The Syriac-Catholic Al-Bichara Church in East Mosul

The Syriac-Catholic Al-Bichara church is located in East Mosul (east/left bank of the Tigris), in the Hay Al-Mohandisine district (the district of the engineers), at 36°21’46.8″N 43°08’26.7″E and 220 metres altitude.

The Al-Bichara church in East Mosul was created in 1970 to support the urban development of the city of Mosul and the movement of Christian families from the right bank (west) to the left bank (east). After the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003, the ensuing country-wide chaos severely impacted the Christian community which suffered persecution, kidnappings and murders. At this point, thousands of Mosulite Christians went into exile. At the same time the Al-Bichara church became a sanctuary for the families who remained in Mosul. After ISIS invaded Mosul on 10th June 2014, the last remaining Christians in Mosul fled to the Nineveh plain and Iraqi Kurdistan. Many of them gathered together in Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, specifically in the north sector of the city, in Ankawa. In the Ashti 2 displaced persons camp in Ankawa, a new Al-Bichara church was built (36°13’56″N 44°00’34″E and 434 metres altitude) in order to continue providing services and sacraments. For three years, this church became the focus on community life.

When Mosul was liberated, huge efforts were deployed to rebuild a new form of fraternity and promote the revival of the local Christian community. In East Mosul, Father Emmanuel, archpriest of the Syriac-Catholic Al-Bichara church, mobilised a number of partners in France (Œuvre d’Orient, Fraternité en Irak, Fondation Saint-Irénée) and Iraq to rebuild his church, along with a presbytery and student halls of residence. The civic inauguration took place on 7th December 2019 and was attended by the highest local and regional authorities. Its consecration took place the following day on 8th December 2019.

Pic: Inauguration of the new religious and social complex, encompassing the new Al-Bichara church, the presbytery and the student residence. December 2019 © Ghareed Sabah Zakaria / HAMMURABI for MESOPOTAMIA

Location

The Syriac-Catholic Al-Bichara church is located in East Mosul (east bank of the Tigris), in the Hay Al-Mohandisine district (the district of the engineers), at 36°21’46.8″N 43°08’26.7″E and 220 metres altitude.

Origins of the Syriac-Catholic church

The Syriac tradition attributes the evangelization of Mesopotamia to the apostle Thomas and his disciples Addai and Mari, however, “it seems that the introduction of Christianity in fact goes back only to the beginning of the 2nd century and that it was conducted under the influence of Judaeo-Christian missionaries from Palestine.[1]” This Mesopotamian Christianity started organizing itself in Seleucia-Ctesiphon, on the banks of the Tigris River, 30 km south from Baghdad, where the tradition reports that Saint Thomas made a halt on his way towards India. It was there, on a hill of the Koghe district, that the first patriarchal church of the Church of Mesopotamia was built and its catholicate was then established. This Syriac-language-based primitive Christianity still nowadays form the shared foundation of the local Iraqi churches and of their communities, which perpetuate this Christianity’s heritage and handover.

This shared foundation gradually broke up into a plurality of churches from the Council of Nicea in the 4th century up until the 20th century for geopolitical, rather than christological reasons.

Indeed, the first ecumenical Council of Nicea in 325, convened by the Roman Emperor Constantine I, was held without the Persian bishops, except from Jacob of Nisibis, as “it was out of the question to the other bishops, in times of never-ending or nearly never-ending war, to go and sit in an assembly held in an enemy country, convened – and even more presided – by the Roman Emperor.[2]” It should be said that from the Constantine’s conversion to Christianity on, the Sassanian Emperor Shapur II turned from tolerance to mistrust regarding the Persian Christians. This mistrust even turned to hostility: “The aim of the persecution was not to annihilate the Christians but to force them to abjure their faith, once their hierarchy had been wiped out.[3]”.

A century later, in 431, the Council of Ephesus sentenced the Patriarch of Constantinople Nestorius, who professed the two distinct natures of Christ (hypostasy): one divine, son of God, and one human, son of Mary. This Christological thesis was considered as heretic and Nestorius was removed from office. Due to geopolitical rivalries between the Roman Empire and the Persian Sassanian Empire, the Church of the East turned to Nestorianism from the second half of the 5th century on, and it spread throughout Mesopotamia, Persia and up to India.

Twenty years later, in 451, the Council of Chalcedon came up with a new Christological controversy. The Syriac, Egyptian, Ethiopian and Armenian Churches were blamed for professing a monophysite theory, i-e that within the person of Jesus Christ, the human nature was absorbed into the divine nature. Christ only has one divine nature.

In the 6th century, Saint Jacob Baradaeus, a Syriac monk, reorganised the Syriac church. After his episcopal ordination, he travelled to all the Syriac regions to ordain numerous bishops, priests and deacons. It was in his honour that the Syriac church was known as “Jacobite”. This (Orthodox) church split in the 18th century, in 1783, which gave birth to the Syriac-Catholic church in communion with Rome.

_______

[1] In “Vie et mort des chrétiens d’Orient. Des origines à nos jours”, Jean-Pierre Valogne, Fayard, March 1994, p.737

[2] In “Histoire de l’Église de l’Orient”, Raymond le Coz, Éditions du Cerf, September 1995, p. 31.

[3] In “Histoire de l’Église de l’Orient”, Raymond le Coz, Éditions du Cerf, September 1995, p. 33.

Fragments of Christian history in Mosul

Mosul[1] “remains a Christian metropolis”[2], as attested by its history, and its ancient and modern heritage, which persists despite recent catastrophic events.

Although the first archdiocese is attested to in 554[3], it is also important to take into account the Paleo-Christian apostolic tradition. “Three churches are proud to be founded on houses where apostles are said to have stayed. The Sham’ûn al-Safa’ church, [built during the Atabeg period in the 12th – 13th centuries] is said to be built where Saint Peter stayed during his visit to Babylonia and the Mar Theodoros church is connected to the visit of the apostle Bartholomew. As for the apostle Saint Thomas, the house where he was shown hospitality on his journey to India, became a church”[4]. The church in question is the Syriac-Orthodox church Mar Touma.

The first church attested to in Nineveh (modern-day East Mosul) dates back to the year 570. It is mentioned in the “Chronicle of Seert”. It is the Isha’ya church. This confirms a pre-existing Christian community. In the 7th century the Syriac-Orthodox Mar Touma church was also known of. From the 7th century onwards, the Mar Gabriel monastery was the seat of one of the Church of the East’s most important schools of theology and liturgy. The al-Tāhirā Chaldean church was built on the site of this monastery in the 18th century.[5]

Over the centuries, through successive councils and conflicts, a multitude of churches of different denominations, including the Armenian and Latin churches, were formed.

Of these various fragments of history, the Muslim conquest must be cited as one of the most important. Mosul fell in 641 and the Christian members of its population became dhimmis, with (limited) rights and (stringent) obligations based on their religious identity. This status remained in force up until the 19th century and was abolished in the Ottoman Empire in 1855. Despite this abolition, Christians (and Jews) still remain defined by their dhimmi status which governs denominational relations in public life and attitudes in almost all Muslim countries. It is still legally enforced (in Iran).

In the 7th and 13th centuries, at the height of the Seljuq period, the Atabeg dynasties imposed their rule throughout Iraqi Mesopotamia and made Mosul a centre of power. At this time, Syriac-Orthodox Christians persecuted in Tikrit fled to the Nineveh plain and Mosul, where they established their community and founded the Mar Ahûdêmmêh (Hûdéni) church. “At the end of the 20th century due to below-ground flooding throughout the neighbourhood, the Mar Hûdéni church located well below ground level was flooded and had to be abandoned. A new church was built right on top of the old one. Thankfully, the royal door in the Atabeg style, described by Father Fiey as a “jewel of 13th century Christian sculpture”, was transported to the new church and given pride of place.”[6]

Following on from the Atabeg, the Mongol Houlagou Khan, took Mosul but spared the city from destruction and from the massacres committed in Baghdad in 1258, thanks to the “cunning governor of the city, Lû’lû, of Armenian origin.”[7]The following century was nonetheless a tragic one. “Christian persecutions peaked under Tamerlan, whose armies ravaged the Middle East in the first years of the 14th century and exterminated the Christian populations. No other eastern Christian church underwent anything close to this type of eradication, the community in Iraq is well placed to claim the first prize in martyrdom.” [8]

In 1516, Mosul fell into the hands of the Ottoman Turks for the first time, but it was not until the following century that they established a dominant presence in Iraqi Mesopotamia that was to last for four centuries after the conquest of Baghdad in 1638 by the sultan Murad IV.

Mosul in the 16th century was a major centre of Christian influence. It was here that the schism of the Church of the East took place, with the election of Yohannan Sulaqa as the first patriarch of the Chaldean church Abbot of Rabban Hormizd Monastery in Alqosh, he took on the name Yohannan/John VIII and went to Rome to profess his Catholic faith. On 20th April 1553, Pope Julius III appointed him Patriarch of the Chaldean Catholic church “whose creation was thus officialised.”[9] After Diyarbakır (in the south-east of modern-day Turkey) and before Baghdad (in 1950), the seat of the Chaldean church was established in Mosul in 1830, with the election of Jean VIII Hormez as the metropolitan of Mosul.

In 1743, the Christians of Mosul played an active role in defending the city during the 42-day siege laid by the Persian Nâdir Shâh who had already looted and ransacked the plain of Nineveh. Victorious and grateful, the pasha of Mosul, Husayn Djalîlî “obtained a firman from Constantinople favourable to the churches of Mosul.”[10] In 1744, the two al-Tāhirā churches were built in Mosul, one for the Chaldeans, one for the Syriac-Catholics (the latter was restored and rebuilt). The churches damaged by bombs were also restored.

After the schism in the Syriac church (Orthodox Jacobite) in 1783 and the creation of the Syriac-Catholic church, there was a conflict between the Syriac-Orthodox and Syriac-Catholic churches regarding ownership and use of the church buildings. This conflict was resolved in Mosul by building two new churches, al-Tahira and Mar Touma, in 1862 and publishing an Ottoman firman (decree) in 1879 dividing the assets and ownership of churches and monasteries between the two denominations. The first Syriac-Catholic bishop in the diocese of Mosul was Quorls Bchara Bhnam Akhtal (1760-1828).

The 17th century marked the opening of the Latin missions in Iraqi Mesopotamia. The Capuchin Friars open their first house in Mosul in 1636. The Dominicans of the Province of Rome arrived in 1750, followed by those from the Province of France in 1859. Under their impulsion, the large Latin church Our Lady of the Hour, was built “in the Byzantine style, between 1866 and 1873.”[11] This is the church to which the empress Eugénie de Montijot, wife of Napoleon III, donated the famous clock which was placed in the first clock tower ever built in Iraq. For almost three centuries, members of the Dominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia, have been actors, experts and vital witnesses to the history of Christianity in Iraq.

A turning point came in 1915-1918 with the genocide of the Armenians, Assyrians and Chaldeans in the Ottoman Empire. Large numbers of survivors came to live in Iraqi Mesopotamia, specifically in Mosul where there were pre-existing Christian communities. During this period, in January 1916 over just two nights, 15,000 Armenian deportees living in Mosul and the surrounding area were exterminated, tied together in groups of ten and thrown into the Tigris river. Already, well before this carnage, on 10th June 1915, the German consul to Mosul, Holstein, telegraphed his Ambassador, reporting telling scenes: “614 Armenians (men, women and children) expulsed from Diarbekyr and transported to Mosul, were all killed en route, as they were transported by raft (on the Tigris). The kelek arrived empty yesterday. For a few days now the river has been carrying corpses and human limbs (…)” [12]

_______

[1] This chapter is largely based on the work of Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux [1] o.p. who lived in Iraq for 14 years from 1969 to 1983 as part of the Dominican mission for Mesopotamia, Kurdistan and Armenia, based in Mosul. See, two books by Brother Jean-Marie Mérigoux, in particular: « Va à Ninive ! Un dialogue avec l’Irak », Éditions du Cerf, October 2000; and « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Éditions La Thune, Marseille, July 2015.

[2] In “Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien”, Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Éditions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p.88

[3] In Assyrie chrétienne, vol.II, Jean-Maurice Fiey. Beirut, 1965. P. 115-116. See also “Mossoul chrétienne” by Jean-Maurice Fiey.

[4] In « Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien », Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 89

[5] In “Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien”, Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 92-93

[6] In “Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien”, Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 94

[7] In “Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien”, Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 95

[8] In “Vie et mort des chrétiens d’Orient”, Jean-Pierre Valogne, published by Fayard, 1994, p.740

[9] In “Histoire de l’Église de l’Orient”, Raymond le Coz, Éditions du Cerf, 1995, p. 328

[10] In “Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien”, Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 97

[11] In “Entretien sur l’Orient chrétien”, Jean-Marie Mérigoux. Editions La Thune, Marseille, 2015, p. 102

[12] In “L’extermination des déportés arméniens ottomans dans les camps de concentration de Syrie-Mésopotamie.” Special edition of Revue d’Histoire Arménienne Contemporaine, Tome II, 1998. Raymond H.Kevorkian. p.15

Contemporary history of Mosul

In the year 2000, “50,000 Christians were living in Mosul.”[1] For the 11-year period, between the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime on 9th April 2003 and the ISIS invasion on 10th June 2014, the inhabitants of Mosul were subjected to the terror inflicted by Islamic and organised crime gangs run by Al-Qaïda, “who perpetrated kidnappings, murder and extorsion against the Christians in the city.”[2] Throughout this period crimes against Christians, both secular and ordained members of the church, increased exponentially and forced them into exile.

On 1st August 2004, simultaneous attacks against five churches in Mosul and Baghdad triggered the mass exodus of the Christians of Mosul to protected areas in the Nineveh plain, Iraqi Kurdistan and overseas. The next few years in Mosul were truly harrowing.

On 6th January 2008, Epiphany, and 9th January, criminal attacks targeted several Christian buildings in Mosul and Kirkuk.

It was in this climate of terror that Monsignor Paulos Faraj Rahho, the Chaldean archbishop of Mosul was kidnapped. “On 13th February 2008, as he welcomed a delegation from Pax Christi, in the church in Karemles, right next to Mosul, the prelate revealed that he had been threatened by a terrorist group several days previously, “Your life or five hundred thousand dollars,” the terrorists told him. “My life is not worth that!” he replied. One month later, on 13th March, Monsignor Rahho was found dead at the entrance to the city.”[3]

When ISIS took control of Mosul in 2014, the proto-state that was established completed and amplified the catastrophe. The new order and the caliphate would bring an end to the existing anarchy! Tyranny was elevated to a political system, led by man self-proclaimed Caliph on 29th June 2014, Abou Bakr al-Baghdadi, who appeared in public on 4th July 2014, preaching at the al-Nouri mosque. When ISIS took control of Mosul, it implemented its totalitarian politics against the non-Sunni population: Shia Muslims, Shabak, Christians and Yazidis. The homes of the 5,000 Christians who did not flee Mosul when ISIS entered the city, were marked with the Nazrani symbol (Nazarene i.e. disciples of Jesus). After this stigmatisation, they were issued an ultimatum on 17th July: convert to Islam (Sunni-Salafist Islam), pay the djizia (tax on the dhimmi), leave or perish. The outcome was inevitable. They all fled the city towards the Nineveh plain and Iraqi Kurdistan and lost absolutely everything on the way. Their abandoned monuments and heritage were pillaged, vandalised and profaned.

After ISIS was defeated militarily in the Nineveh plain in the autumn of 2016, the displaced Christians progressively returned to their villages as of April 2017. They returned to their homes and churches which had often been ransacked and burned down. Mosul was only truly liberated 10 months later during the summer of 2017, by the international coalition which not only crushed ISIS with its firepower but also pulverised a number of major Assyrian, Jewish, Christian and Muslim buildings in Mosul.

Unlike the displaced Christians from the Nineveh plain, those who had left Mosul did not return home. The extent of the destruction of the heritage monuments in the old city, not only due to ISIS but also the persecution inflicted on the Christian community since 2003, the impunity of criminals still acting freely, the collective humiliation they were subjected to and the betrayal of trust by their Muslim neighbours made any mass return unlikely, although dozens of brave families did return to the city.

When Mosul was liberated, huge efforts were made to rebuild a new form of fraternity and promote the revival of the local Christian community. Several French personalities and organisations played an active role in supporting local churches. These include: Œuvre d’Orient, Fraternité en Irak, Fondation Saint-Irénée.

Responding to the call from the Chaldean Patriarch, Louis Raphaël I Sako, and in collaboration with the city authorities, Œuvre d’Orient supported the restoration of the St Paul Chaldean church in East Mosul. Father Thabet, the Chaldean archpriest of Karamles and Mosul, played an important role in this revival, mobilising young Christian and Muslim volunteers who cleaned the church together. A Christmas Eve service was held on 24th December 2017 in the morning led by the Chaldean Patriarch, with representatives from sister churches, the Syriac-Catholic archbishop Petros Mouché and Syriac-Orthodox archbishop Nicodemus Daoud and attendees from the Mosulite political, civil and military authorities “for a moment of faith, courage, forgiveness and fraternity between churches.”[4] The Saint Paul church became the first Christian parish in Mosul to be renovated. On 24th January 2019, the new Chaldean archbishop of Mosul, Monsignor Najeeb Michaeel, appointed on 22nd December 2018, presided over a service in this fully-restored building, attended by a large crowd. On 21st April 2019, dozens of people came to celebrate Easter in the Saint Paul church with their archbishop.

In the old city of Mosul, where there is the highest concentration of centuries old Christian heritage, the Syriac-Catholic Mar Touma church was partially renovated and put back into service, once again with help from Œuvre d’Orient. The altars in the church were restored by the architects Guillaume and Laure de Beaurepaire. Since 2018, the feast day of Saint Thomas, the apostle of Mesopotamia, is celebrated every 3rd of July bringing together numerous worshippers and clergy.

Finally, in East Mosul, Father Emmanuel, archpriest of the Syriac-Catholic Al-Bichara church, mobilised a number of partners in France (Œuvre d’Orient, Fraternité en Irak, Fondation Saint-Irénée) and Iraq to rebuild his church, along with a presbytery and student halls of residence. The civic inauguration took place on 7th December 2019 and was attended by the highest local and regional authorities. Its consecration took place the following day on 8th December 2019.

Ultimately, in Mosul, any possible revival and return of the displaced populations “requires at the very least the rehabilitation and regeneration of the city’s heritage, along with an improvement in the security situation and the restoration of trust.”[5]

_______

[1] Source Father Emmanuel Kallo, Syriac-Catholic archpriest of three Syriac-Catholic churches in Mosul including the Al-Bichara church in East Mosul. Interviewed by Mesopotamia on 15th April 2017. Christian Lochon, Honorary Director of Studies at the CHEAM has a different estimation which evokes 25,000 Christians in Mosul in 2003 before the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime, in the Œuvre d’Orient Review, “Qaraqoche ou la disparition des chrétiens de la plaine de Ninive”, 2015, p.136-137.

[2] In Revue de l’Œuvre d’Orient, “Qaraqoche ou la disparition des chrétiens de la plaine de Ninive”, Christian Lochon, Honorary Director of Studies at the CHEAM, 2015, p.136-137

[3] In « Chrétiens d’Orient : ombres et lumières », by Pascal Maguesyan, Éditions Thaddée, September 2013, latest edition 2014, p. 260 260

[4] https://oeuvre-orient.fr/actualites/loeuvre-dorient-va-reconstruire-leglise-saint-paul-de-mossoul-irak/

[5] in “Le Bulletin de l’ Œuvre d’Orient”, n°798, January-March 2020, Pascal Maguesyan

History of the Al-Bichara church in East Mosul, prior to ISIS

The Al-Bichara church in East Mosul was created in 1970 to support the urban development of the city of Mosul and the movement of Christian families from the right bank (west) to the left bank (east).

Although the mother Syriac-Catholic churches in Mosul – the Al-Tahira cathedral and Mar Touma church – remained the focus of worship on Sundays and feast days up until the start of the 1990s, the Syriac-Catholic diocese of Mosul decided to build the Al-Bichara church to meet the needs of the families living in the new eastern districts of Mosul [Hay Al-Mohandisine – the district of engineers -, Al-Sukar, Al-Masarif, Al-Majmouaa al-thaqafiya, Al-Darqzliya, Al-Zhore, (…)] to celebrate services and sacraments including baptisms, weddings and funerals, (…).

The Al-Bichara church enjoys a strategic location in the Hay Al-Mohandisine district. The surrounding roads are wide and easy to access by car, unlike the historic churches (the Al-Tahira cathedral and Mar Touma church) which are located in ancient, narrow alleyways.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Al-Bichara was only used by Syriac-Catholic worshippers for Sunday mass, the main feast days and sacraments. At the start of the 1990s the church began to develop its pastoral role including catechism classes over the summer. At the start of the 2000s, the church expanded its role in response to the political changes implemented following the fall of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003. The ensuing chaos throughout the country had a severe impact on Christians who suffered persecution, kidnappings and murders, as well as being socially, professional and politically marginalised. At this point, thousands of Mosulite Christians went into exile. At the same time the Al-Bichara church became a sanctuary for the families who remained in Mosul. The church became a place of hope, peaceful and secure, where Christians could come together not only for services but also to partake in cultural and social activities. These activities included a forum for women involved in the church and society, gatherings for young people and meetings for teenagers, activities for the elderly and families, a creche for children aged 1 – 6 years and a nursery school.

The Al-Bichara church, from Mosul East to the Ashti 2 camp in Ankawa.

After ISIS invaded Mosul on 10th June 2014, the last remaining Christians in Mosul fled to the Nineveh plain and Iraqi Kurdistan. Many of them gathered together in Erbil, the capital of Iraqi Kurdistan, specifically in the north sector of the city, in Ankawa. They took refuge in makeshift accommodation, tents, caravans, buildings and schools.

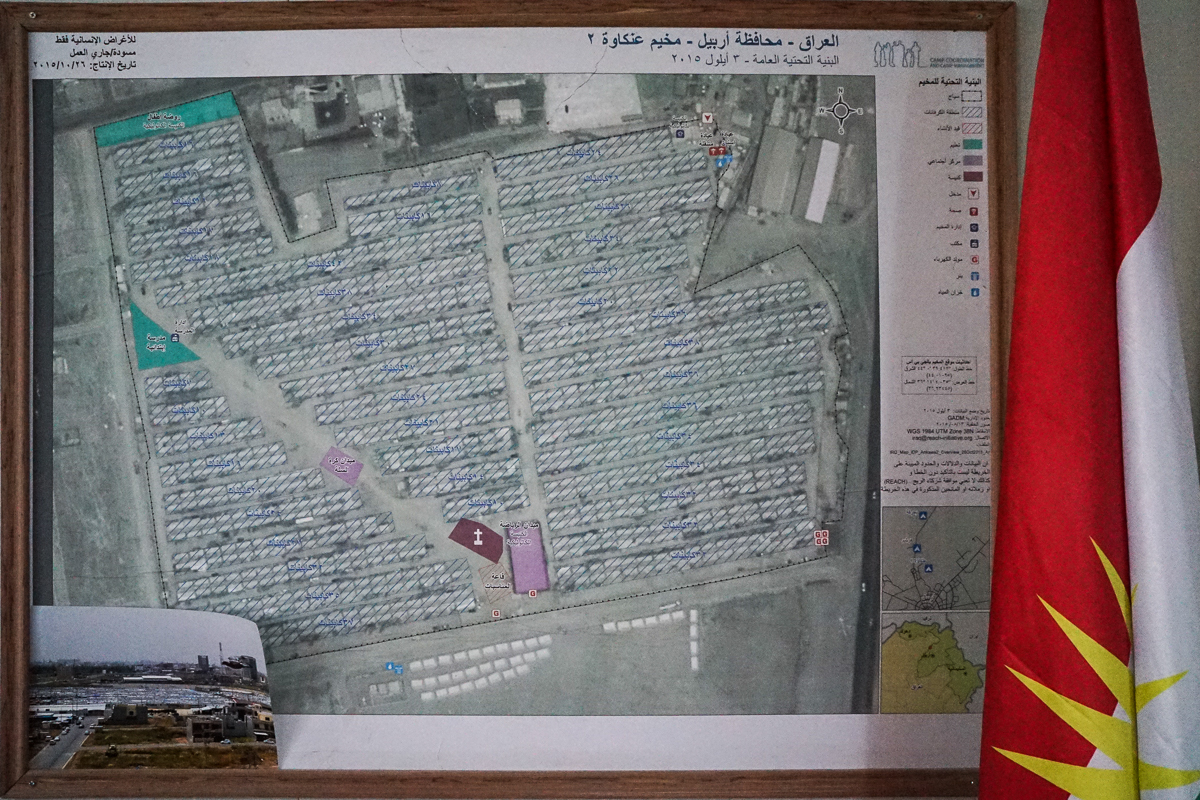

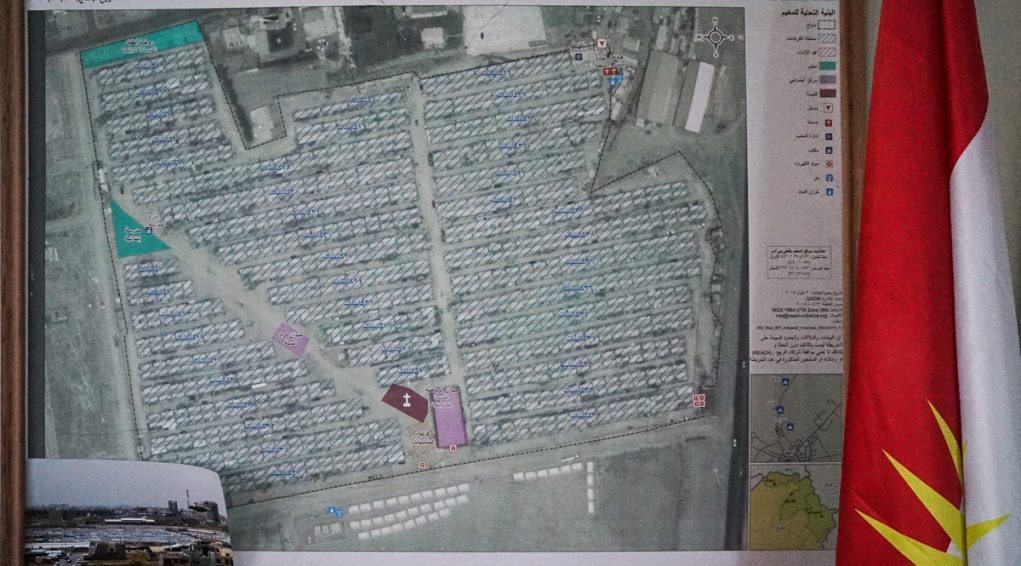

The Ashti 2 displaced persons camp in Ankawa, home to 1,250 families (5,000 people) displaced from the Nineveh plain and Mosul, was run by Father Emmanuel Kallo, archpriest of the Syriac-Catholic Al-Bichara church in East Mosul, seconded by Ibrahim Lallo, a French-speaking deacon from Bartella. The living conditions were harsh, in particular during the intense heat of the summer months from June to September.

It was in this camp that a new Al-Bichara church was built (36°13’56″N 44°00’34″E and 434 metres altitude) in order to ensure a continuity of spiritual life and worship. This was achieved with the financial support of the French charity Fraternité en Irak. The construction of the building, which resembles a large hangar, was overseen by a civil engineer, Munthir Rufail, a Syriac-Catholic displaced from Bartella. It uses innovative, high-quality, ready-to-assemble composite panels produced by the French firm Logelis.

In this way, for three years, the Al-Bichara church in the Ashti 2 camp in Ankawa became a community centre, helping the refugees and organising pastoral and cultural activities for children and adults. The last service in the Al-Bichara church in the Ashti 2 camp in Ankawa, presided over by Father Emmanuel Kallo, was held on Sunday 2nd June 2018. On 10th June 2018, four years to the day that Mosul had to be abandoned, the church was moved to East Mosul.

Life at the Al-Bichara church in the Ashti 2 camp in Ankawa: Testimony of Pauline and Jean Bouchayer.

A number of remarkable people such as Pauline and Jean Bouchayer gave two years of their life in service to the displaced persons from the Nineveh plain and Mosul, comforting them and praying for them. Sent to Iraq by the archbishop of Lyon, Cardinal Philippe Barbarin, mandated by Fidesco (a Catholic international solidarity organisation), in collaboration with the Fondation Saint-Irénée of the Lyon diocese, they were specifically tasked with delivering French lessons at the Saint-Irénée school in Ankawa.

In the Al-Bichara church in the Ashti 2 camp in Ankawa, their mission was also one of prayer. “The arrival of Carine Neveu, Sister of the Community of the Lamb, (…) was a genuine blessing for us (…). We set up a prayer school with her for the children in the Ashti camp every Friday morning. It was a wonderful time which gave us a glimpse of the faith of these children which caused us to question our own faith. In the last three weeks before Christmas we also set up a vigil for adoration of the Blessed Sacrament on the Thursday evening (in addition to the Tuesday organised by the Little Sisters of Jesus). We waited until Abouna Emmanuel, priest and camp director, had gotten to know all three of us, and trusted us, before we made this suggestion (…). Leading these prayer evenings in French and Arabic and having him join us was a wonderful gift. For Lent, he asked us to lead three vigils. We were systematically supported by the Little Sisters of Jesus for these prayer times. We took care not to take over from anyone, to be there either in a support role, or to make suggestions, whilst taking care not to do things in people’s place.” [1]

“Since the arrival of Carine, who we mentioned in our previous reports, we have set up a prayer school for the children in the Ashti 2 camp. Carine has a genuine gift and several years’ experience in prayer with children in difficult post-emergency settings. Unfortunately, Carine returned to France on 31st May. She was a huge support for us. Her humanitarian and missionary experience has helped us immensely. (…) Before she left Carine did training to pass on and disseminate the prayer school. Indeed, she considers that prayer can help young children to heal after experiencing traumatic situations. They have a much greater capacity than adults to abandon themselves to God, they have a much simpler relationship with the divine. This weekly hour-long prayer session helps children who have experienced extremely dangerous situations to gradually find some calm and connect with the essential. We are also convinced of this and will continue to lead the sessions without her. We will also continue with the adoration of the Blessed Sacrament with the Little Sisters of Jesus (sister of Charles de Foucauld) once a week in the camp church.”[2]

_______

[1] In Mission Report N°3. March 2017

[2] In Mission Report N°4. June 2017

The new Al-Bichara church in East Mosul

In order to encourage the inhabitants to return, it was important to rebuild the Al-Bichara church on its original site in the Hay Al-Mohandisine district of East Mosul. More than just the church, an entire complex was recreated. It includes a presbytery, a multi-denomination meeting place, a residence for Christian and Muslim students attending the Mosul universities. “This new space sends a message out to the whole of society. To the Christians, to help them overcome their suffering and continue to work for the salvation of humanity. To the Muslims as well, who can see this place as a living symbol of forgiveness and a rejection of any form of malevolence, to allow peace and security to return to this afflicted city. Because there is no life without peace, no peace without forgiveness, no forgiveness without love. Living together requires love, forgiveness and peace.”[1]

The new Al-Bichara church was rebuilt on top of the old church destroyed by ISIS. The new building was built using the composite Logelis panels dismantled and moved from the Ashti 2 camp in Ankawa, to the site in the Hay Al-Mohandisine district of East Mosul. Significant improvements were made to the building, in particular the addition of external breeze block insulation. It was important to make the church look like a permanent rather than a temporary building. The interior decoration was enhanced with netting on the ceiling, stained glass windows on the side walls and very dense lighting. A balustraded walkway borders the main facade of the church. The estate courtyard serves as an esplanade, around which other buildings have been built. Fraternité en Irak funded the construction of the new Al-Bichara church. Œuvre d’Orient funded the construction of the magnificent presbytery. The Fondation Saint-Irénée financed the student halls of residence. The civic inauguration which took place on 7th December 2019 contained a number of gestures of fraternity between Christians and Muslims, who were fully included in this inaugural ceremony. The consecration of the church on 8th December 2019, was attended by large crowds and the most senior members of all the Christian denominations in Iraq, as well as the French Cardinal Philippe Barbarin.

_______

[1] Father Emmanuel Kallo, the Syriac-Catholic archpriest of the Al-Bichara Church in East Mosul. Extract from his speech written for the study day “What future for the monumental heritage of the Christian and Yazidi communities in Iraq?” organised by Mesopotamia on 29th June 2019 at the Erbil International Hotel.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute