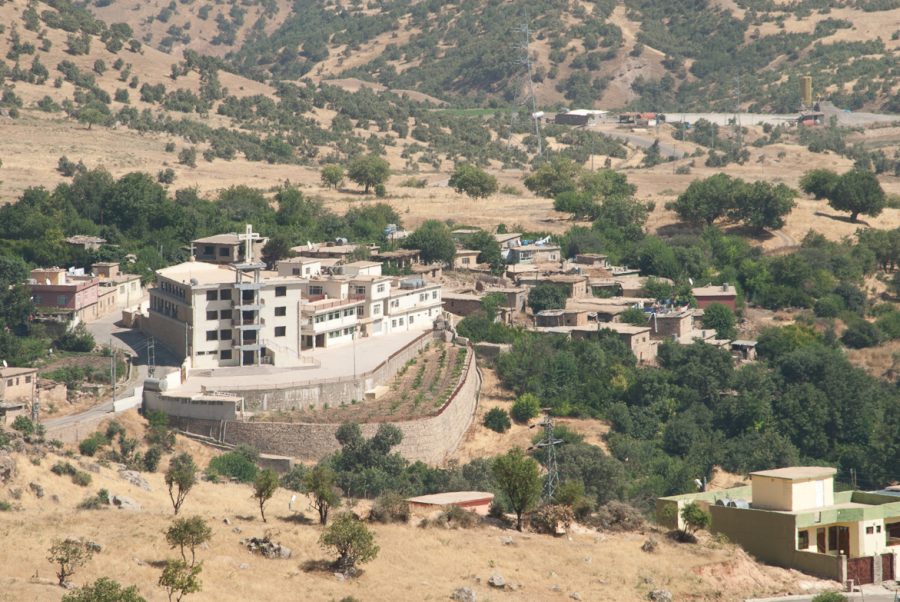

Mar Odisho Monastery in Dere

Mar Odisho Monastery in Dere lies 37°05’53.8″N., 43°31’15.3″E. and 1186 metres high. The hermitage just above the monastery lies 37°05’53.5″N., 43°31’17.8″E. and 1207 metres high.

There are not many precise and reliable sources about the original history of the primitive Mar Odisho monastery in Dere. It may have been built in the 4th century.

The building which followed in the 20th century has been destroyed in 1963 and rebuilt in 1985 and again totally ruined under Saddam Hussein in 1987.

The monastery’s reconstruction in 1995 and the lasting settlement of an Assyrian community of the Church of the East are absolutely outstanding.

Location

Mar Odisho Monastery in Dere lies 37°05’53.8″N 43°31’15.3″E and 1186 metres high. It is a high place of pilgrimage in the Church of the East. Its situation itself in the village of Dere reveals its position. Dere comes indeed from the word Dēr which in Syriac language means monastery (which is also said deir in Arabic and in Turkish). The village’s toponymy suggests indeed the former presence of an important place of worship, in that case Mar Odisho monastery.

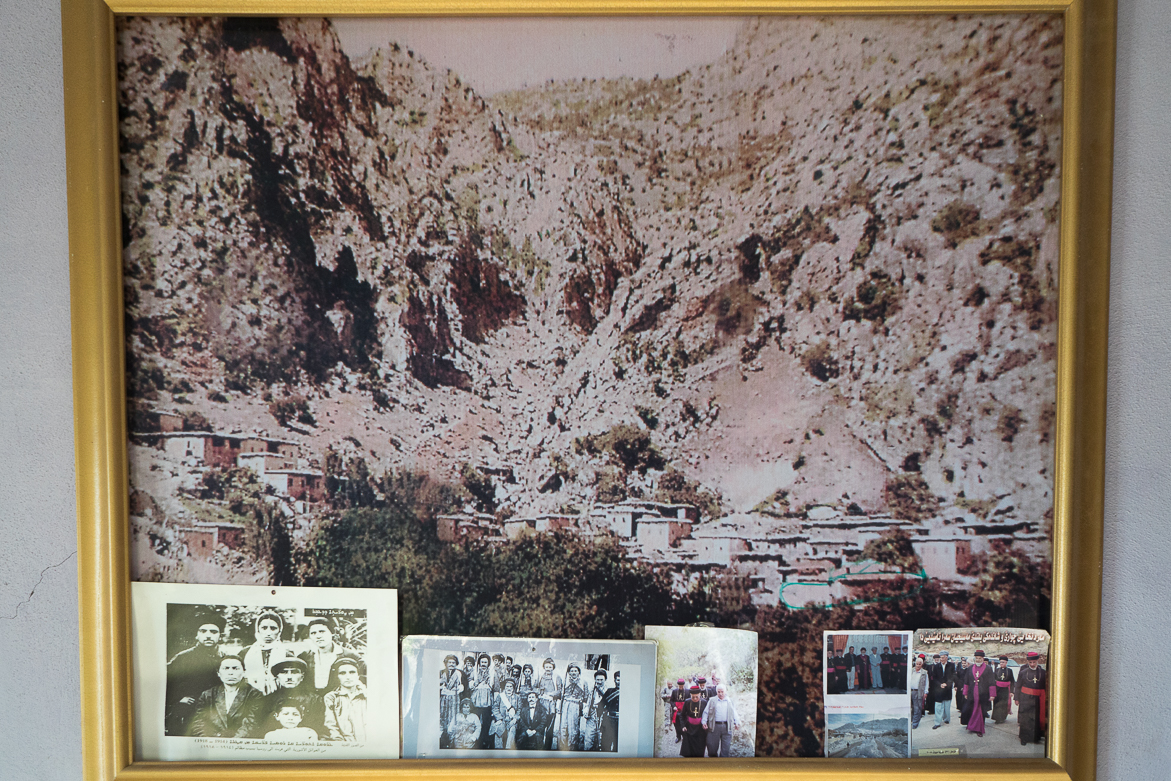

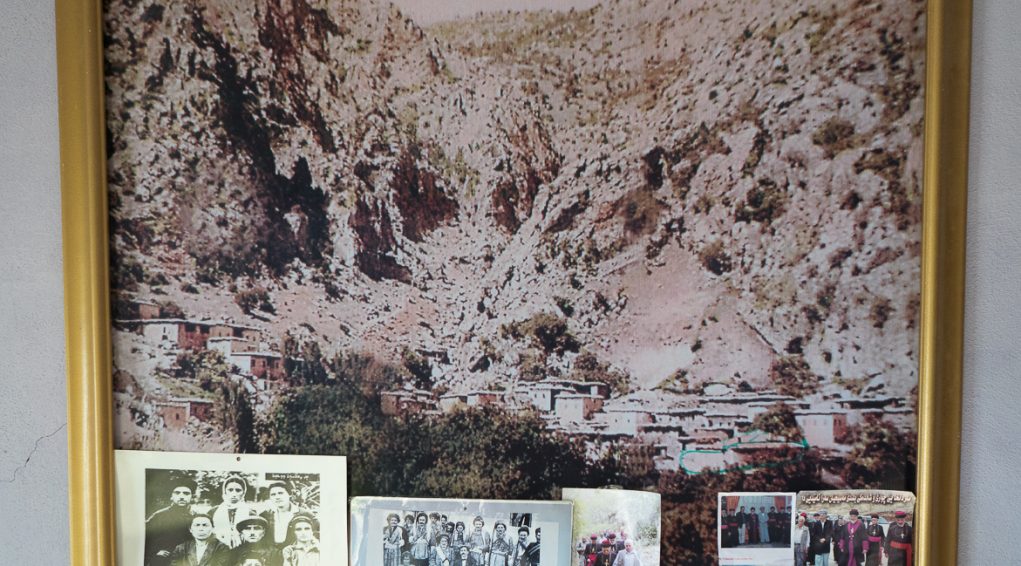

Mar Odisho Monastery is situated 4 km from Amadiya. To get there, you need to take a passable track that turns around on the side of the mountain, and runs along the cliffs, 3 km after getting through the Sulav gorge.

Mar Odisho monastery is set up in a wooded place, and withdrawn from the mountains overlooking the little village of Dere. It used to be only accessible to walkers or horse riders. The track has been widened and is now suitable for cars.

Fragments of Christian history

According to the tradition, the origin of the Church of the East would go back to the apostles and evangelizing preachers like Thomas, Addai (some assert that Addai is also the disciple Thaddeus, also known as Jude) and Mari. The new religion would have been preached especially addressed to local Jewish communities. Some saint preachers like Zeya and Sawa have also been appealed to from the 2nd century on.

Dere turned to Christianity just like all the other villages in the region of Amadiya. This Christianity was born from this apostolic tradition, which spread around Mesopotamia during the three first centuries, but it is really from the 4th century on and with the large number of martyrs persecuted by the Persian king Shapur II, that the Assyrian Church of the East really stepped into local history.

From the very long Christian history, let us notice that these mountains, very difficult to access to in old days, were both at the same time a place of flourishing and protection for the Church of the East.

At the end of the 19th century, under the Ottoman administration of the red Sultan Abdul Hamid II and up to the fall of the Empire in 1918, the sanjak[1] of Hakkari, to which Dere depended, had been integrated to the eastern vilayet[2] of Van, in order to have a better control upon Dere. It is important to mention that in the sanjak of Hakkari, in Qudshanis (also known as Konak), was the patriarchal sit of the Church of the East until 1915. The Assyrians there were “highly concentrated and represented a third of the population[3] ». Its eleven kazas[4], including these of Amadyia were for the most part “inhabited by Assyrians[5]”. The new administrative organization aimed at controlling the Christian Assyrian communities, which were quite autonomous in this withdrawn part of the Ottoman Empire, and this process has been completed with the 1915 genocide, committed by the Young Turks.

The rest of the 20th century was not much happier for the Assyrian-Chaldeans from those mountains. The different wars, so typical of the local and regional history from 1961, have had terrible consequences on the Christian cultural and architectural heritage.

[1] Territorial administrative division of the Ottoman Empire.

[2] Ottoman province, equivalent to a council.

[3] In Oubliés de tous. Les Assyro-chaldéens du Caucase, Joseph and Claire Yacoub, Les éditions du Cerf, 2015, p.26

[4] Another ottoman administrative division. A kaza is equivalent to a district

[5] id. note 3.

Fragments of a hagiography

The tradition relates that Mar Odisho lived in the 4th century, in a cave in the Bet Brach mountain range (near Shaqlawa and Arbil). He is also said to have stayed in Van (south east of modern-days Turkey). Wherever he used to live, he was imprisoned by the governor in Shaqlawa, the future Mar Qardagh. Converted to Christianity and baptized by Mar Odisho himself, Mar Qardagh was martyrized in Arbil for having refused to abandon his faith and turn back to paganism.

Great preacher of the Church of the East, Mar Odisho did not die as a martyr but gave his name to a large number of churches throughout Mesopotamia.

Odisho also means “servant of God” in Aramaic. This explains why so many Christian places bear his name in Mesopotamia.

The little history of an invaluable monastery

There are not many precise and reliable sources about original history of the primitive Mar Odisho monastery in Dere. It may have been built in the 4th century.

The building which followed in the 20th century has been destroyed in 1963 and rebuilt in 1985 and again totally ruined under Saddam Hussein in 1987. In such a historical and political context, the monastery’s reconstruction in 1995 and the lasting settlement of an Assyrian community of the Church of the East is absolutely outstanding. At the dawn of the 21st century, the rebirth of Mar Odisho’s sanctuary represents an invaluable historical value. It is again for thousands of pilgrims and visitors a very high spiritual place of the Church of the East.

Description of the monastery

Mar Odisho Monastery in Dere consists in a compound with religious and conventual buildings, opened onto an inner courtyard and small sloping woods.

A gate and a surrounding wall close the monastery on its northern side. A small path runs along the wall and leads to a water spring, much visited by tourists and pilgrims.

Built in cut stones, the religious building consists of three single-nave adjoining chambers one after the other, topped with three distinct roofs in reinforced concrete, each of them being surmounted by Assyrian crosses.

Once you pass the narrow gallery which runs along the building on the south west, you get into the first chamber: the Mariamana hall[1]. This room sized 6 meters by 3 is extended by a 6m² alcove which hosts an altar.

The following chamber is strickly speaking the church itself, dedicated to Mar Odisho. With its simple one-nave structure, and equivalent in size to the hall, it has a roof in the shape of a rounded arch and edged with crenels and merlons to imitate the Assyrian-Babylonian architectural style. On top of it, stands an arch-shaped bell tower. Inside, and as it is common use in all Assyrian churches, the altar stands after a royal gate and is protected behind a sanctuary curtain.

The last adjoining chamber is the Mar Qardagh church. Its simple nave is a little longer than the preceeding Mar Odisho’s church’s and it has a terraced roof. The sobriety of its inner arrangement preserves here again what is essential.

The Holy of holies (reserved to clergy) is separated from the rest of the church by a semi-circular arched royal gate, with on both sides, the minor gates leading to the sanctuary.

The cliff, on the shelf of which the monastery is nested, is pierced with caves which have been used undoubtedly as hermitages in old days. The tradition relates that Mar Odisho lived in one of those caves. Situated just a few dozen metres north east from the monastery, this cave lies at 37°05’53.5″N 43°31’17.8″E and 1207 metres high. It is locked with a little metal door.

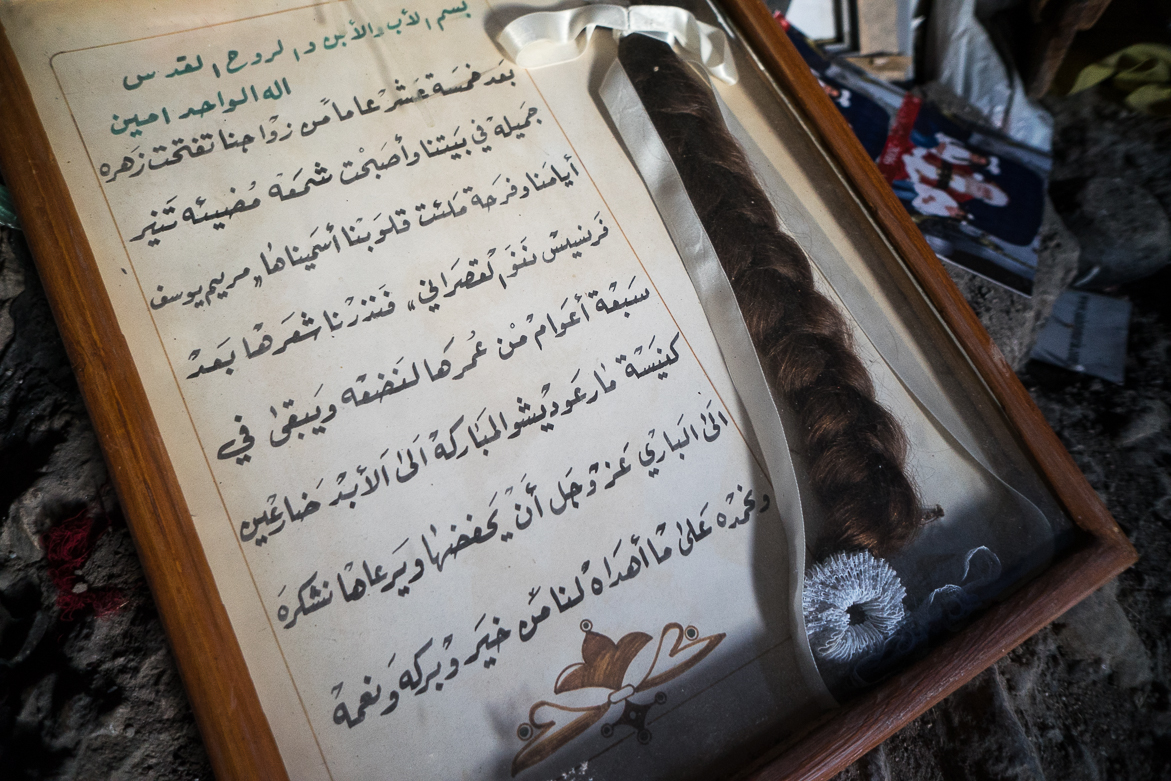

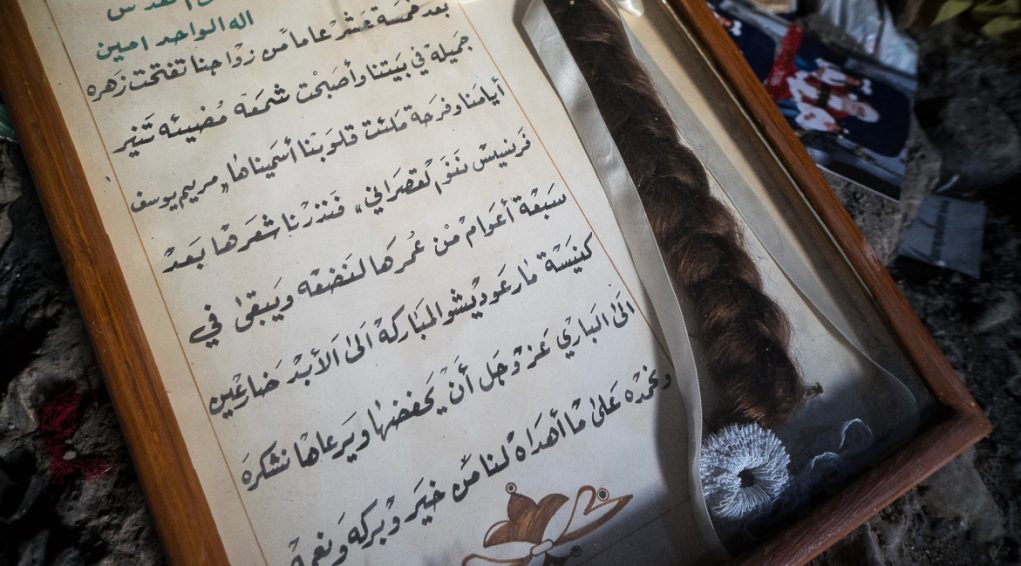

Mar Odisho’s hermitage is a high place of reverence where lots of pilgrims come to invoke the patron saint and ask for his intercession to grant all sorts of wishes. It is even more especially a “place of worship for the local women who cannot have a baby and come here to ask for fertility, and in particular those who want to expect a baby girl. If their prayers are granted, they cut a lock of their hair and offer it in the Dēr as a thank-you gift[2]”.

The pilgrims also offer in this cave all sorts of gifts as a testimony of their faith and gratitude.

[1] For the plan, see Les églises et monastères du « Kurdistan irakien » à la veille et au lendemain de l’islam, p. 242-244. PhD thesis of Narmen Ali Muhamad Amen. Université Saint-Quentin en Yvelines, May 2001.

[2] Id., p.244

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute