Mart Shmoni church in Baashiqa

Mart Shmoni church in Baashiqa lies at 36°27’4.08″N 43°20’54.07″E

and 343 metres high.

The original date of the first construction of Mart Shmoni church remains unknown. It has been rebuilt in 1890. Its basilica-styled 3-naves structure is typical of Syriac-Orthodox religious architecture. The magnificent marble royal doors make a very large semi-circular arch with several niches and windows. The church has been profaned by ISIS fighters during the town’s occupation, though causing quite minor damages.

Location

The Syriac-Orthodox church of Mart Shmoni in Baashiqa[1]lies at 36°27’4.08″N 43°20’54.07″Eand 343 metres high, 21 km north-east from Mosul, 10 km north from Bartella, 30 km north from Baghdede (Qaraqosh) and 60 km north of the confluence of the Tigris River (on the west) and the Great Zab (on the east).

We are here in the very heart of Mesopotamia, the Syriacs’ plains. This area bears the marks of its both Syriac-Orthodox and Syriac-Catholic denominations. Baashiqa is also one of the largest community centres for Yazidis, on the eastern part of the Tigris River. The city is famous for olive trees, date palms and orange trees growing.

Baashiqa is quite close from the great Syriac-Orthodox Mar Mattai monastery, on the Mount Maqlūb and place of residence of the Maphrian, primate of the Syriac-Orthodox church in Mesopotamia, until 1859. The Syriac-Orthodox church of Mart Shmoni in Baashiqa took full advantage of the spiritual influence of the nearby monastery.

[1]Several spellings are used for the same name of the town. In his work “Assyrie chrétienne”, the Dominican scholar, Jean-Maurice Fiey uses the name « Bā‘šīqa ». The Orientalist and geographer vital Cuinet used « Bahchika ». Amir Harrak, expert in Syriac and Aramaic language and literature and Professor from Toronto University uses the name « Ba‘šīqā ». Professor Christian Lochon, great Arabic-speaking Orientalist writes “Bachiqa”. For this notice, we chose “Baashiqa” in order to emphasize the pronunciation of the double “a”.

Fragments of history

According to the tradition, Christianity entered the Nineveh plain and the city of Baghdede(Qaraqosh) at as early as the end of the 4thcentury or beginning of the 5thcentury. More surely, sources claim for an evangelization at the 7thcentury.

An important Yazidi community lives also in Baashiqa. The Muslim community has also a little mosque.

The geographer Vital Cuinet censed there 3000 inhabitants at the end of the 19th century: 2000 Christians and 1000 Yazidis[1]. During the 20thcentury, there used to be “2566 inhabitants, split as such: 1517 were Yazidis, 258 Muslims, and 791 Christians. Among those last ones, 3/5 was Jacobite [Syriac-Orthodox] and the rest was Syriac-Catholic[2].” At the beginning of the 21stcentury, before ISIS attacked, Baashiqa was a city with 10 000 inhabitants. Yazidis represented 2/3 of the population[3]. An important Yazidi temple with domes can still be seen in Baashiqa, Saih Muhammad ar Radani temple, where a big community celebration takes place each year, on the first Friday of April.

According to the Christian history of the city, a “famous Jacobite school had been created there around 630[4]”. The school hosted up to 3000 pupils, which reveals the great influence of Syriac-Orthodox tradition in this area, centuries before Catholicism entered and settled in.

As consequences of the arrival of Catholic missions in Mesopotamia and of the conversion to Roman Catholicism of a part of the Syriac-Orthodox people in Baashiqa, the churches’ ownerships were shared between those communities according to the following ratio 2/3 (Orthodox) and 1/3 (Catholics). During this “sharing”, Mart Shmoni church remained Syriac-Orthodox, whereas the church of Mart Mariam al Adra[5], very close on the same square, turned Catholic.

The city was attacked by ISIS in December 2015. During ISIS occupation and until it was liberated in November 2016, ISIS fighters profanated, sullied, and wrecked both large churches of the town: the Syriac-Catholic Mart Mariam al Adra, and the Syriac-Orthodox Mar Shmoni.

Since the town has been freed, inhabitants progressively come back and take part in the Syriac and Yazidi renewal in the Nineveh plain and throughout Mesopotamia.

[1]In La Turquie d’Asie, Tome 2, Ernest Leroux éditeur, Paris, 1891.

[2]In Assyrie Chrétienne, JM Fiey, p.461

[3]In Qaraqoche ou la disparition des chrétiens de la plaine de Ninive,Revue de l’Œuvre d’Orient, Christian Lochon, p.137

[4]In Assyrie Chrétienne, JM Fiey, p.462-463

[5]On this web site, see Mart Mariam al Adra church in Baashiqah

Fragments of a hagiography

The hagiography of Mart Shmoni and her seven saint children is very well known throughout all the Christian East in Mesopotamia. The story of this Jewish family is related in chapter 7, from the second Book of the Maccabees. It reveals how the Jewish were persecuted under the reign of the Seleucid king Antiochus IV Epiphanes, because they respected the Laws of God and and already believed in resurrection and eternal life… two centuries before the advent of Christianity.

The seven Maccabees brothers were then “arrested with their mother and forced to eat pork[1]” in order to abjure their faith. All refused and were sentenced to death and killed, one after the other, under their mother’s eyes. The first one was then “horribly tortured, then fried alive in a pan[2](…)”. Despite her great distress, their mother, Mart Shmoni, encouraged them, one after the other, to remain faithful to the Law of God, until the very last, begging him not to fear the torturer and to “be up to your brothers, accept your death, so that I can come and join you all in mercy.”[3]

[1]In La Bible rendue à l’histoire, Jean Potin, éditions Le Club, Juin 2000, p.616

Description of Mart Shmoni church

The originial date of the first construction of Mart Shmoni church remains unknown. It has been rebuilt in 1890, under the protection of the Syriac-Orthodoc patriarch Patrōs III[1].

The entrance through the surrounding wall gives access to a courtyard, on the northern part of which stands the church itself.

Its basilica-styled 3-naves structure is typical of Syriac-Orthodox religious architecture[2].

In its centre and in its length, the building rests on fairly low marble pillars, topped with large arches, above which a barrel vault rises and leads to the choir, the qestrūm, before getting to the sanctuary, theqankē, after passingthrough the royal doors to access the altar, themadebhō.

In the choir, on a one-step higher platform where the altar boys and the clergymen take place during church services, two wooden lecterns called gūdōcan be seen. From this place are done the Bible readings during masses. Only breach of the original typical plan: the lack of tribune or pulpit, the bīm which was in the past in the middle of the nave and from where priests used to sing the Holy Bible or deliver their homilies. On the other hand, the carved wooden lectern on which lays the Gospel book, the gōgūltō (in other terms, the Golgotha) is still standing at the threshold of the royal doors.

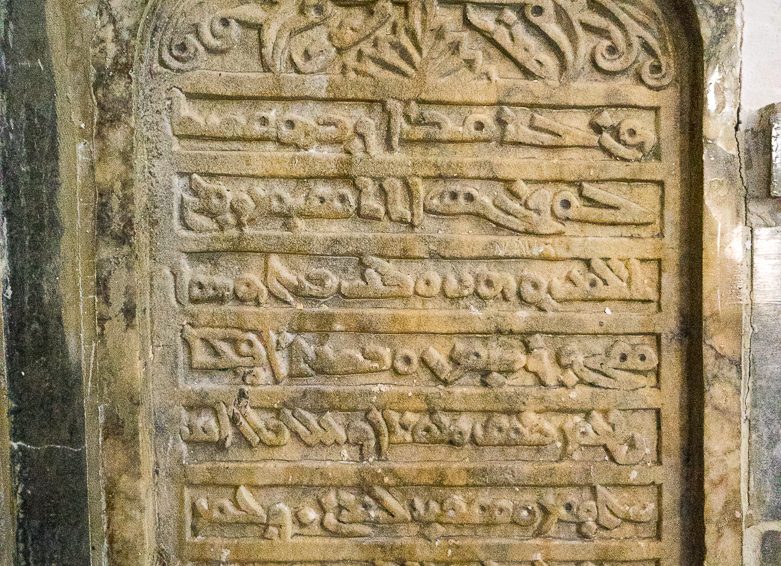

The magnificent marble royal doors consist in a very large semi-circular arch with several niches and windows. The door itself is 3 x 2,4 metres large[3]and is adorned by inscriptions in Syriac language on the pillars and the lintel[4], whereas the reconstruction date is written in Arabic. Under the lintel, a lovely acanthus leaves pattern enhances the brightness of the door.

On each side of the nave, the side aisles lead to side doors. Those doors lead, according to the traditional Syriac-Orthodox architecture, to the martyrium, the bēt sōhdē,on the left, and to the sacristy, bēt diāqōn, and the baptistery, bēt ma’muditō, on the right.

Two beautiful funeral headstones adorned with Syriac and Arabic inscriptions can also be seen at the back of the church, memorials for the priests Gorgis (1871) and Abd al Ahad (1921) whose tombs are situated just underneath[1].

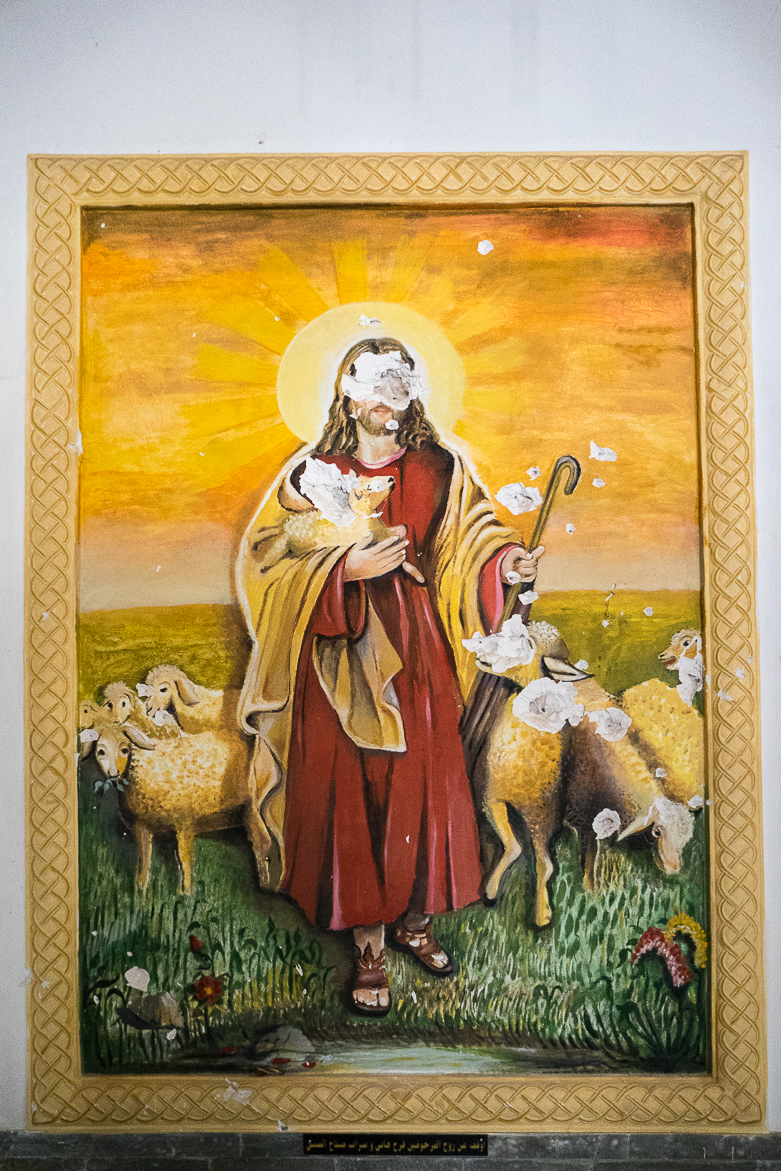

The church has been profaned by ISIS fighters during the town’s occupation, causing quite minor damages though[2].

The altar remains standing. The bullet holes on the concrete parts of the wall can be easily mended. On the contrary, bullet holes on engraved marbles are more difficult to repair, even though they were few. The damaged paintings can be replaced, just like broken windows.

[1]TranslationsInRecueil des inscriptions syriaques, Amir Harrak, Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres, 2017, textes p.372-373 + photos p.170

[2]Church visited on June 17 2017

[1]In Recueil des inscriptions syriaques, Amir Harrak, Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres, 2017, texts p. 370-371 + pictures p.168-169. See also the note A2 concerning Patrōs (Peter) III.

[2]In Les chrétiens de Mossoul et leurs églises pendant la période ottomane de 1516 à 1815. PhD thesis by Bro. Jean-Marie Merigoux, O.P., in 1983, at Aix-en-Provence. P.60 and next.

The author presents in this work the details of typical plans for western Syrian churches (Syriac-Orthodox) and for eastern syrian churches (Church of the East and Chaldean catholic Church)

[3]In Recueil des inscriptions syriaques, Amir Harrak, Académie des inscriptions et belles lettres, 2017, texts p. 370-371 + pictures p.168-169. See also the note A2 concerning Patrōs (Peter) III.

Future prospects for Baashiqa

Trying to rebuild / restore the Syriac-Orthodox, Syriac-Catholic and Yazidi identities and communities in Baashiqa is natural, important, uncertain and brave. Natural, as it catches up with the deep roots of the city and of the country. Important, as it would be a symbol of the defeat of ISIS’ strategy. Uncertain, as the conditions for recovering a fair peace are not yet ready. Brave, because a lot of courage is needed in these circumstances.

Monument's gallery

Monuments

Nearby

Help us preserve the monuments' memory

Family pictures, videos, records, share your documents to make the site live!

I contribute