearly 90,000 living in Iraq.[3]

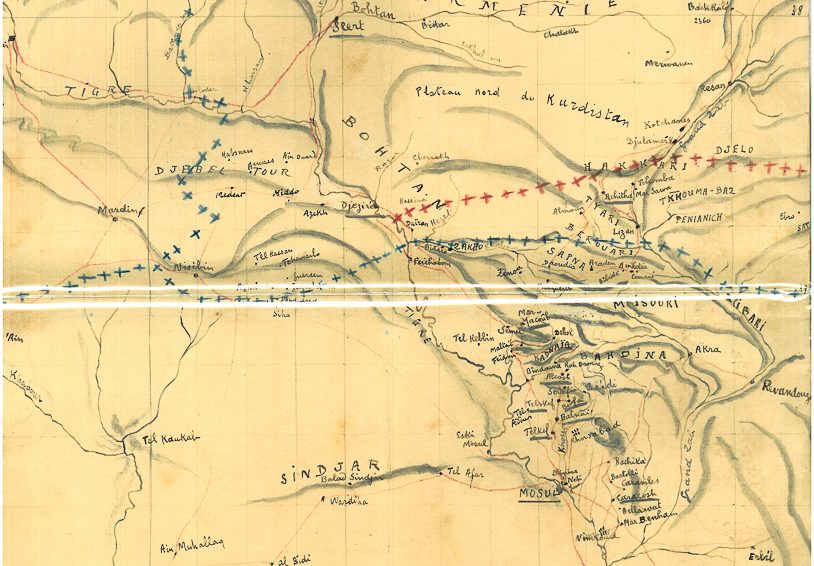

The genocide of the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire in 1915-17 was the last and terrible reason of their migration towards Iraqi Mesopotamia. Deported from the eastern provinces of the Empire, coming from the North (Diyarbekir) along the Tigris river, from the West (Ras-al-Ain) along the railway from Aleppo to Baghdad, or also from Van and then coming first through Persia, the Armenians arrived in some relegation areas such as Zakho, Havresk, Avzrog but also Kirkurk, Bakouba and Mosul. At this time a particularly tragic incident took place. In January 1916 over just two nights, 15,000 Armenian deportees living in Mosul and the surrouding area were exterminated, tied together in groups of ten and thrown into the Tigris river. Already, well before this carnage, on 10th June 1915, the German consul to Mosul, Holstein, telegraphed his Ambassador, reporting telling scenes

“614 Armenians (men, women and children) expulsed from Diarbekyr and transported to Mosul, were all killed en route, as they were transported by raft (on the Tigris). The kelek arrived empty yesterday. For a few days now the river has been carrying corpses and human limbs (…)” [4]

Nowadays, the Armenians in Iraq mostly descend from people who survived the 1915 genocide. Rather discreet on the political scene, they were known for being loyal and developed their own educational, social and religious infrastructure.

From a religious point of view, the Armenians from Iraq are mostly members of the Armenian Apostolic Church (autocephalous church since its origin in 301), some are members of the Catholic community[5]and some others joined a small evangelic community.

After Saddam Hussein’s regime fell in 2003, the situation worsened considerably. The attacks from Islamic and Mafia groups against Iraqi Christians also targeted the Armenians and their churches. On August 1st 2004, the Armenian Catholic church Our Lady of the Rosary, in Baghdad, Karada district, was struck by a bomb attack. An Armenian church under construction was also targeted on December 4th 2004. For nearly 20 years, these successive spates of violence set the tempo for Iraqi Armenians’ mass exodus. The battle of Mosul over the summer 2017 and the bombing intensity also affected the Armenian heritage. Before 2003, there were probably more than 25 000 Armenians in Iraq, whereas today the community leaders assert there are 10 000 to 13 000 Armenians still living in Iraq. Half of them are said to be living in Baghdad. The remainder live in Iraqi Kurdistan, Kirkuk, Sulaymaniyah, as well as Basra. There are no more Armenians in Mosul.

_______

[1]The people of Osroene were the inhabitants of Edessa. Edessa was a major capital city in ancient times, before becoming a powerhouse of Christianity during its infancy. Armenian tradition recounts that the King of Edessa and Armenia, Abgar V, wanted to welcome Christ to his Kingdom and issued an invitation. It was not Christ who came to Edessa but one of his apostles Thaddeus (Jude). Edessa was renamed Urfa and remained the capital of the principality. This city has been known as Şanlıurfa since 1984 (in Turkey).

[2]In “Arménie, un atlas historique”, p.22 and map p.23. Publisher Sources d’Arménie, 2017.

[3]Source: Armenian Embassy in Iraq

[4]In « L’extermination des déportés arméniens ottomans dans les camps de concentration de Syrie-Mésopotamie ». Special edition of the review, Histoire Arménienne Contemporaine, Tome II, 1998. Raymond H.Kevorkian. p.15

[5]The website of the Armenian Embassy in Iraq reads as follows:“In 1914, there were 300 Armenian Catholics in Iraq. After the First World War and up until 2003, the community reached a total of 3,000 members. Nowadays, there are 200 – 250 Armenian Catholic families in Iraq. The Armenian Catholics have two churches: Our Lady of Flowers built in 1844, and the Sacred Heart of Christ built in 1937. In 1997, the main Armenian Catholic church was restored and is considered to be the largest church in Baghdad. The archbishop Emmanuel Dabaghian is the Primate of the Armenian Catholics in Iraq.”

Who was Sourp Sarkis (Saint Sarkis)?

The Armenian tradition says that Sarkis, a Greek from Cappadocia, was a centurion under Emperor Constantine who converted to Christianity and helped spread this new religion throughout the Roman Empire. To this end, Sarkis oversaw campaigns to destroy “pagan” temples and build churches. When Constantine died he was succeeded by Julian II, known as Julian the Apostate, who persecuted the Christians. Warned in a dream that he was in danger, Sarkis and his son Mardiros sought refuge in Armenia. Sarkis turned to the Persian Sassnid Emperor Shapur II and entered into his service to defend the Christian kingdom against the Roman armies, which he fought with valour. However, for proclaiming his Christian faith and refusing to worship the Zorastrian idols, Sarkis’ son Mardiros was put to death in 363 before Sarkis met with the same fate.

After his martyrdom, his followers recovered his bodies and took it out of Persia. His remains were recovered by Mesrop Machtots, creator of the Armenian alphabet, who took them to Ouchi, in Armenia where a chapel, then a monastery Sourp Sarkis were built.

Celebrated for his bravery and faith, Sarkis is represented riding a horse with his son Mardiros. They were both made saints by the Armenian Apostolic Church.

The feast day of Saint Sarkis and Mardiros is held on a moveable date between 11 January and 15 February. Numerous Armenian churches throughout the world were built under the patronage of Sourp Sarkis.

History of the village of Havresk and the Sourp Sarkis church

The history of the village of Havresk is directly linked to the genocide of the Armenians in 1915 – 1917. Large numbers of survivors in the Bakouba camp were re-settled close to the Iraqi border in the area around Zakho. Eleven Armenian villages like this were created in the 1920s and 1930s, Havresk, the largest of these, was built in 1927-1928. Five hundred families followed Levon Pacha Shaghoyan, an Armenian general who took part in Van’s resistance against the Turks, to Havresk. Levon Pacha Shaghoyan turned Havresk into a dynamic farming village.

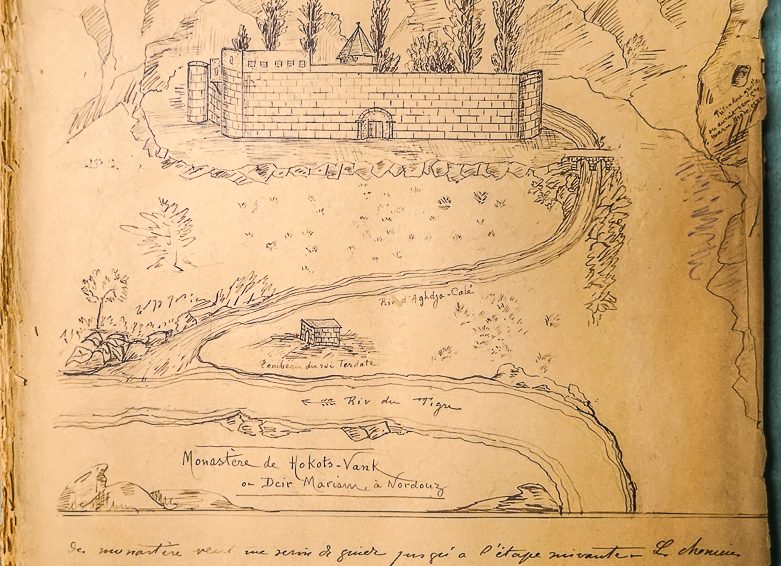

In 1928, the first Sourp Sarkis church was built from rough-hewn stones and earth.

In the period from 1944 to 1947 the wheat crops were blighted and the harvests diminished. Many families left the villages and headed to Basra to work for the oil industry. Havresk nonetheless continued to attract new arrivals, as in 1958 a large school was built for all the children in the region.

In 1975, after the Kurdish rebels led by Mustafa Barzani were defeated, Saddam Hussein decided to Arabise the entire region. He had Havresk evacuated and destroyed, as well as all the other villages in this sector. Forced to leave, the Armenians from Havresk settled in Mosul and Baghdad.

Following the fall of Saddam Hussein in 2003, the Armenian families from Havresk chose to return home in 2006, one year after the region officially came under the autonomous rule of Iraqi Kurdistan. The Kurdish government funded the initial construction of twenty houses in Havresk, supported by Sarkis Aghajan, a Christian benefactor and former Minister of the Economy and Finance. In the first year the living conditions were very difficult with no running water or electricity, but the reconstruction of the village continued with a new school, a community centre and by 2018, 115 houses which became homes not only for Armenian families but also, temporarily, for 85 families displaced from Qaraqosh and Bartella. Thanks to the efforts of its mayor, Mourard Vartanian, the village of Havresk has become a dynamic and attractive village. The inhabitants even continue to use the Armenian language and alphabet, thanks to an educational model put into place in 1958 and updated in 2006.

The new Sourp Sarkis church was built in 2010 with financial support from the German churches and the CAPNI (Christian Aid Program Northern Iraq).

Description of the Armenian Apostolic Church Sourp Sarkis in Havresk

The Armenian Apostolic Church Sourp Sarkis stands on a vast esplanade at the summit of the village, next to the ruins of the school built in 1958. The reinforced concrete building is painted inside and out. The roofs of the bell tower and drum are the only features characteristic of sacred Armenian architecture.

The entrance to the building, to the west, is preceded with a bell tower porch with rotunda and octagonal drum dome, mounted with a metallic Armenian cross.

Two other side doors on the south facade allow access to the nave and sacristy.

The church is formed of a flat, terrace roof hall, lit with abundant natural light thanks to the numerous windows in the north and south facades and the cupola.

A wooden choir screen separates the nave from the sanctuary. This is composed of two parts. The lower part can be accessed by worshippers during the Eucharistic communion. The upper part, the bem is reserved for priests and deacons. This is a tribune on which stands the high altar with steps, covered in marble slabs and decorated with an icon of the Virgin and child. Behind the high altar is a narrow ambulatory, which runs along the apse wall. Either side of the altar are the baptistery, to the left, and sacristy, to the right.

An octagonal cupola with drum and windows, with a pyramid roof stands above the high altar.

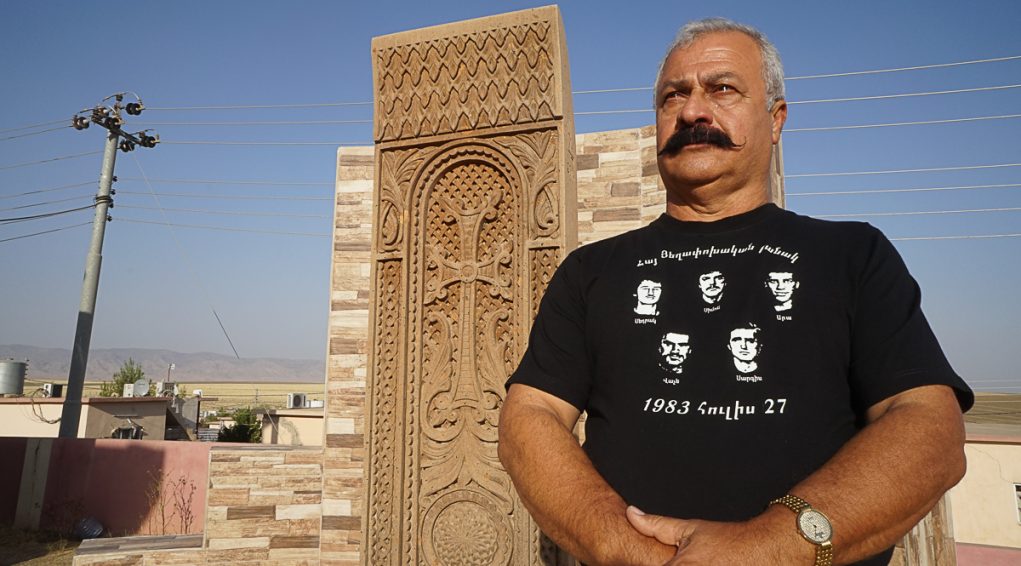

On the esplanade next to the church is a large khatckar (finely sculpted Armenian stone cross) erected in 2015, to commemorate the centenary of the Armenian genocide.

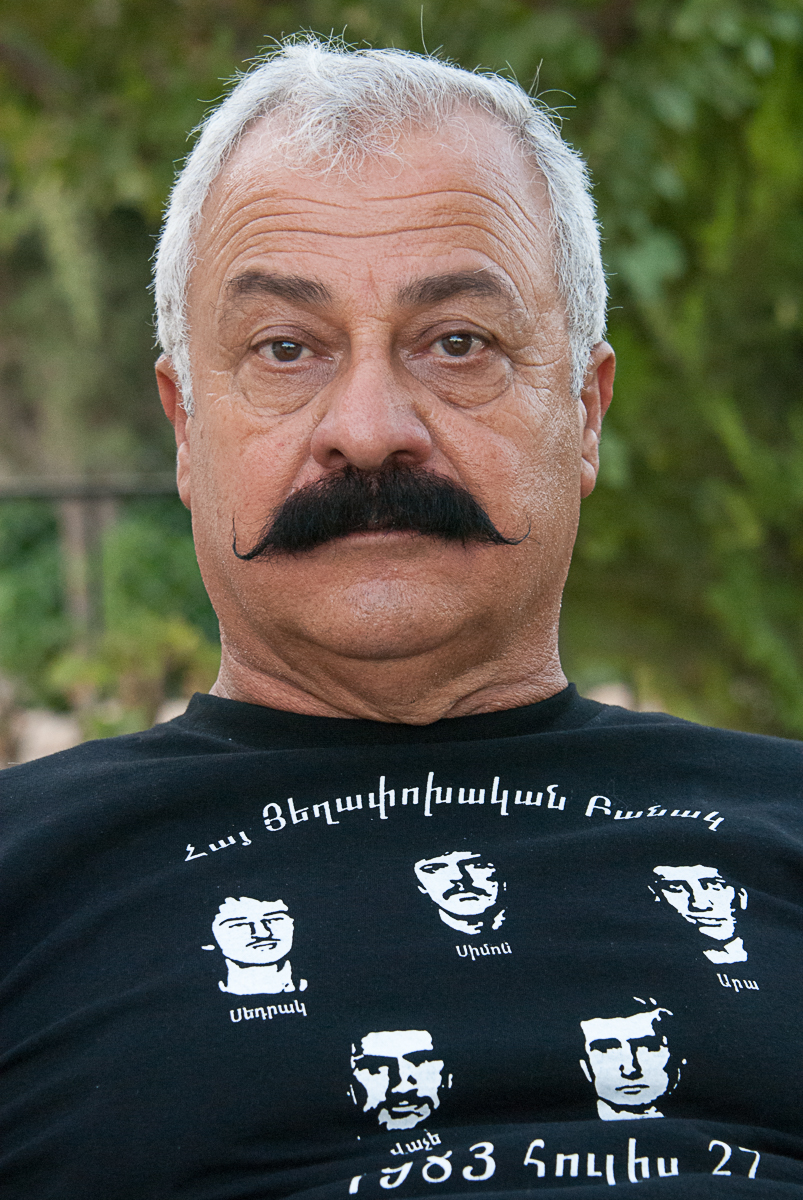

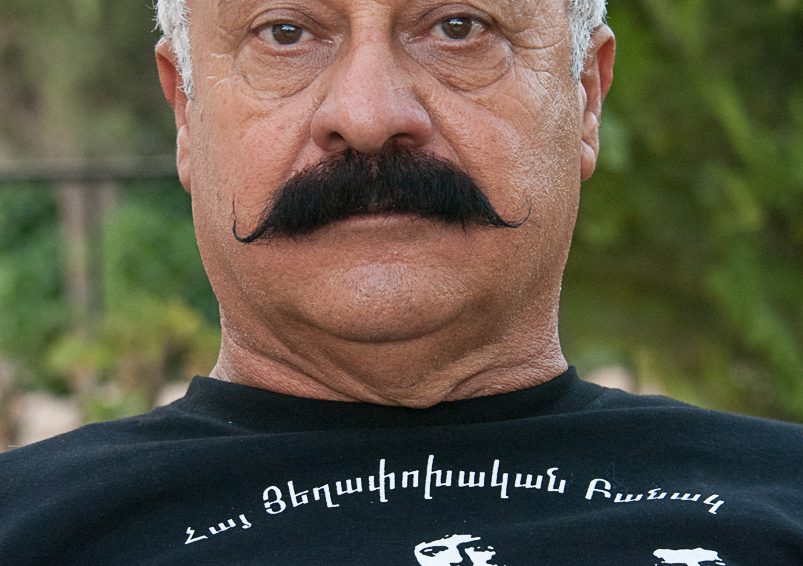

Testimony of Mourad Vartanian, mayor of Havresk

Information collected by Mesopotamia on 27 August 2017

The mayor of the village of Havresk, Mourad Vartanian, is the worthy heir to his distant counterpart Levon Pacha Shaghoyan. He fosters his ancestors’ spirit of resistance in the village. When ISIS invaded the Nineveh plain, Mourad Vartanian prepared and organised Havresk’s resistance with a group of Armenian fighters trained in commando operations. The commando took action in several conflict zones, specifically in Tell Escoff. However, the aims of Mourad Vartanian and his companions were altruistic: “Our fight is for peace. We give our lives for our churches and our people. We need to be brave and unafraid. We have faith in Jesus Christ. We believe in eternal life. We are not alone. God has a special plan. We have to stay.” Mourad Vartanian also advocates for the creation of an autonomous zone for Iraqi Christians in the Nineveh plain.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute