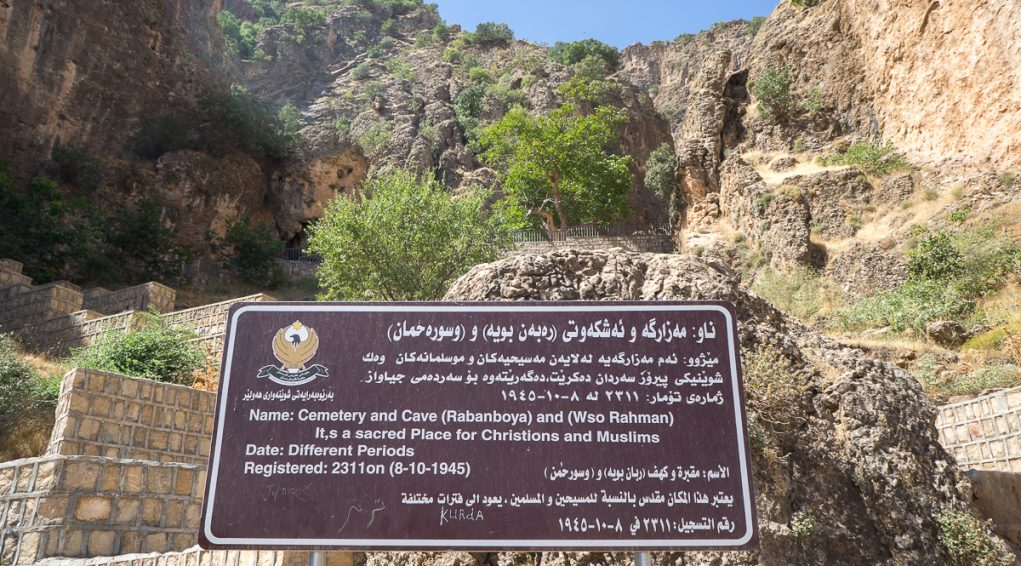

Shrine of Raban Boya in Shaqlawa

The shrine of Raban Boya in Shaqlawa lies at 36°23’29.1″N 44°19’41.9″E and sits 1070 metres high.

Overlooking the valley of Safeen Mountain, the shrine, which used to be a simple mountain hermitage at the beginning, is now a high place for pilgrimage, especially for women, both Christian and Muslim, who appeal to Saint Boya to grant their fertility wishes.

Nowadays, the path has been fixed up on the first half of the way so that pilgrims and visitors can make their way more easily, but when strolling on the second half on the path, one can still feel the truly basic and rudimentary way of life in the first times of Christianity in Shaqlawa and of Raban Boya’s hermit life.

Map of the shrine of Mar Raban Boya[1]

[1]Plan in « Les églises et monastères du “Kurdistan irakien“à la veille et au lendemain de l’islam ».PhD Thesis by Narmen Ali Muhamad Amen the University of Saint Quentin en Yvelines, under the direction of George Tate and co-directed by Jean-Michel Thierry. May 2001. P.211.

Location

The shrine of Raban Boya lies at 36°23’29.1″N 44°19’41.9″E and 1070 metres high, in the city of Shaqlawa, east of the Great Zab and 48 km northeast from Erbil. The shrine is literally nestled in the very heart of a steep and narrow gorge on Safeen Mountain, foothills of the Iraqi Kurdistan mountain range. The hermitage makes a sort of spur, overlooking the town of Shaqlawa and the valley. The shrine is also known as Rabban Beri, in particular for the Christian community of Shaqlawa[1]or even Rabban Berīor also, “as the Kurds call it in Shaqlawa, Šeih ŪsūRahman[2]”.

[1]According to Ninos Hanna, native from Shaqlawa and living in Ankawa, the name Rabban Boya seems to be used especially by the Christians from Ankawa.

[2]In « Les églises et monastères du “Kurdistan irakien“à la veille et au lendemain de l’islam ».PhD thesis by Narmen Ali Muhamad Amen at the University of Saint Quentin en Yvelines (France), directed by George Tate and co-directed by Jean-Michel Thierry. P.209. May 2001.

Fragments of Christian history

The local history of Shaqlawa is first of all the history of the whole region of Mesopotamia, which became kingdom of Adiabene, with Erbil (Arbeles) as capital-city, and where Judaism was strongly implanted. This region is supposed to have been evangelized directly by some apostles of the Christ, and in particular by Thaddeus (Addai) and Thomas who came along with their disciples. It is more than probable that the first Christian communities they started to develop emerged from local Jewish communities. As from the very first centuries, those communities endured persecutions, for instance from Persians or Assyrians. They were not necessarily regular nor continuous, but recurring and gruelling persecutions, always depending on the different sovereigns’ goodwill as much as on geopolitical tectonic shifts.

At the beginning, the shrine of Raban Boya was only but a hermitage, just as there are so many in these Kurdish mountains. It seems to have turned afterwards to adeir, that is to say a monastery. There are indeed evidences that “some monks used to live here and ran a little weaving industry, making clothes with goat’s hair[1].” There are no more monks living as hermits in the mountains today. The site is still maintained as a mausoleum and is known for hosting the revered relics of a few saint monks, such as those of Monk Boya.

Shaqlawa is a big Kurdish town of 25 000 people and part of the Erbil governorate. It still nowadays hosts a small Christian community, mainly composed of Chaldeans, counting around 150 families[2], and also many displaced Iraqi Christians. Just a few decades ago, there were still 500 Christian families living in Shaqlawa.

Fragments of a tradition

Raban Boya probably lived at the same time as Mar Audicho’ and Mar Qardakh, that is to say in the 4thcentury. Their fates are indeed linked to one another, as the venerable saint man is mentioned in Mar Qardāg’s hagiography. According to what the tradition mentions, Raban Boya lived nearly up to 68 years, and lived a life of prayer and asceticism in his hermitage in Shaqlawa.

One night, God ordered him in a dream to get up and go to visit Mar Audicho’ in his cave on the Bet Brach Mountain (not far from Shaqlawa and Erbil). Though he was already getting old, Raban Boya set off for the mountain and both his courage and ardour impressed Mar Audicho’. Once there, Raban Boya is said to have met with the future Mar Qardakh to reinforce his faith. Mar Qardakh was by then governor of Shaqlawa, and in those times he converted to Christianiy before ending up as a martyr in Erbil in 359, for refusing to renounce his faith and turn back to paganism. The tradition also relates that Mar Qardakh came often to visit Raban Boya in his Shaqlawa hermitage.

Another local – and complementary – tradition relates that Raban Boya first settled on the opposite side of the cliff, from where he overlooked his mother’s house. A rocky arch in the mountain could indicate that place. It is only after his mother’s death that he moved and settled his hermitage on the side of the mountain that can be visited nowadays.

The shrine of Raban Boya

At the foot of the cliff, a large fenced religious compound gives access to the shrine of Raban Boya. Right after the gate stands the church of the Virgin Mary, 36°23’50.4”N 44°19’48.8”E and 986 metres high. This church, probably built in 1930, was renovated in 1992 after the creation of the Kurdish no-fly zone, north of the 36thParallel. Mostly funerals are today celebrated in this church, and the deceased persons are buried in the nearby graveyard, backed to the church and which has also been renovated. Let us mention that a Jewish cemetery can also be visited in the Shaqlawa area.

The track that goes up to the shrine from the cliff’s bottom, as well as the metal fence at the entrance of the hermitage date back to the early 21stcentury, thanks to the financial patronage of Sarkis Aghajan, former Christian minister of the Kurdistan Regional Government. In old days, how tough must have been the hiking up to the shrine on a steep and rocky small track! Today, the cobbled path arranged on the first half of the track makes the ascent of visitors and pilgrims much easier, but the second half remains as genuinely rudimentary as in the early times of Christianity in Shaqlawa and of Raban Boya’s ermit life.

Many pilgrims who can’t make it up to the hermitage practise their devotion and rogation in front of a large alcove-shaped cave at the start of the track.

Once at the top and just before really getting into the shrine, there is a 7-to-10-metres deep well, dug in the earth, which was used in old days to collect water running down from the mountain. From the early 2000s, the water is drained through pipe network up to the foot of the cliff and fills a tank close to the bottom cave. And here again, this equipment has been achieved thanks to the funds granted by Sarkis Aghajan.

The shrine itself is still today a poor and ascetic place. The metal staircase and the stone wall built at the entrance of the shrine are the only two concessions to modernity. All the rest and main part of the shrine of Raban Boya is made of small rooms dug in the rock. Right on the left after getting in lies a large rectangular so-called “fertility” stone, polished and sloping, used as a “whishing rock”. Over centuries, many Christian and Muslim women have come sloping down on this stone, face-first and rubbing their stomachs, to have their prayers and wishes to have a baby fulfilled. Indeed, the tradition grants the saint Raban Boya with the miraculous power to make infertile women turn to fertile.

Northwards, the room which is on the far left of the hermitage is, according to the archaeologist Narmen Ali Muhamad Amen, a martyrion[1]supposed to host Raban Boya’s tomb. However this room, situated naturally above the shrine, could as well be a former chapel, as the access is made through what looks like a low and holy door, beyond which stands an altar with steps on top of it, the altar is turned to the East and opened on the vestibule and the two other chambers lining up[2].

For the people from the village[3], the tomb of the saint man is located in the room on the right, backed onto the cliff, under a pile of stones and pebbles.

Raban Boya’s feast day is celebrated there one week after Easter. Spring, both before and after the Resurrection feast day, is an intense period for pilgrimages to the shrine, and this can also be explained by a cool weather and an easier access, allowing pilgrims to picnic at many places on the way.

[1]In « Les églises et monastères du “Kurdistan irakien“à la veille et au lendemain de l’islam ».PhD Thesis by Narmen Ali Muhamad Amen the University of Saint Quentin en Yvelines, under the direction of George Tate and co-directed by Jean-Michel Thierry. May 2001. P.211 and following.

[2]Voir le plan de Narmen Ali Muhmad Amen.

[3]July 15th2017. Testimony by Ninos Hanna, native from Shaqlawa.

Monument's gallery

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute